Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Behind this frightening-looking mask, worn as a disguise by the outlawed Covenanting minister Alexander Peden, lies a fascinating story of rebellion and religious conviction.

Date

1660-1670

Made by

Alexander Peden (1626-1686)

Made from

The mask is made from leather and fabric. The beard and wig are probably made from real human hair. There are also some feathers and false teeth attached.

Dimensions

Length 235 mm, width 260 mm

Museum reference

On display

Kingdom of the Scots, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

The mask was discovered in the 1840s, in a cottage near Cumnock. The mask and wig, along with his sword, had been handed down through his family for generations.

View this detailed video close-up of the mask. It is made from leather and fabric. The beard and wig are probably made from real human hair and there are also some feathers and false teeth attached.

Born in Auchencloich near Sorn, Ayrshire, Alexander Peden grew up in a moderately prosperous family. He went to school in nearby Mauchline and attended Glasgow University between 1643 and 1648. Before entering the ministry, he is thought to have served as a schoolmaster or family tutor in different places. In 1659 Peden was ordained and became minister at New Luce in Wigtownshire, where he served until 1662, when he was ejected for refusing to conform to the Episcopalian church practices.

Peden became what today we might refer to as a ‘celebrity’ or charismatic preacher and he wore this mask as a disguise to avoid arrest for preaching illegally. He was bitterly opposed to the religious changes imposed by Charles II and encouraged his followers to defy them. Most of his preaching was done in the south and west of Scotland. When not preaching he would travel between sites, sleeping in caves and shelters to avoid recognition and capture.

Side view of Alexander Peden's mask disguise.

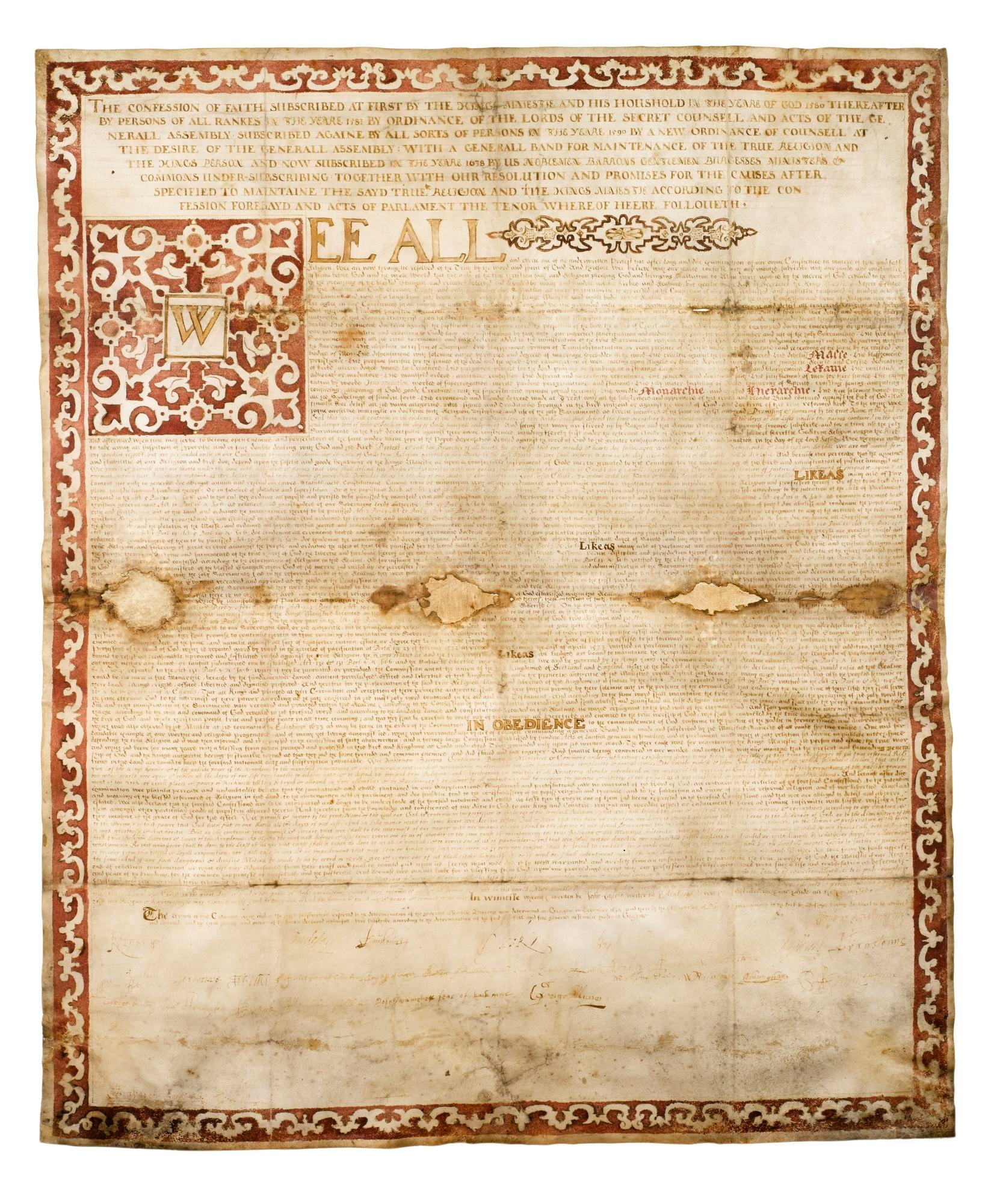

‘Covenanter’ was the name given to the people of Scotland who signed the National Covenant, in opposition to attempted religious changes to the Scottish Presbyterian kirk by Charles I. People in each parish signed their copy of this historic document, and several of these covenants are on display the National Museum of Scotland, just a few yards away from Greyfriars Kirk, where it was first signed on 28 February 1638.

The Signing of the National Covenant in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh by William Allan. Credit: Museums & Galleries Edinburgh.

Presbyterianism is a version of Protestantism with its own particular doctrine and religious worship, and it is the form that the Scottish kirk took after the Reformation in 1560. This was done in defiance of the Scottish monarch at the time, Mary, Queen of Scots. Subsequently, the issue of who determined religious policy continued to be a source of conflict between the Scottish crown and the Presbyterian body of the kirk for over a century.

In 1638, Charles tried to introduce the English prayer book into the Scottish kirk, and this was fiercely resisted. The resulting Covenant was a pledge or contract between the Scottish people and God to uphold Presbyterian values. This included the refusal to accept the King as the spiritual head of the church in Scotland and rejected his interference in it.

The Covenant also rejected the hierarchical nature of the Episcopalian system of church government, which was ruled by bishops, who Presbyterians felt were controlled by the king. Instead Presbyterians believed that everyone in the kirk was equal, and that it therefore should be governed by the national General Assembly, and the regional presbyteries, a church court combining ministers with church elders selected from each parish. Most importantly Presbyterians believed that ministers should be chosen by their congregations. The difference between Presbyterianism and Episcopalianism was thus essentially a heated dispute over two opposing forms of Protestantism.

For Charles I, Presbyterian opposition represented a rejection of his personal authority in the kirk, and was therefore treasonous, and he declared war on the Covenanters. This war would bring about his downfall: in need of funds to pursue the war, Charles was forced to recall the English Parliament after almost 10 years of ruling alone. The subsequent deadlock between King and Parliament resulted in civil war across England, Scotland and Ireland, and Charles I’s execution in 1649.

The National Covenant in Kingdom of the Scots at National Museum of Scotland.

In 1660, Charles II was restored to the throne. In return for assistance from the Covenanters, he had reluctantly signed the Covenant. Yet in 1662 the new King renounced his promise and declared himself the head of the Scottish kirk, re-introducing Episcopalian practices.

A period of persecution followed, in which some 350 ministers with Covenanting sympathies were forced from their churches. Rather than suffer the imposition of the hierarchy of the Episcopalian system, they became outlaws, continuing to fight their cause.

'The Marriage of the Covenanter' by Alexander Johnston from Glasgow Museums showing an open air ceremony.

Many began preaching illegally at open air services known as ‘coventicles’ – a practice that became punishable by death under Charles’s new laws. Covenanters were hunted down by government troops, imprisoned, executed or transported to the colonies. All Scots were forced to take an oath renouncing the Covenant. Anybody who refused to do so risked their lives, and many chose to die rather than renounce their beliefs. This bloody period became known as ‘the Killing Time’.

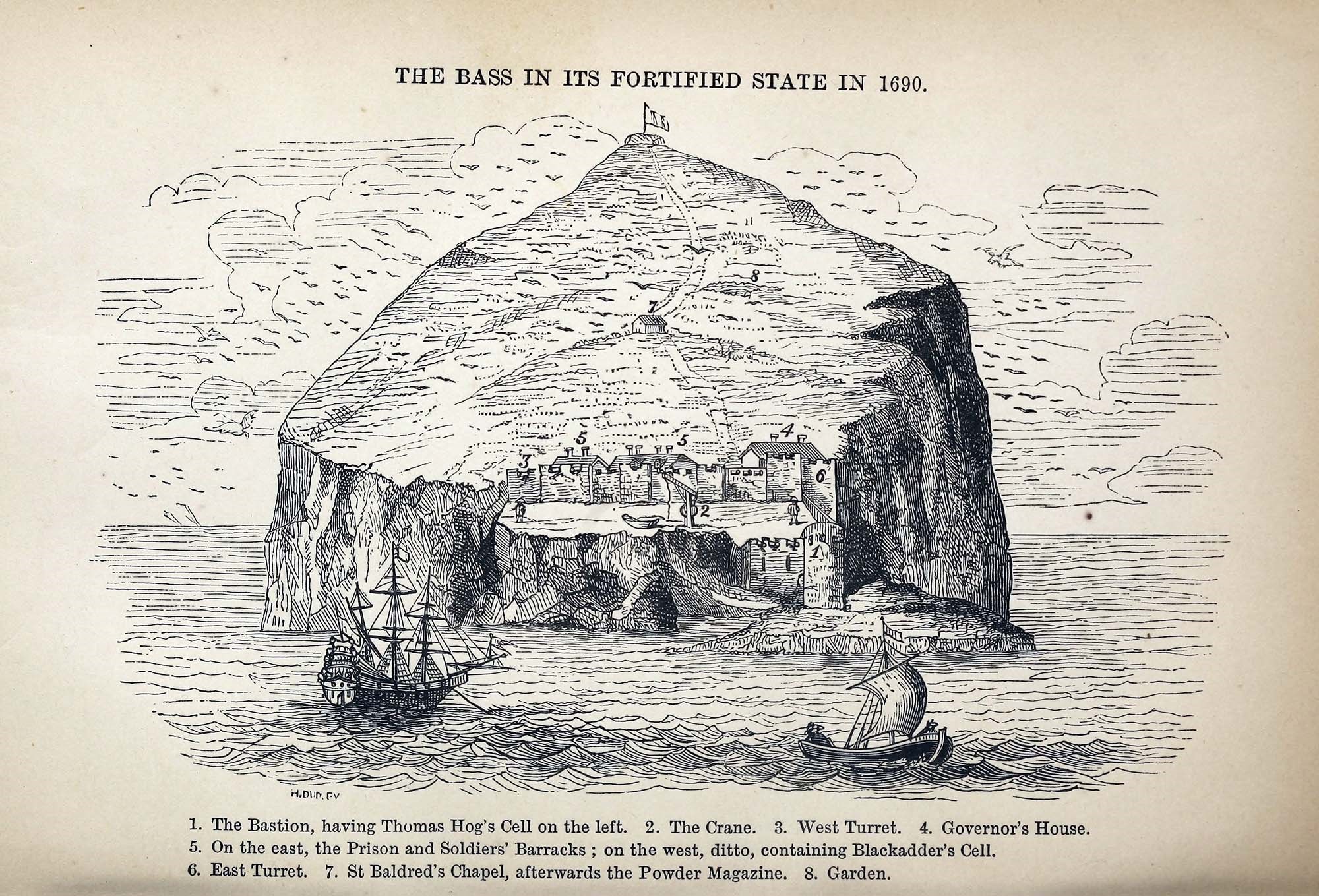

The Bass Rock from North Berwick by Honge / CC BY-SA

After 11 years on the run as an outlaw, Alexander Peden was captured and imprisoned for four years on the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth – the Scottish Alcatraz. Yet plans to exile him to a plantation in Virginia in America backfired when a sympathetic English captain allowed him to jump ship, and he escaped to Ireland. He then returned to Scotland, where he continued to preach illegally throughout the Killing Times risking his own life and those of his followers. Prematurely aged and debilitated, he found shelter in a cave on the banks of Ayr near Sorn. His final days before his were death were spent at this brother’s house at Auchinleck, where he died on 28 January 1686, and was buried in Auchinleck church.

Image from "The Bass Rock - Its Civil and Ecclesiastical History, Geology, Martyrology, Zoology and Botany", published at Edinburgh in 1847.

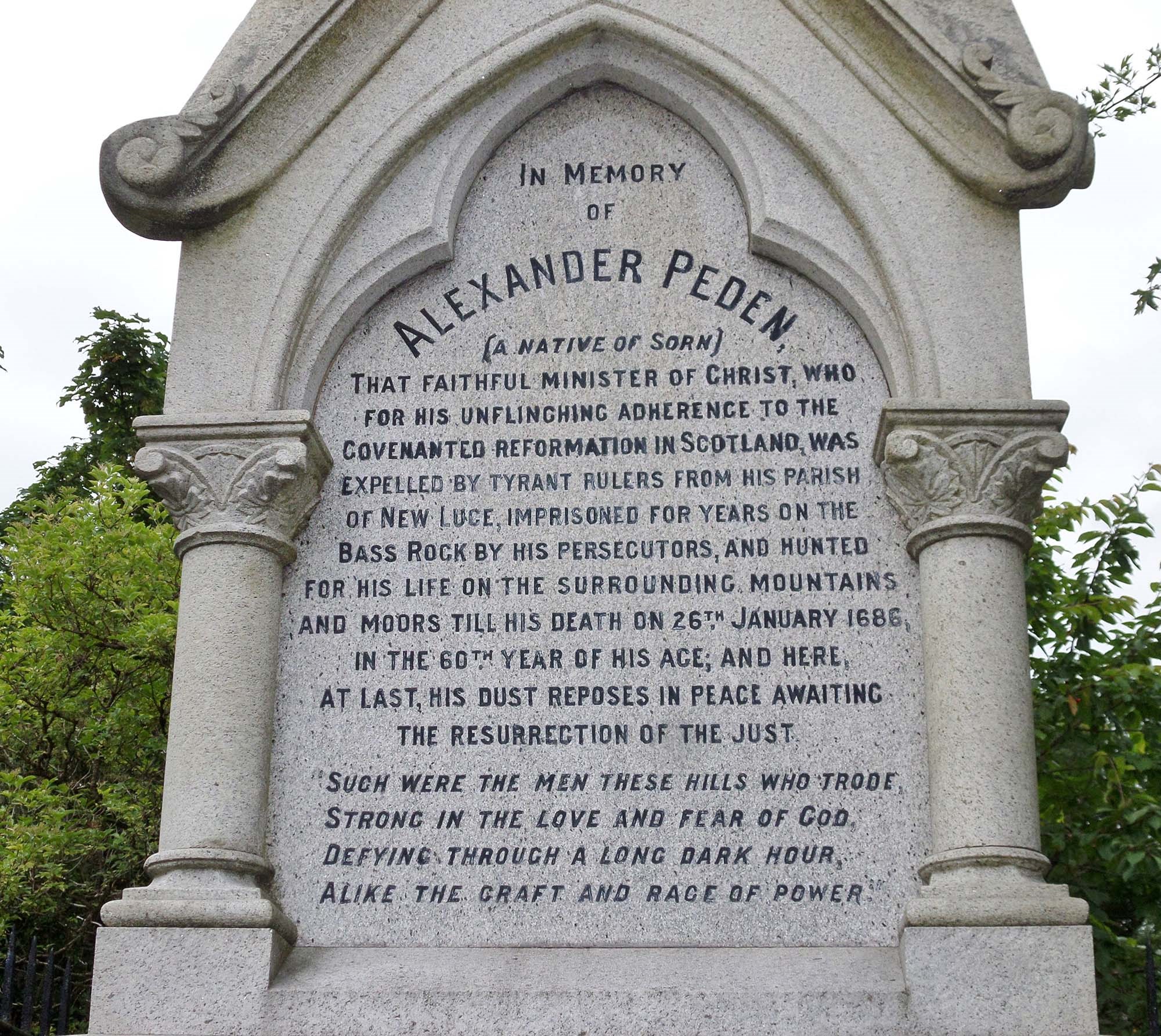

Alexander Peden’s remains were dug up by vengeful government troops six weeks after he was buried. Since they had failed to hang him, he was reburied by the troops at the foot of gallows in Cumnock. The local community adopted the spot as their burial-ground out of reverence for Peden. South and central Scotland is dotted with sites honouring Peden’s memory – Peden’s Pulpit and Peden’s Stone continue into the 21st century to be sites of commemorative services.

Peden stone Harthill Shotts, near the modern Alexander Peden Primary School Public. In the public domain.

Peden's pulpit in the Linn Glen, Dalry which overlooks a natural amphitheatre by Rosser1954 / Public domain

Alexander Peden Memorial inscription, Cumnock, East Ayrshire, Scotland. By Rosser1954 / CC BY-SA