The evolving story of an ancient Egyptian coffin

News Story

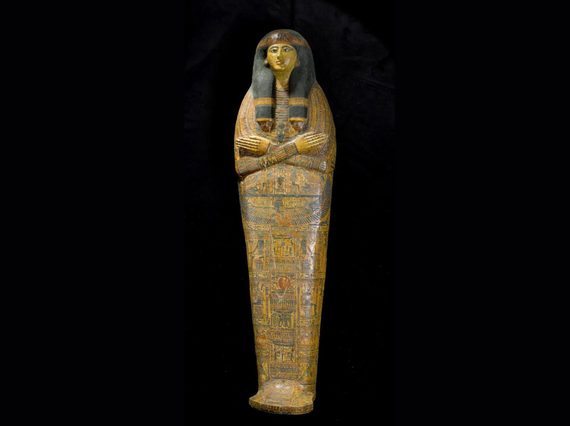

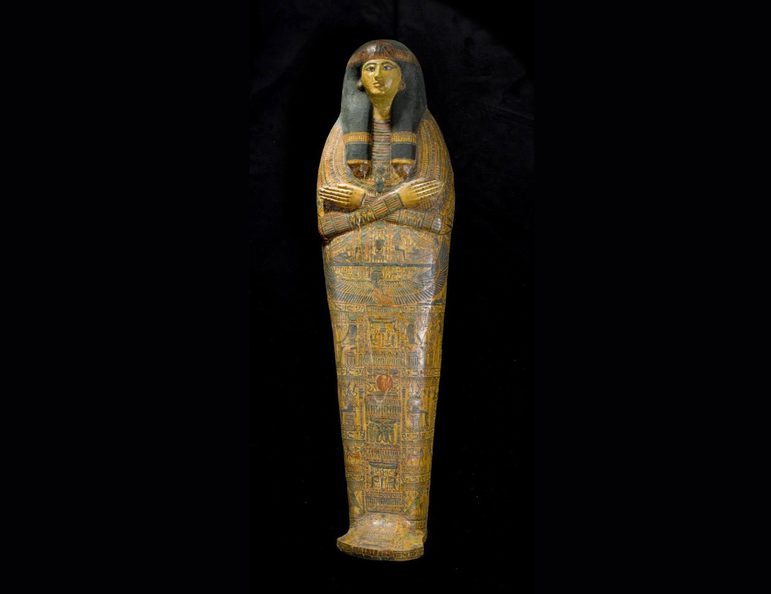

A coffin in the National Museums Scotland collection tells the stories of several different owners through the changes they made to it, helping us to reconsider ancient burial equipment as a reusable commodity. The story of how this coffin group came to be in Edinburgh also prompts us to consider histories of colonial collecting.

How did the coffin and mummified person come to be in Edinburgh?

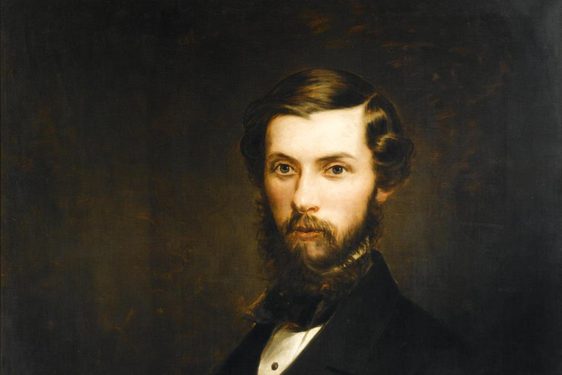

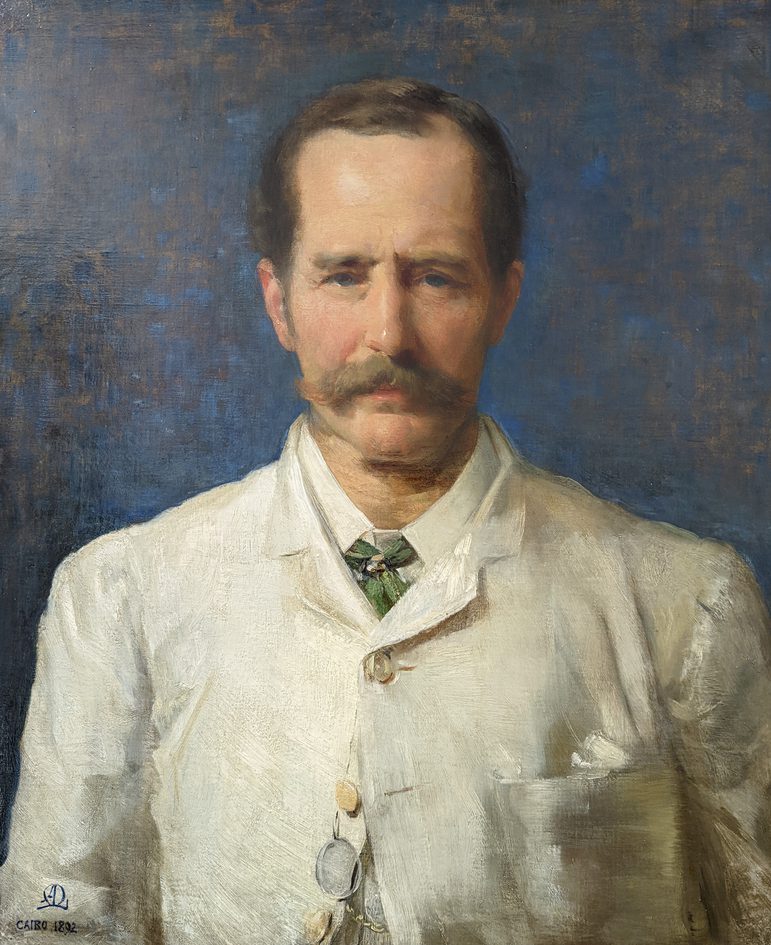

The coffin and mummified person were brought to Scotland by Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Colin Scott-Moncrieff (1836—1916). Scott-Moncrieff was a Dalkeith-born engineer employed by the East India Company and later the British Army. He made a name for himself working on irrigation systems in India and Burma (Myanmar), improving them for the benefit of the British colonial governments, who profited from their efficiency.

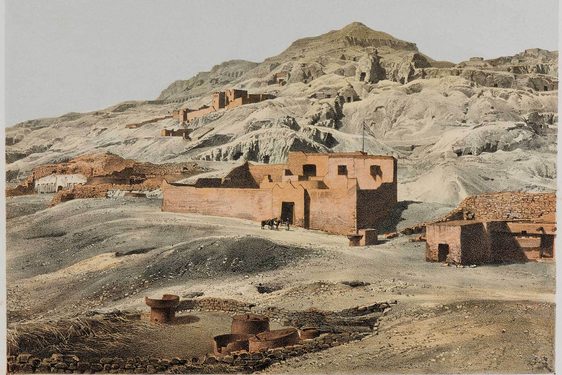

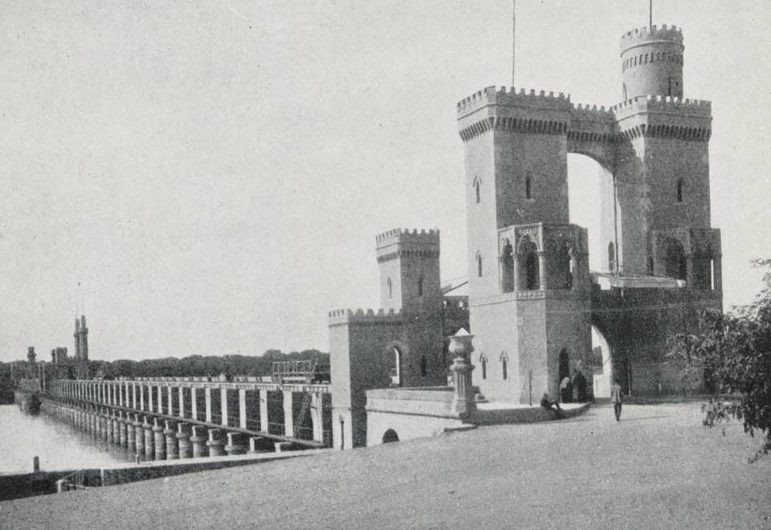

A year after the British military occupation of Egypt in 1882, Scott-Moncrieff was made Under-Secretary of State in the Public Works Department. He was entrusted with repairs to the Nile Barrage, a dam which controlled the water at the entrance to the Nile Delta, improving irrigation and increasing crop yields in the region. Egypt was strategically important to Britain as a route to India but also as a source of cotton which is a water intensive crop.

Scott-Moncrieff was an active part of European society in Cairo and was well acquainted with Gaston Maspero (1846—1916), the Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service. Maspero gave tours of the Bulaq Museum in Cairo to visiting family members of Scott-Moncrieff and he gifted objects to them. However, he also had a public disagreement with Scott-Moncrieff when the British government withheld funds that would have supported the clearance of Luxor temple.

It is unclear if Scott-Moncrieff bought this coffin set on the antiquities market or if he was given it by someone. When he returned to Scotland in 1892, he presented the coffin and mummified person to his former school, Edinburgh Academy. In 1907, the school donated them to the Royal Scottish Museum with Scott-Moncrieff’s permission.

Who owned the coffin?

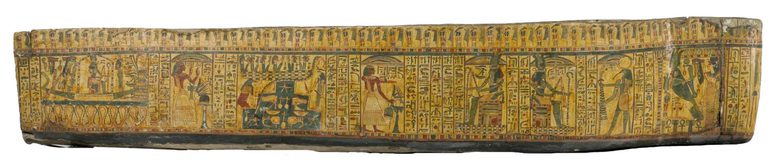

Previous research suggested that the priest Iufenamun named in the inscriptions of this coffin was Iufenamun, son of Nespaqashuty, a priest who was involved in high-profile royal reburials after a period of tomb robbery c.1100 BC. However, recent research by Kara Cooney has challenged this interpretation. Part of her reasoning behind this was based on the decorative style of the coffin, which is not of the style that was popular at the time of Iufenamun, son of Nespaqashuty.

The two men named Iufenamun also do not share the same job titles, with the coffin owner holding a title in the city of Akhmim rather than in the temples of Karnak, where the man involved in the reburials worked. This makes it less likely that the owner of the coffin was the same person.

From close examination of the coffin base and the lid, Cooney suggests that they were both reused for several burials, before being combined. She identified the remodelling of the hands and ears, recutting of the interior, alterations to the decoration and inscriptions, and several areas showing tool marks. By comparing the changes made to the lid and the base with other coffins and known style changes over time, she suggests that Tjenetweretkat, who had the nickname Tamut, was the final owner of the coffin, rather than Iufenamun.

Furthermore, it is possible that the mummified man in the coffin was not related to Iufenamun or Tjenetweretkat, and may have been placed in the coffin by a collector or dealer in Scott-Moncrieff's time to enhance its value. This means it is not possible to know if this particular arrangement is ancient or Victorian.

Reusing coffins

We might think of tombs and burials as permanent, but coffin and tomb reuse were not uncommon in ancient Egypt. The effort and raw materials that went into making tombs, coffins, and other burial objects was high, which meant that during times when resources were scarce, reuse became more common. Families also often made use of shared burials.

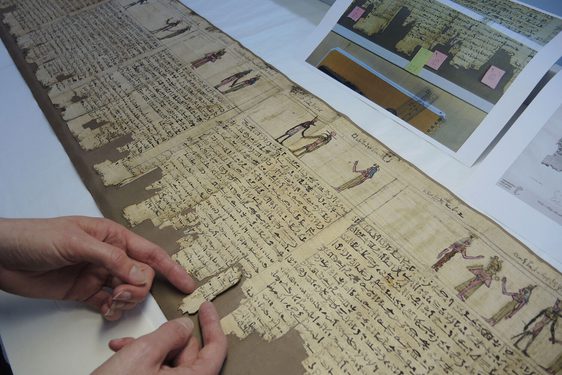

There are many stories and documents from ancient Egypt which discuss the re-use or rebuilding of tombs for new owners. For example, an ancient inscription on a limestone block at National Museums Scotland reminds the reader that ‘everyone is happiest in their own home’, in other words ‘find your own tomb!’.

One famous example here at National Museums Scotland is the ‘Rhind Tomb’ group. This tomb was initially made for a Chief of Police and his wife, in the centuries after the reign of Tutankhamun. The tomb was reused by several other people over the next thousand years. We know this because small pieces of coffins and other wooden burial goods of different ages were left behind. Eventually the tomb was sealed, enclosing the burials of a Roman-era family.