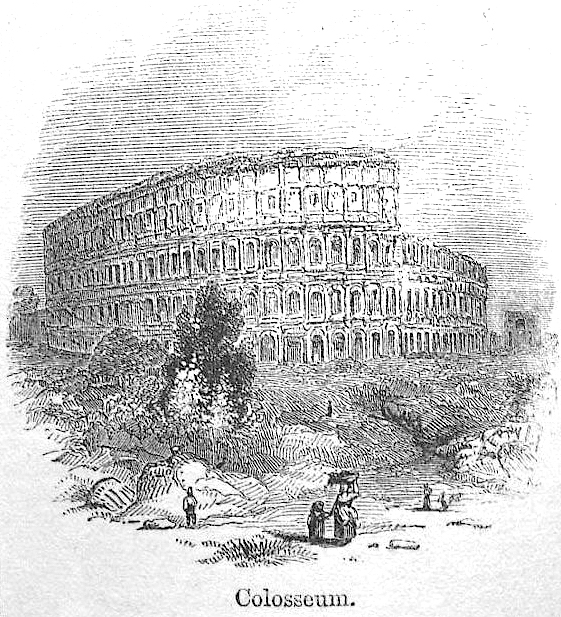

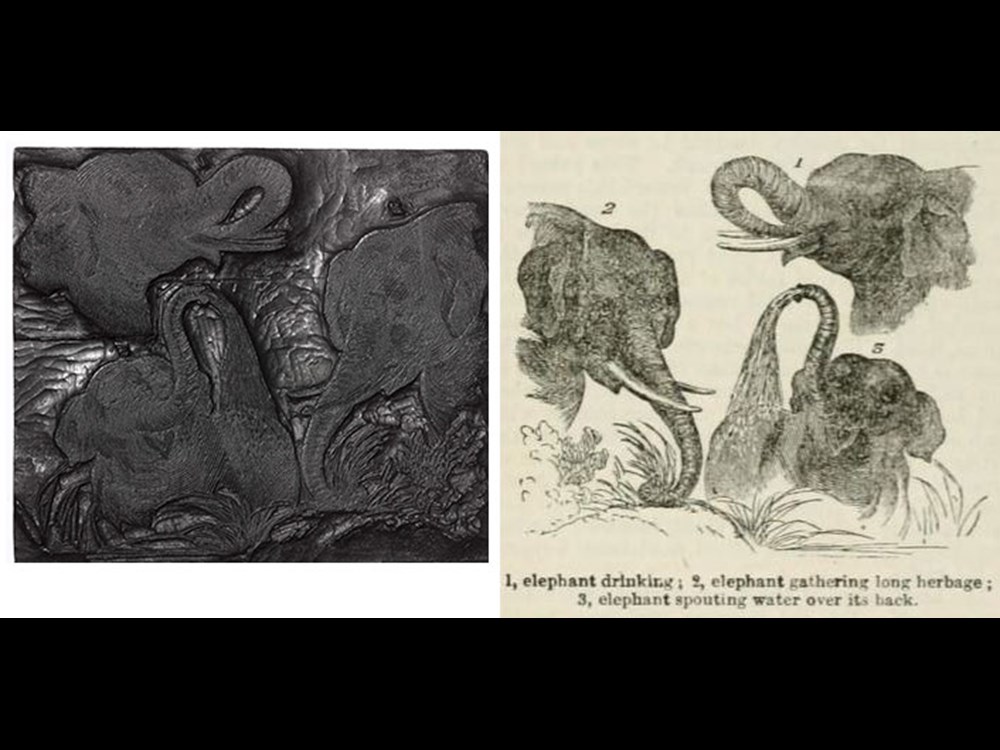

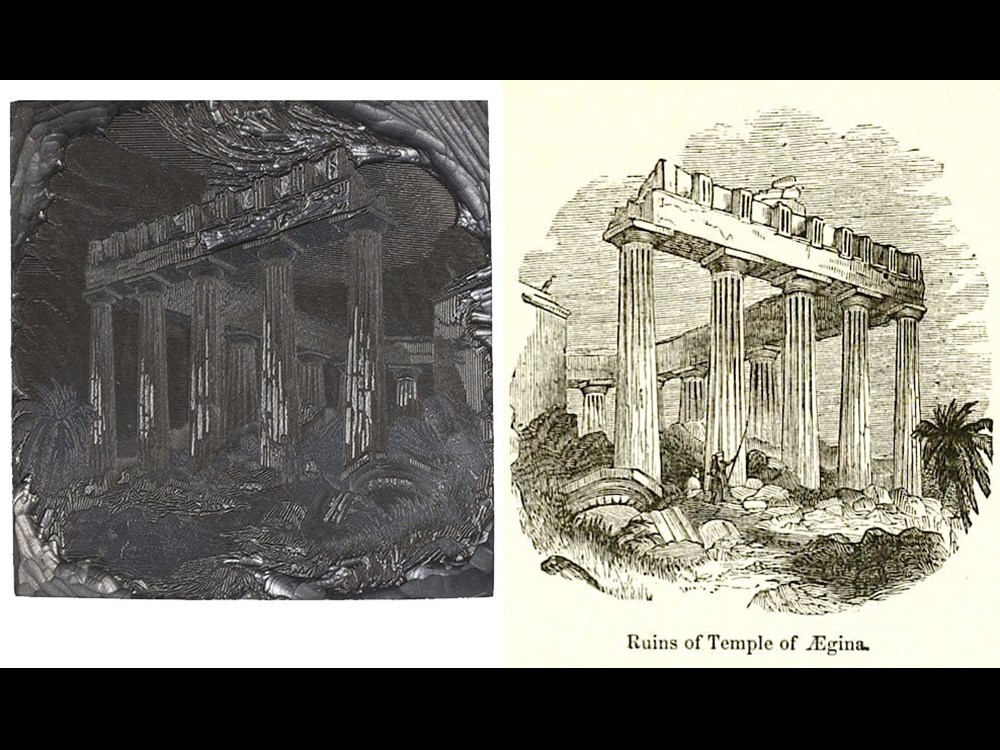

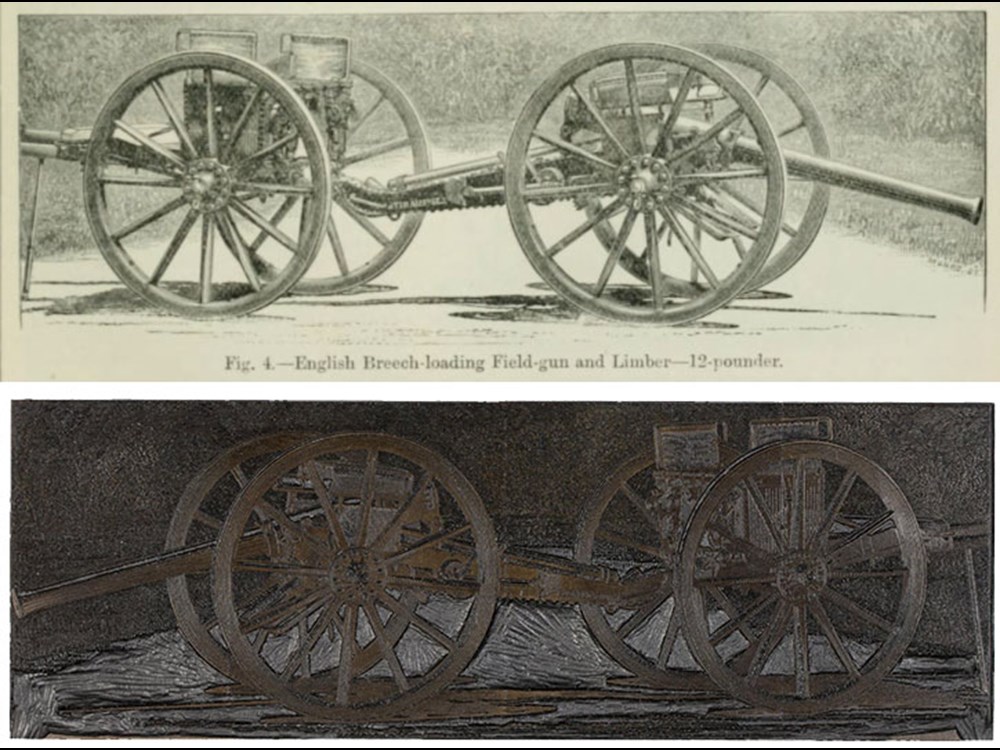

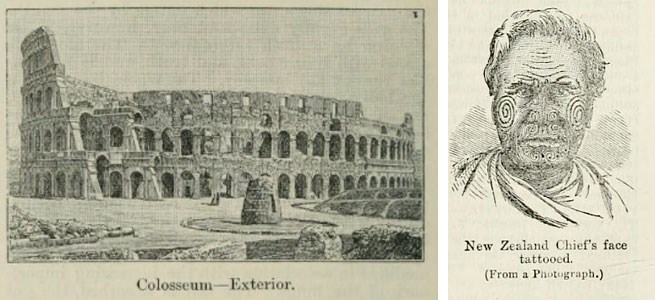

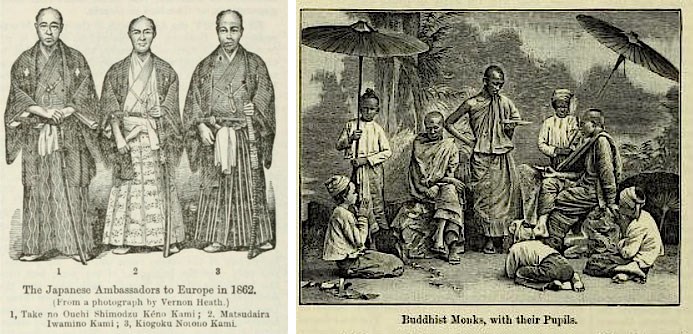

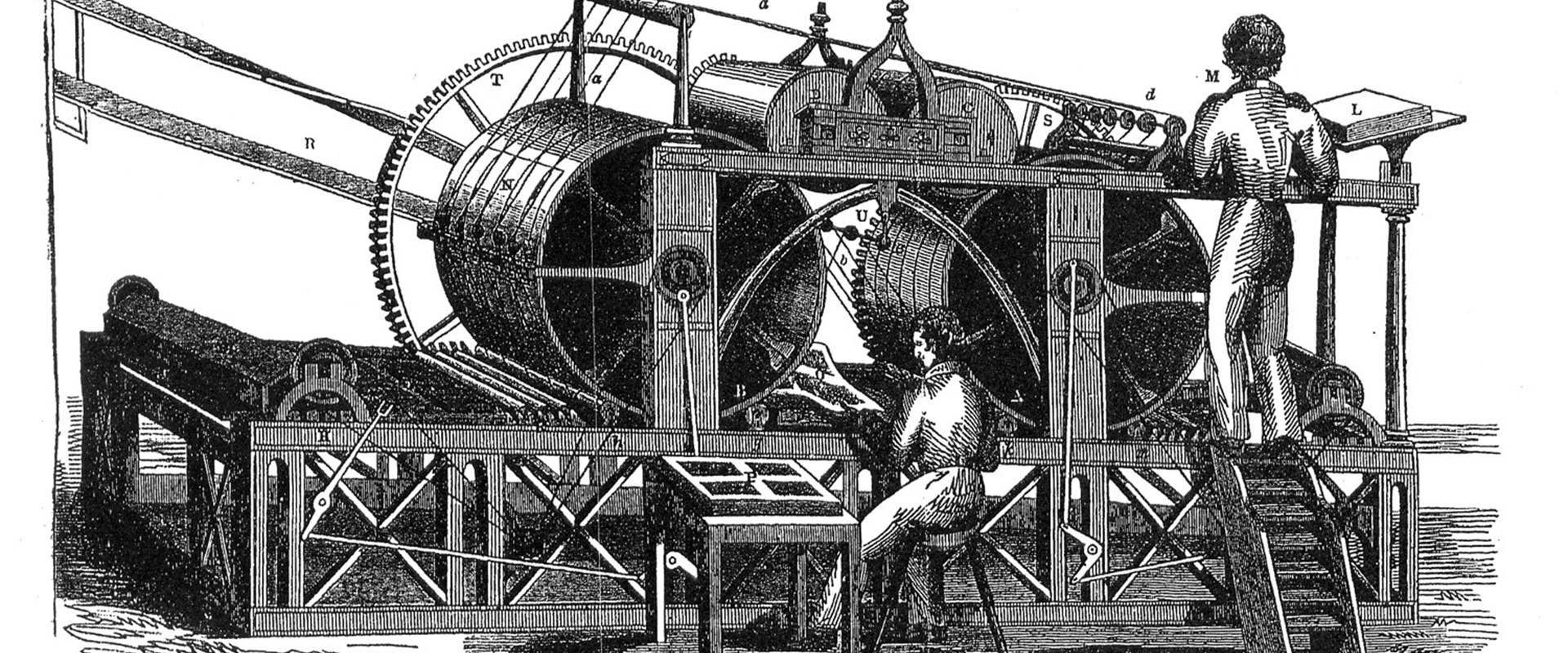

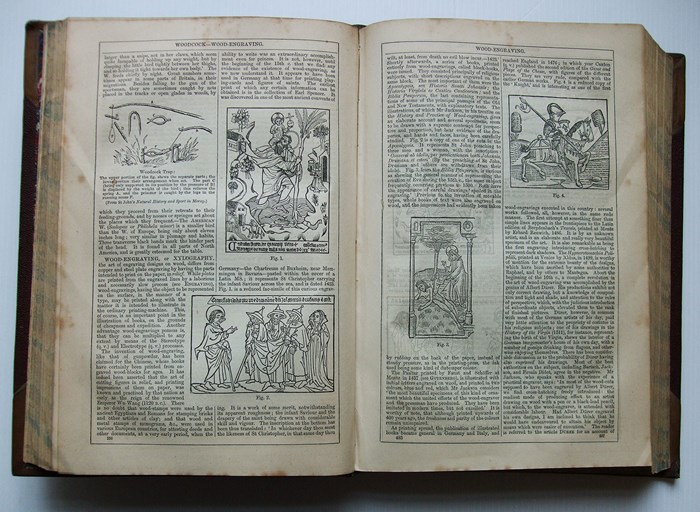

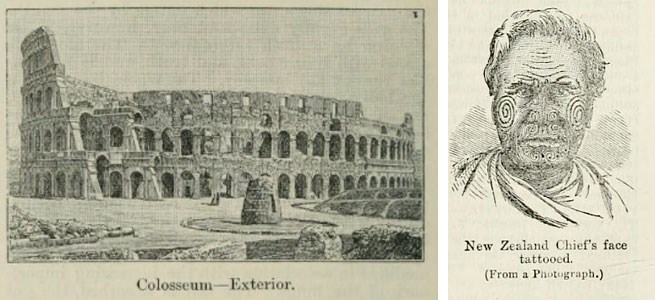

In contrast, the idea of facsimile-style representation was to depict a subject in as realistic a way as possible, or to show how it would be encountered in the real world

Photography, popular since its invention in the 1830s, provided the best facsimile of the real world. In the 1860s, however, the technology for reproducing photographs in print was cumbersome and expensive. Yet facsimile images copied from photographs, such as this Maori Chief, were thought to convey equal authority.

Above: Colosseum-Exterior, from second edition, volume 1, page 238, 1888 (left). New Zealand Chief's face tattooed (from a photograph), from first edition, volume 9, page 313, 1867 (right).