Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Scotland Creates volunteer Aileen Miller explains why this pioneering Edinburgh Modular Arm System (EMAS) is so awesome.

Date

Late 1990s

Made in

Edinburgh, Scotland

Made by

David Gow

Made from

Metal and plastic

Acquired

Gifted by NHS Lothian and David Gow

Museum reference

On display

Technology by Design, Level 3, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

Campbell Aird appeared in the Guinness Book of Records as the ‘man with the most successful false arm.’

When we first cast eyes on this bionic arm thing for our exhibition; it had me purely because it looks awesome. I mean, it looks like Robocop in a Franz Ferdinand video plus it was designed in Edinburgh. Sorted!

It didn’t take much research to realise the significance of the EMAS (Edinburgh Modular Arm System) not only within the scientific community but also in the advances that its development has led to.

Centuries ago, it wasn’t totally unheard of to lose a limb. In fact, if you were a knight, it wasn’t totally unheard of for you to stick an iron arm on and gallop back onto the battlefield, although these ‘fighting hands’ were reserved for the few who could afford them.

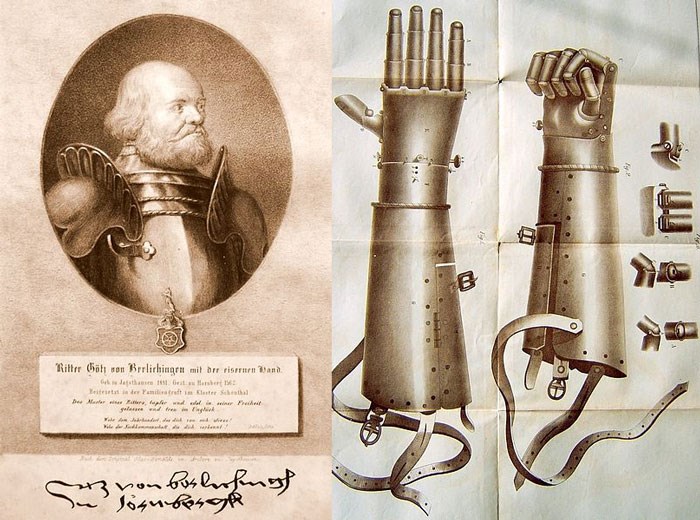

Götz von Berlichingen, a German mercenary was one such wealthy individual. He lost his arm in battle and had a replacement made of iron. The replacement featured a complex system of springs and ratchets, which allowed Berlichingen to continue doing the things he loved, such as grasp a sword and hold his own hand in a card game. Well, he had his priorities.

Above: Götz von Berlichingen and a drawing of his iron hand.

The hand is now on display at Jagsthausen Castle as an example of the beginnings of modern prosthetics. However, despite Berlichingen’s innovative extremity, it wasn’t until the end of the Middle Ages that more functional prosthetics began to appear and a further 450 years before the kind of prosthetics we would recognise today.

The Princess Margaret Rose Hospital in Edinburgh, had been developing pneumatic powered prosthetics for children since 1963, but it wasn’t until David Gow took control in 1986 that the work was assimilated into the development of electrical arm prosthetics.

Gow believed that the pneumatic design was not user-friendly, especially for the children they were originally intended for, describing them as “…inconvenient and cumbersome… [with] limitations in functionality.” He and his team set out to create a system that was not only lighter and more convenient for the user but that had component parts that could be used in prosthesis for varying aged and sized patients.

In June 1988 at the First International Workshop of Rehabilitation Robotics in Ottawa, Canada it was officially announced that work on the world’s first modular arm system had begun.

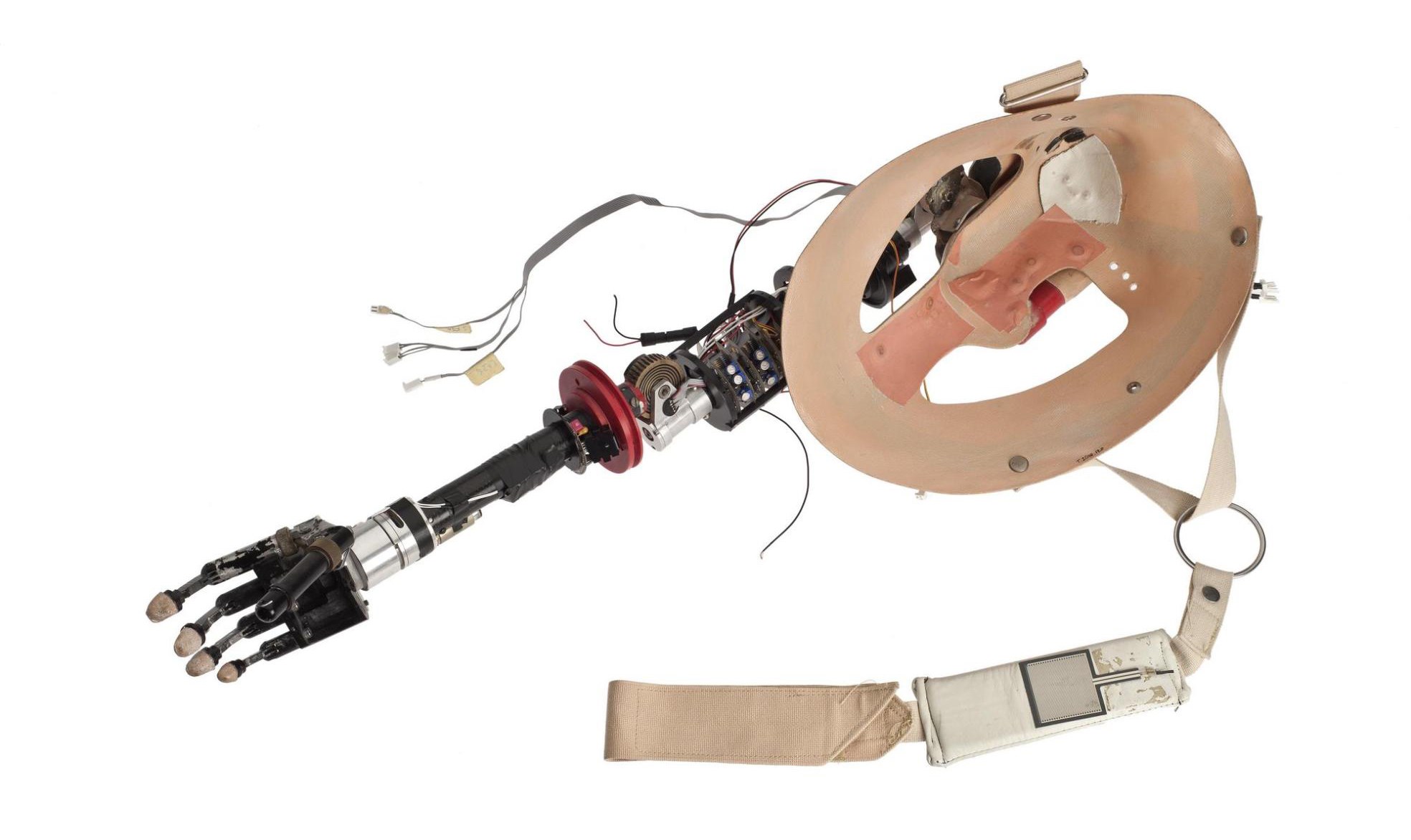

In August 1998 the world’s first bionic arm was fitted to Campbell Aird at the Princess Margaret Rose Hospital. The arm, the first to have a powered shoulder, elbow, wrist and fingers, was controlled by electronic micro-sensors (and presumably a bit of witchcraft) that sent pulses to the arm. At 1.8kg, the metal and plastic creation was lighter than a natural arm and much easier to use than the pneumatic ones that preceded it. Aird used the EMAS for 18 months after the initial fitting, continuing to work regularly with the team on adapting the EMAS for everyday use.

Above: The Edinburgh Modular Arm System worn by Campbell Aird.

Aird lost his arm to muscular cancer in 1982 at the age of 31 and decided that the whole taking things easy route wasn’t for him, so agreed to take part in the EMAS project. Though there were initial teething problems to resolve when the arm was first fitted, such as the arm sticking in the upright position, making for a bit of an awkward shopping trip one day. However, the issues were resolved, and fast.

Aird appeared in documentaries about his bionic arm, praising Gow and the team for their pioneering work and the way it changed his life. He commented "For the first time in 16 years I recently reached above my head to pick a book off a shelf. It was a great moment for me." Though not content with being able to reach the top shelf, he learned to fly in 1999 (although admittedly not using the EMAS). Oh, and he also went on to win 14 Clay Pigeon Shooting Trophies and raised money for several charities. He windsurfed across the Forth and the English Channel once. Seriously. This guy.

The EMAS, and the work that Aird did with it, led to Gow forming a spin-out company from the NHS in 2002, and from there he went on to launch the i-limb hand in 2007, the first prosthetic hand to have individually powered articulating fingers. If this technology keeps advancing this fast, years from now those creeping Halloween hands you get are going to be seriously amazing.

The EMAS opened the doors for Gow and the wider world of prosthetics to the exciting possibilities of Rehabilitation Engineering and led to developments that are advancing every day and could have positive implications for thousands of people.

So yeah, it’s pretty awesome.

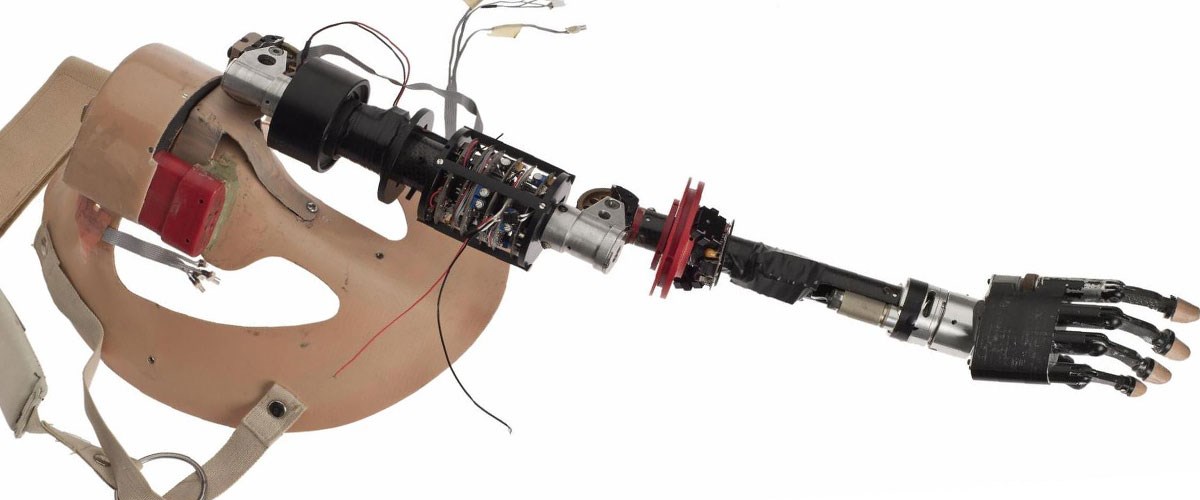

Above: The EMAS bionic arm with the first generation i-limb.

Above: the i-limb ultra from Touch Bionics. Image © Touch Bionics.