Galloway Hoard: Viking-age Treasure

19 February to 9 May 2021, National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh (and touring thereafter)

#GallowayHoard

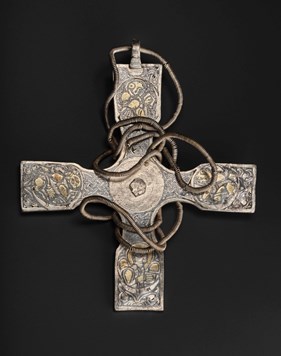

Previously encrusted in a millennium’s worth of dirt, months of painstaking cleaning and conservation work has revealed an intricately decorated silver cross, allowing scholars to view this detail for the first time before it is put on public display in a new exhibition, Galloway Hoard: Viking-age Treasure at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh (19 Feb – 9 May 2021).

The silver pectoral cross pre-conservation

The silver cross is decorated in Late Anglo-Saxon style using black niello and gold-leaf. In each of the four arms of the cross are the symbols of the four evangelists who wrote the Gospels of the New Testament, Saint Matthew, Mark (Lion), Luke (Cow) and John (Eagle).

Dr Martin Goldberg, Principal Curator of Early Medieval and Viking collections said,

“Our approach to developing further understanding of the Galloway Hoard involves the great patience, careful examination and pain-staking care of conservation, combined with wide-ranging research on the great variety of materials and objects in this outstanding hoard. The cross is a wonderfully visual representation of the work we have been doing to reveal new details about the Galloway Hoard. The conservation work lets us see this object clearly for the first time in over a thousand years, but it also reveals a whole new set of questions.

Silver bullion, hacksilver and ingots, formed the upper parcel of the Galloway Hoard, but there was also this very unusual feature – a cross with a fine spiral chain – recently worn, but damaged. This one object poses many of the questions that we often start with when we are talking about the Viking Age. Was it bullion too, destined to be melted down into the types of ingots it was found with? We can easily imagine this cross being robbed from a Christian cleric during a raid on a church - a classic stereotype of the Viking Age. But the complexity of this hoard forces us to reconsider simple stereotypes.

The cross is just one of many unusual features in the Galloway Hoard. Late Anglo-Saxon Christian metalwork is very unusual in Viking-age silver hoards. As well as silver bullion, the Galloway Hoard contains a large collection of brooches, bracelets, glass beads, pendants, curios, heirlooms and more gold than any other hoard surviving from Viking-age Britain and Ireland, as well as outstanding preservation of organic materials including Scotland’s earliest examples of silk.

Answers to the questions about the motives for burial can only be attempted once every object in the Hoard is analysed and understood, along with investigation of the wider context. This work will continue for years.”

Dr Leslie Webster, former Keeper of Britain, Prehistory and Europe at the British Museum, said:

“The pectoral cross, with its subtle decoration of evangelist symbols and foliage, glittering gold and black inlays, and its delicately coiled chain, is an outstanding example of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmith’s art. It was made in Northumbria in the later ninth century for a high-ranking cleric, as the distinctive form of the cross suggests. Anglo-Saxon crosses of this kind are exceptionally rare, and only one other – much less elaborate – is known from the ninth century. The discovery of this pendant cross, in such a remarkable context, is of major importance for the study of early medieval goldsmith’s work, and for our understanding of Viking and Anglo-Saxon interactions in this turbulent period.”

The Galloway Hoard brings together the richest collection of rare and unique Viking-age objects ever found in Britain or Ireland. Buried around the end of the 9th century, the Hoard brings together a stunning variety of objects and materials in one discovery.

The Hoard was buried in four distinct parcels. The cross was buried in the top layer with a parcel of silver bullion. This was separated from a lower layer of three parts: firstly another parcel of silver bullion wrapped in leather and twice as big as the one above; secondly a cluster of four elaborately decorated silver ‘ribbon’ arm-rings bound together and concealing in their midst a small wooden box containing three items of gold; and thirdly a lidded, silver gilt vessel wrapped in layers of textile and packed full of carefully wrapped beads, pendants, brooches, curios, relics and heirlooms. Research and conservation continues into these rare surviving organic materials and the inorganic objects they are combined with.

Discovering and decoding the secrets of the Galloway Hoard is a multi-layered process. Conservation of the metal objects has revealed decorations, inscriptions and other details that were not previously visible. But even the act of removing dirt to see what’s underneath is not as simple as it might appear. The silver spiral chain wrapped around the cross was particularly intricate, made from wire less than a millimetre in diameter and wrapped around an organic core, preserved within the coiled silver and identified as animal gut. Conservators improvised a cleaning tool by carving a porcupine quill, sharp enough to remove the dirt yet soft enough not to damage the metalwork.

The pectoral cross post-conservation

It is this combination of organic and inorganic materials that provide unique opportunities for research into this Viking-age treasure. Softer organic material like textiles, leather and wood very rarely survive in comparison to hard inorganic materials like stone or precious metals. Gold and silver are obviously recognised as treasure, but the surviving organic materials in the Galloway Hoard are archaeological treasures, valuable for the different scientific and forensic techniques that can be applied to them, such as radiocarbon dating.

Comparison with other collections and consultation with specialists around the world has enabled deeper understanding of the Hoard. An Anglo-Saxon runic inscription on an arm-ring fragment has revealed the name ‘Egbert’, perhaps a person associated with the Hoard’s burial. The Old English name, rather than a Scandinavian one, again causes us to question simple stereotypes about the identities of those involved with the Hoard’s accumulation and burial. More detailed scientific analysis is enabling greater precision about the date and composition of the material, which in turn offers clues to where the individual objects may have come from.

The Galloway Hoard was discovered in 2014. It was acquired by National Museums Scotland in 2017 with the support of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, ArtFund and the Scottish Government as well as major public fundraising campaign. Since then, it has been undergoing extensive conservation and research at the National Museums Collection Centre in Edinburgh.

The exhibition, which is supported by Baillie Gifford Investment Managers, will open at the National Museum of Scotland on 19 February 2021, and will tour thereafter to Kirkcudbright Galleries (summer 2021 to spring 2022) and Aberdeen Art Gallery thanks to funding from the Scottish Government.

Following the tour, research into the contents of the Galloway Hoard will continue. Part of it will go on long-term display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh with a significant and representative portion of it also displayed long-term at Kirkcudbright Galleries.

November 2020

Ends

Further information and images from:

Bruce Blacklaw, National Museums Scotland Press Office on 0131 247 4165 or b.blacklaw@nms.ac.uk

Notes to editors

- About National Museums Scotland

National Museums Scotland is one of the leading museum groups in the UK and Europe and it looks after collections of national and international importance. The organisation provides loans, partnerships, research and training in Scotland and internationally. Our individual museums are the National Museum of Scotland, the National Museum of Flight, the National Museum of Rural Life and the National War Museum. The National Museums Collection Centre in Edinburgh houses conservation and research facilities as well as collections not currently on display.

Twitter: @NtlMuseumsScot

Facebook: www.facebook.com/NationalMuseumsScotland

Instagram: @NationalMuseumsScotland - Bheireadh Oifis nam Meadhanan eadar-theangachadh Gàidhlig den bhrath-naidheachd seachad do bhuidhinn mheadhanan bharantaichte. Cuiribh fios do dh'Oifis nam Meadhanan airson bruidhinn air cinn-latha freagarrach.