Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

National Museums Scotland’s ancient Egyptian coffin collection remains largely unknown and has many exceptional items.

The Egyptians hoped to be able to continue to enjoy their lives, even after death, through their belief in an afterlife. To ensure this happened, a person needed to be given a proper burial and provided with food, drink and other provisions for the afterlife. Wealthy individuals sought to ensure their survival for eternity by having their body preserved through the process of mummification and their likeness and name preserved through monuments like statues and decorated tomb chapels. Funerary beliefs and practices did not stay the same however; they changed over thousands of years of Egyptian history. Explore this evolution through highlights from our collection of coffins, mummy masks and grave goods here.

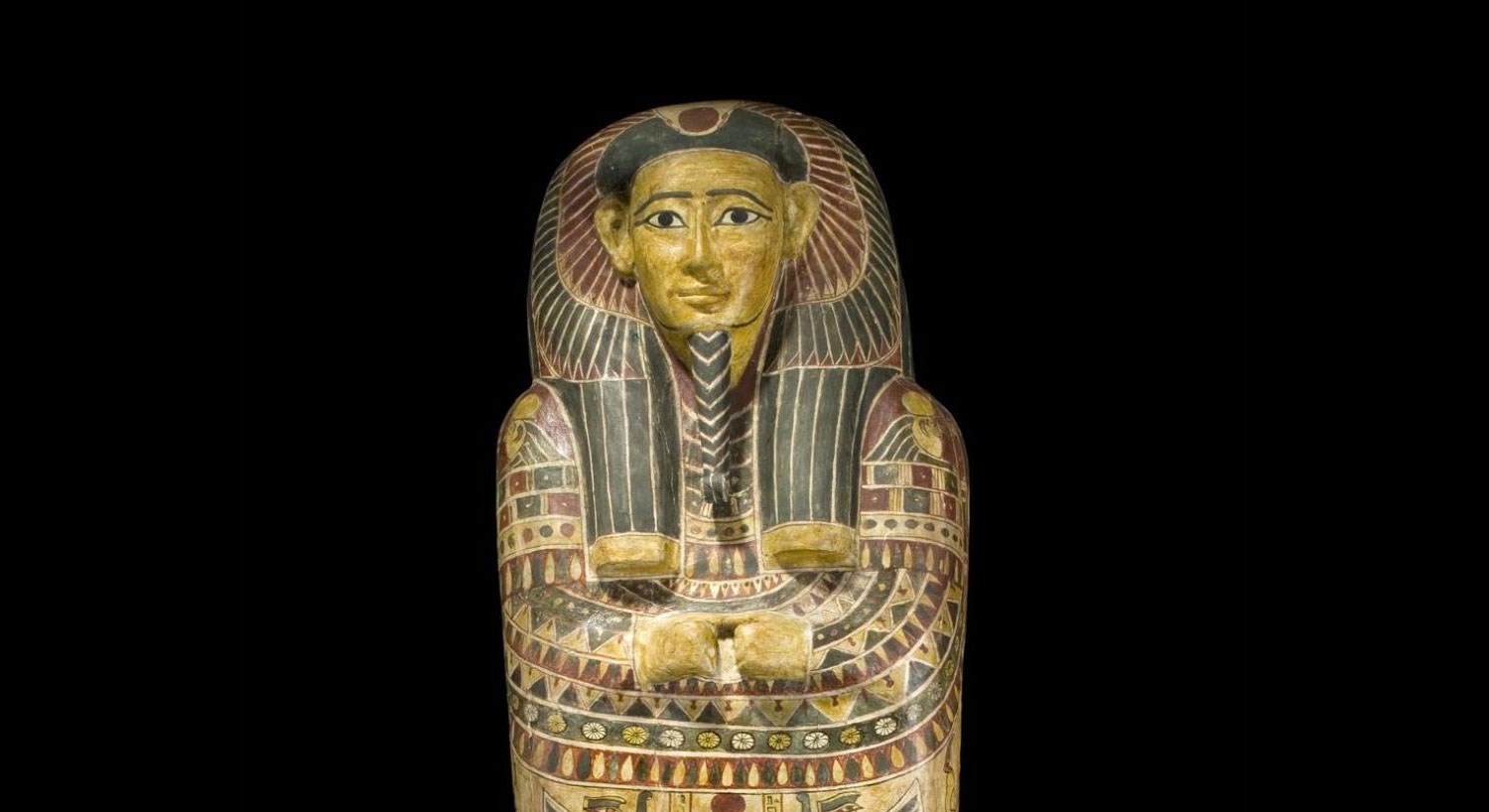

In the Third Intermediate Period, the burials of the wealthy replaced the innermost coffin with a mummy-case made of cartonnage (linen and plaster), brightly painted with images of protective symbols, gods, and goddesses.

The face on the coffin of the priest Nehemsumut is painted pink and surrounded by a black wig with narrow yellow stripes, which hide the ears. The top of the head has a scarab (beetle) outlined in white on a black background. Around the temples are three rows; the upper one solid red, the second painted to imitate gold with inlays of red and green and the last represented with white flower petals.

A broad collar is shown around the upper part of the torso, depicted in red and white, with blue, green and black directly below the throat. Directly below the collar is a ram-headed vulture with a sun disc on its head and wings spreading almost to the shoulders.

The left part of the foot-case is decorated with a standing jackal (wild dog), with religious symbols either side.

On display: Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

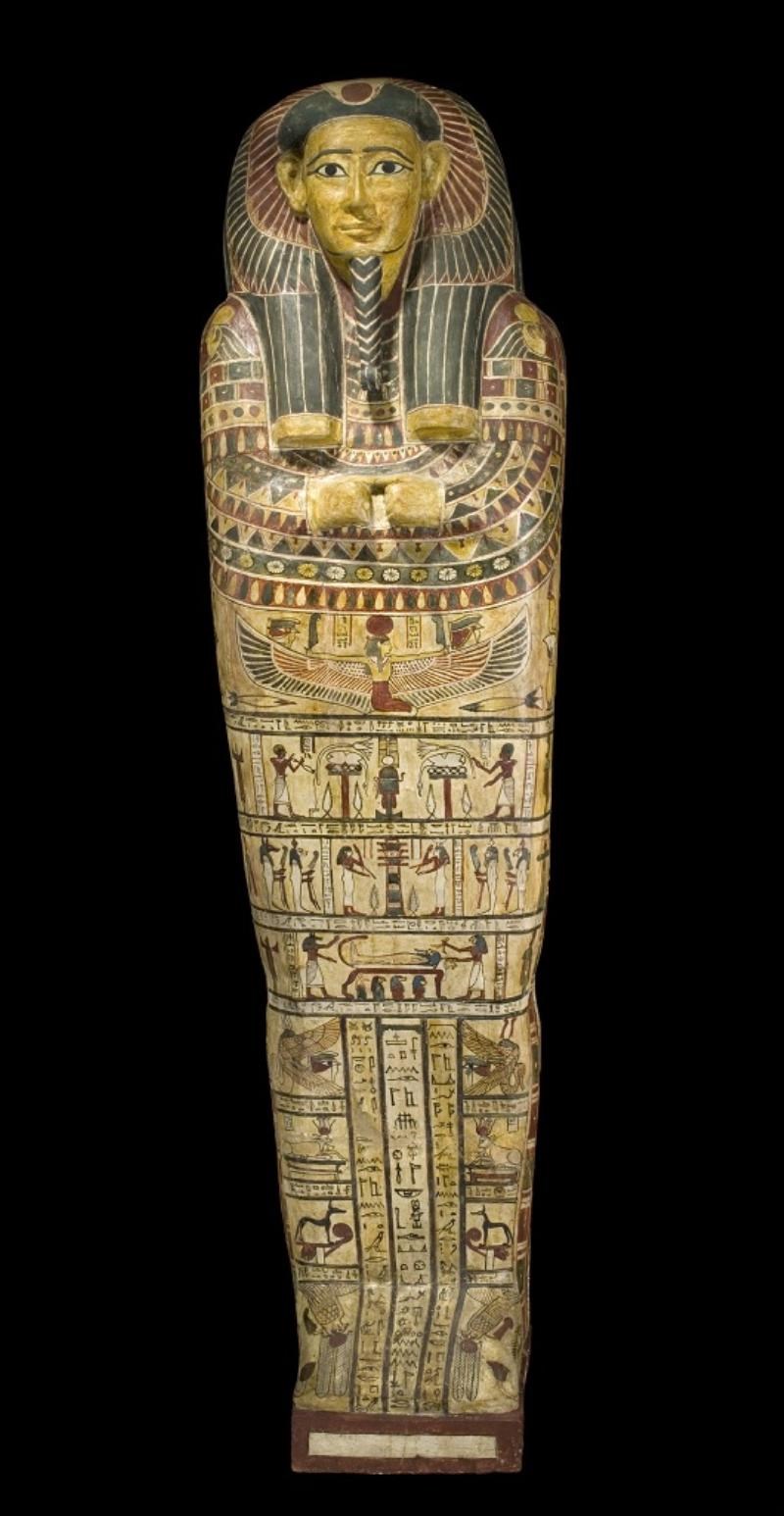

Khnumhotep was an estate overseer who lived around 1940-1760 BC. His is one of the earliest coffins in our collection, dating to the Middle Kingdom (c.2055-1795 BC). Up until this period, coffins had typically been rectangular in shape. But the coffin of Khnumhotep is an innovative new form, which was shaped to look like the deceased person.

The coffin represents Khnumhotep wrapped in white linen wrappings with gold skin, evoking the Egyptian belief that the skin of the gods was made of gold. By depicting him this way, the coffin magically transformed Khnumhotep to help him reach the afterlife.

The coffin is painted white, with four gold bands with black edging encircling the lid and base. The lid shows a man with a black-painted wig, gilded face, black-painted eyebrows and inlaid-stone eyes. A false beard is attached to the chin, with gold paint to indicate texture and a black-painted strap at the sides of the face. He wears a collar painted with 13 concentric bands of black, red or green separated by narrow white lines, and an outer band showing pairs of green or red drop-beads on a gold base with a green border.

At the centre on the front of the lid is a column of gold hieroglyphs on a green background, which runs from the bottom of the collar to the lowest band at the ankles. The interior of the lid and base are painted white but the left sides have been discoloured to dark brown by oils associated with the mummification process.

On display: Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

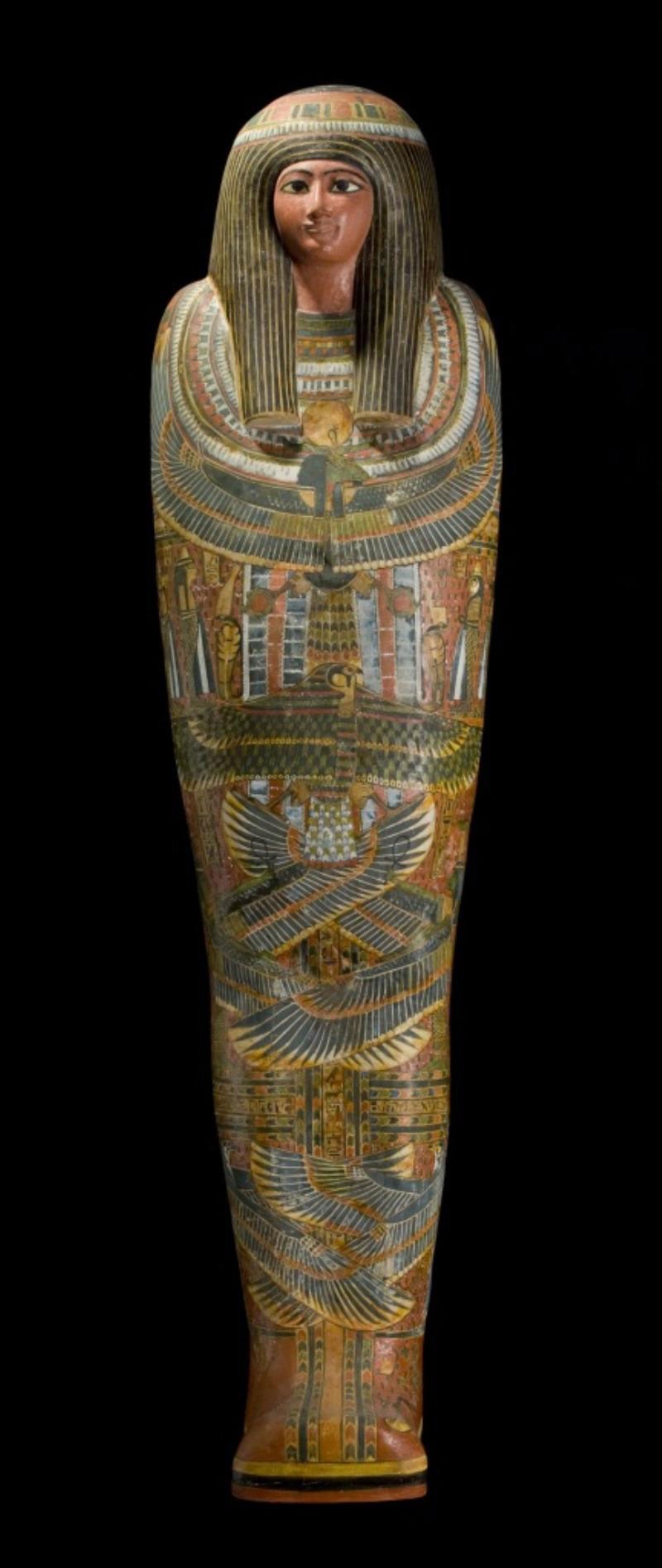

This coffin lid was donated to the museum along with the coffin base of the priest Iufenamun and dates to the same period, but it belonged to a priestess of Amun called Tjentwerethequa, thought perhaps to have been Iufenamun’s grandmother.

This coffin lid is human-shaped, decorated with a multi-coloured scheme based on red on a yellow background, with red, green and blue-green pigment and a yellow varnish. The deceased is shown wearing a wig covering the ears and the face is painted yellow. Directly below, the breasts are decorated with multi-coloured rosettes.

A broad collar with hawk-headed ends covers much of the upper torso, with different types of decoration placed on top. There is a pair of crossed arms with heavily ornamented bracelets on each. The hands are painted yellow with red, green and blue stars.

Four bands of text run across the lid and along the edges of the toes to the edge of the lid, while a further pair of bands run vertically from the toes along the top of the feet.

Underneath the feet is a figure of the goddess Nephthys kneeling on a gold-sign. An ankh (symbolising life) hangs from each outstretched arm, with the sky-sign above her and symbols of the 'west' on either side.

On display: Discoveries, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland

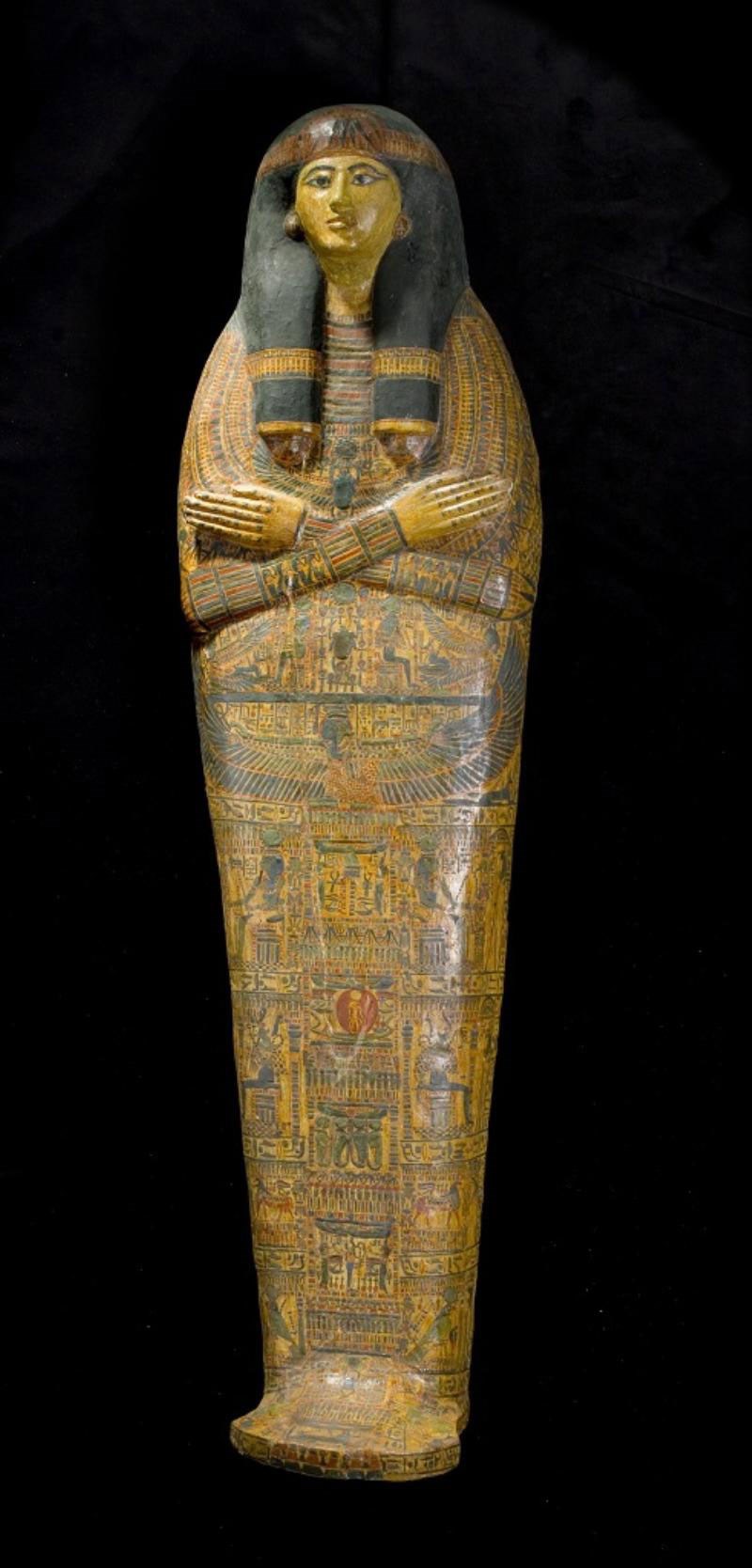

Coffins such as this did not provide a realistic portrait of the dead person, but rather they projected an idealised image of what they wished to look like for eternity. The plaited false beard Irthorru wears was associated with the god Osiris, who was the first person to be mummified and reborn into the afterlife. This beard, along with other symbols of rebirth such as the sun and scarab beetle, would have been intended to help Irthorru’s resurrection after death.

His is painted yellow, with white eyes and a black and a green-striped beard. The top of the head has a red-outlined winged scarab (beetle) pushing a red sun-disc that lies directly above the brow. The wings of the scarab reach down the wig on either side of the face and the upper row of feathers is red and the lower row is green.

A painted collar begins at the upper-arm level and is painted in red and green on a cream ground. It has a dominant triangular pattern ending in a row of alternate yellow and red rosettes and then a row of drop-pendants in green and cream. The hands emerge from the collar and painted yellow.

The sides of the coffin base and lid are decorated with a large cobra with its hood painted in green, stretching down the whole side of the coffin to the feet. It is enclosed by white-bordered bands alternating green and red, with a white central dot, and separated by narrow white and red bars.

The wig on the base is a solid green and is decorated on the underside with a standing winged goddess, with a red sun-disc on her head and a feather in each hand.

The dominant decorative scheme is a red and green criss-cross motif on a white ground decorated by a central column of text, enclosed by red and green bands.

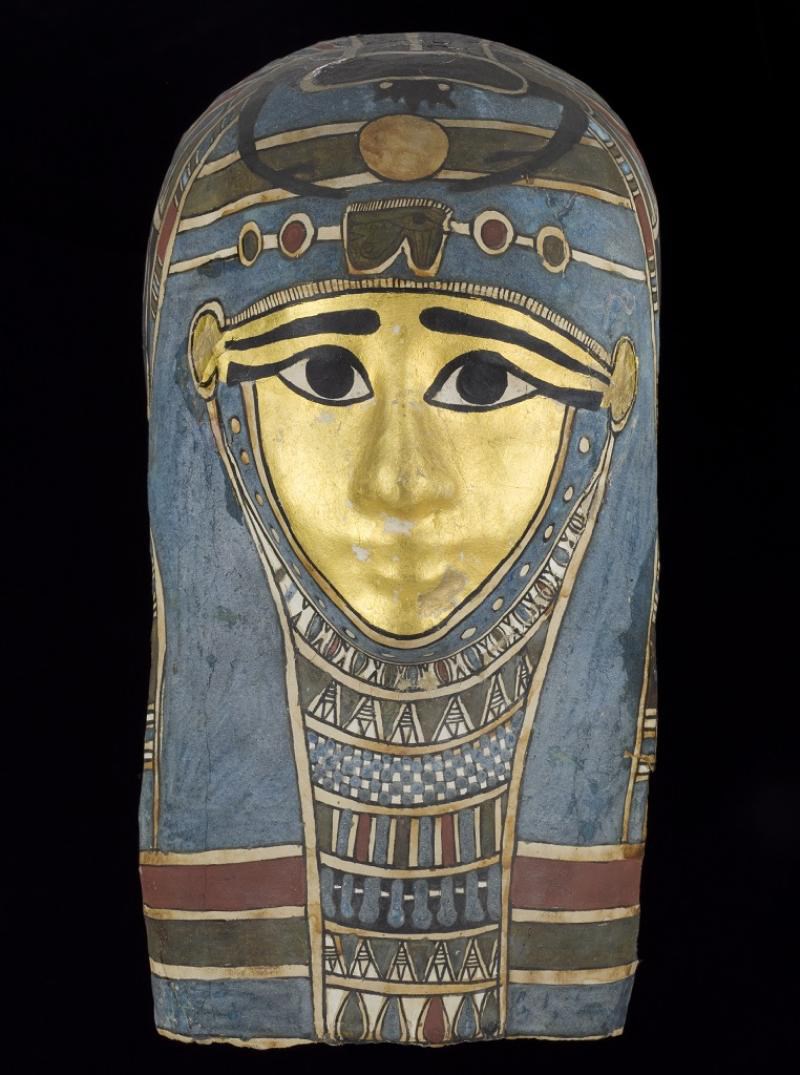

During the Ptolemaic period (323-30 BC), following conquest by Alexander the Great, Egypt was ruled by one of Alexander's generals, Ptolemy I Soter, and his successors, until the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest. During this period, the use of mummy masks became increasingly common. A mummy mask served as protection but could also act as a substitute for the mummified head should it be damaged or lost.

This mummy mask shows the deceased wearing a wig and collar. The mask has a blue strip with yellow discs running from just beneath the rear parts of the eyes to the chin, covering parts of the cheeks. The face elsewhere and the very small high-set ears are gilded. The majority of the wig is blue with a white band with green and red discs along the brow.

A large black scarab (beetle) dominates the top of the head, with multi-coloured wings reaching down to the shoulders of the mask. The wings of the scarab divide the mask in two, the front half painted green, the rear red, with a white tie at the back and the curl block in red. The lower part of the rear of the mask is also red. Most areas of colour are outlined in white.

On display: Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

You can explore the mask in more detail below.

Under Roman rule, funerary customs in Egypt changed even more rapidly and began to incorporate influences from Classical art. This unique double-coffin was used to bury two young half-brothers. The interior of coffins often depicted an image of the sky-goddess Nut, who was thought to protect the deceased. This coffin has two images of the goddess, one for each child. In Egypt, it was only following the introduction of Christianity that the process of mummification finally began to die out.

The mummified bodies of these boys were prepared with the utmost care and elaborately wrapped, indicating high status in their society. It is not known why the boys died so young, but we know from papyrus left with the mummified bodies that they had the same father but different mothers. The boys' death highlights a sad aspect of the ancient world where young children were very likely to die. Tragedies, such as disease devastating a whole family, were all too frequent.

On display: Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland