Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

These rare Jacobite and British military colours were carried into battle at Culloden by opposing sides, but they now hang together in the National Museum of Scotland as evidence of a contentious and divisive episode from Scotland’s past.

Date

1746

On display

Scotland Transformed, Level 3, National Museum of Scotland

Acquired by

Given by the Stewart Society

Museum reference

On display

Scotland Transformed, Level 3, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

The Battle of Culloden was the last major battle fought on British soil.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart landed in Scotland in 1745, in an attempt to regain the crown for his exiled father, James Frances Edward Stuart.

His rebellion was crushed on 16 April 1746, when Jacobite forces met the government army, commanded by William, Duke of Cumberland, at Culloden near Inverness. In a brief but bloody battle, the Jacobites were driven from the field, their cause at an end.

Above: Engraved map showing a plan of the Battle of Culloden and the adjacent country, attributed to John Finlayson, Edinburgh, dated 1746. On display in the Scotland Transformed gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

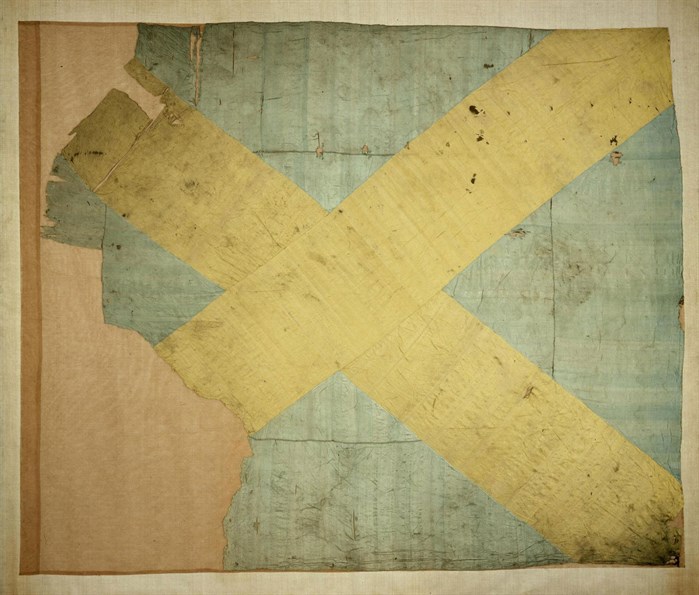

Above: Appin Stewart colour carried at Culloden, 1746.

This rare Jacobite colour, or flag, was carried by the Appin Stewart Regiment at the Battle of Culloden, a battle which saw the defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobite cause.

The Stewarts of Appin were one of the first clans to come out in support of Prince Charles Edward. At Culloden the clan regiment was on the right of the Jacobite front.

According to accounts of the battle, 17 clansmen fell while carrying the colour. In the chaos of the Jacobite defeat, the bloodstained flag was ripped from its pole by Donald Livingstone, a soldier of the regiment. He managed to escape with the colour wrapped round his body beneath his clothes. He smuggled it from the field of battle, and later gave it to the father of his superior officer, Alexander Stewart of Ballachulish, who had been killed at Culloden.

By rescuing the colour, at great personal risk, Donald Livingstone saved it from the fate of nearly all the other colours of the Jacobite army. The government saw them as symbols of rebellion rather than legitimate trophies of war, and the captured colours were ceremonially burnt at Edinburgh’s Mercat Cross by the public executioner.

The Jacobite flag is displayed in the National Museum of Scotland opposite the King’s colour of the Barrell’s Regiment. At this time, regiments in the British army were known by the name of their colonel, in this case William Barrell. At Culloden, Barrell’s was on the extreme left of the government front line and the regiment bore the full brunt of the Jacobite charge, which included the Stewarts of Appin. Consequently Barrell’s Regiment suffered the heaviest casualties of any government unit.

Above: King’s colour of Barrell’s Regiment.

The battle was depicted by military artist David Morier in his famous painting ‘An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745’.

Above: An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745 c. 1745-85. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017. You can find out more about the painting on the Royal Collection website.

Early in the 19th century, colours of Barrell’s Regiment were acquired by David Stewart of Garth, a noted historian of the highlands and friend of Sir Walter Scott. In a gesture typical of the attitude of many contemporary Scots towards the Jacobite cause, Stewart of Garth presented them to Stewart of Ballachulish, the custodian of the Appin colour, so that, in Garth’s words ‘the flags which were opposed to each other at Culloden might thereafter rest in peace side by side.’

Although Stewart of Garth was conspicuously Highland, he was also an ex-British army officer and strong supporter of the Hanoverian dynasty. As a member of Scott’s inner circle he helped to plan the visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822. For him, the ’45 was a civil war, in both a Scottish and a British context and he was sympathetic to those who had fought and lost in the Jacobite cause. His gesture of reconciliation between former foes was intended to help heal the divisions of the past.

Header image: Barrell's Regimental colour carried at Culloden.