Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

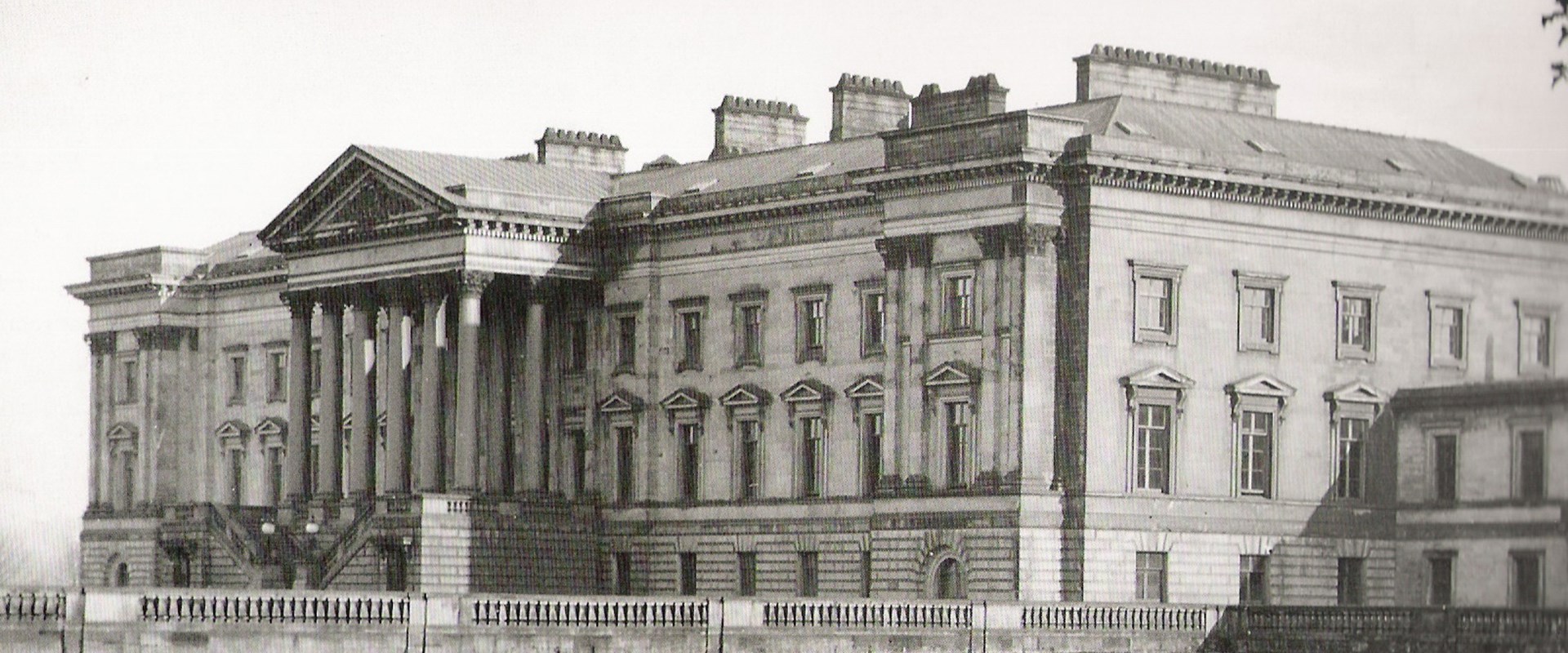

The destruction of Hamilton Palace, the grandest stately home in Britain, was one of the greatest losses to national heritage ever to happen in this country. This is the story of how Scotland’s biggest treasure trove was won and lost.

In 1882, Hamilton Palace stood grandly to the south-east of Glasgow. Home to the Dukes of Hamilton for nearly 300 years, inside its magnificent walls lived treasures to rival the Royal Collection. Exquisite furniture, famed paintings, coveted objets d’art, the finest finds from antiquity: it was the hoard of a family Daniel Defoe once called ‘great possessors.’

Yet by 1921, all of the Palace’s contents had been sold to the highest bidder and the stately home condemned for demolition. The spiral of decline started by the 10th duke’s grand architectural changes ended in subsidence caused by excessive coalmining. The cost of repairs far outstripped the family’s wealth, much of it squandered during the 19th century.

Only two enormous house sales in 1882 and 1919 saved the Hamilton fortune. For Hamilton Palace itself, there was nothing to be done: it was razed to the ground.

“It is a thousand pities that so great and historic a house should disappear. Within and without the Palace offers us of the best that the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries produced.- H. Avray Tipping, writing in Country Life during 1919

Created in 1643 for James Hamilton, the Dukedom of Hamilton is the premier Peerdom in Scotland. It is the third oldest in the United Kingdom, surpassed only by the Dukes of Norfolk and Somerset.

And the House of Hamilton has a family history to match such illustrious heritage.

Tracing their lineage from 1375 – when ‘David de Hamylton, son and heir of David fitz Walter’ first signed a writ – for 800 years the Hamiltons' power and importance shaped Scottish history and society. These men and women were kingmakers and kingbreakers, tied to British royalty by marriage and blood. They were involved in political intrigue and the struggle for Scottish independence, plagued by insanity and disastrous financial dealings, accused of treason and illegitimacy, derided as usurpers, adulterers and egotists, and even executed and exiled from their own country.

But that’s only one side of the story. The family were also scholars and romantics, generous patrons of the arts, loyal soldiers and advisers, just sheriffs and judges, ardent supporters of the local community, charitable fundraisers, successful sportspeople and aviation pioneers.

The first Duke of Hamilton was created in 1643. James Hamilton, then Earl of Arran, was ennobled for services to Charles I. An influential military leader during the Thirty Years’ War, he returned as Charles’ principal Scottish adviser when the conflict ended.

But life was not always kind to the first Duke of Hamilton. He commanded forces in Scotland during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, facing opposition from his own mother. Anne, Marchioness of Hamilton, was a colonel in the opposing Army of the Covenanters; she threatened to shoot James dead in 1639. Five years later, Charles I imprisoned the Duke in Pendennis Castle, riled by his growing misconduct and inaction during negotiations with the Covenanters.

Finally freed in 1646, James met his end only three short years later. Leading a campaign to rescue Charles I from Oliver Cromwell’s forces in 1648, he was defeated and captured at the Battle of Preston. His forces had outnumbered Cromwell’s 24,000 to 9,000.

James was decapitated on 9 March 1649, tried and condemned as a traitor.

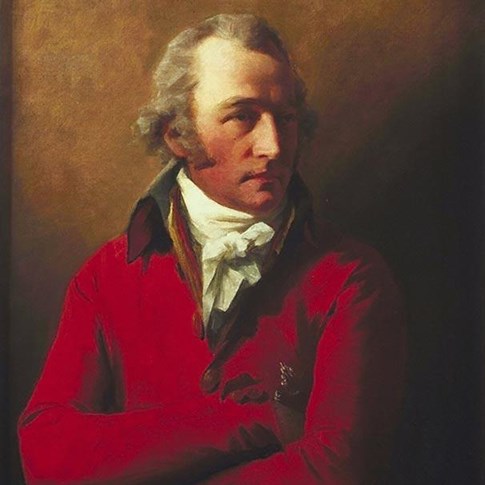

James, 1st Duke of Hamilton. Born 1606, died 1649.

James was succeeded by his brother William, Earl of Lanark. William had a quieter start in life, studying at the University of Glasgow and spending time in the court of Louis XIII of France, but quickly found himself ensnared in political machinations. Active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, his allegiance waxed and waned with Royalist gains.

He served as Member of Parliament for Portsmouth in the English House of Commons during the 1640 Short Parliament, becoming Secretary of State for Scotland in 1641. But two years later, he was arrested with James on the orders of Charles I. William escaped and reconciled with the Covenanters, fighting in the Battle of Kilsyth. By 1647, he was again treating with Charles I, signing the Engagement treaty to ally with the king in exchange for support establishing Presbyterianism in England.

Not even a year later, William fled to Holland in exile. He returned to Scotland with Charles II in 1650, dying at the Battle of Worcester.

William, 2nd Duke of Hamilton. Born 1616, died 1651.

William’s death is the one and only time the Dukedom of Hamilton passed to a woman in all its history. Anne was James’ daughter and inherited instead of her cousins; William’s will denied the succession to his daughters.

Anne should have been one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in Scotland but the death of her father and uncle left the estate with huge debts. Large parcels of Hamilton land were confiscated at this time.

She married William Douglas, 1st Earl of Selkirk in 1656. Together, they worked to settle the Hamilton debts and the evolution of Hamilton Palace as the most opulent non-royal residence in Britain began under their watchful eye. The writer Daniel Defoe described it as ‘more fit for the Court of a Prince, than the House of a Subject.’

Anne, 3rd Duchess of Hamilton. Born 1631, died 1716.

Unlike her father and uncle, Anne surrendered her title. James, her eldest son, became the 4th Duke of Hamilton in 1698. Little did she know that she would outlive him.

Like his predecessors, James’ life was characterised by political intrigue and unhappy circumstance. As a young man, he was a suspected Jacobite; when William of Orange took the English throne in 1689, James supported the unsuccessful James II and VII. A decade later, he took a seat in the Scottish Parliament in 1700 to protest a potential Union, only to change allegiance in 1705. When he wasn’t selected as a commissioner to treat for Union, James once again switched and protested the Acts.

The fourth duke was also a major investor in the Darien scheme, an imperial catastrophe which cost Scotland almost half its currency in circulation at the time.

Although a political chameleon, James actually met his end in the pursuit of money. A disputed inheritance caused trouble with Charles, 4th Duke of Mohun. On 15 November 1712 they duelled in Hyde Park and when James killed Charles, his second ran him through with a sword. The duel so shocked polite society that the law was subsequently changed so duellers could only fight with pistols.

James, 4th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1658, died 1712.

The next two successors to the Dukedom of Hamilton lived (relatively) quiet lives, although both died young. James, 5th Duke, succeeded his father in 1712; he was one of the London Foundling Hospital’s first governors. Unfortunately, he was also secretly made a Knight of the Garter and a Knight of the Thistle by the Jacobite ‘Old Pretender’ in 1723. Although viewed with suspicion by the British government, James significantly improved the Hamilton properties and estates with the help of the leading Scottish architect William Adam. Their main achievement was the hunting lodge at Chatelherault, which has now been carefully restored and is open to the public. He died aged 40, from jaundice and palsy.

His son, also James, was by contrast known for his womanising. He met society beauty Elizabeth Gunning on Valentine’s Day 1752 and demanded to marry her that same night! When the local parson refused, James and Elizabeth were secretly married at Mayfair House. Elizabeth’s wedding band was a curtain ring stripped from a bed.

The 6th duke died after catching a cold when out hunting only six years later.

James-George, their eldest son, succeeded as heir apparent when he was two years old. It was a short-lived reign; he died in 1769, aged 14. Official reports note he died of a fever or tuberculosis but society publication Dodley’s Annual Register claimed, ‘his growing so exceedingly fast is said to have been the cause of death.’ Keen gossips speculated this was because of a medical condition.

Douglas was James-George’s younger brother. His mother, nervous after losing both her husband and elder son, was keen to ensure the next heir survived. Douglas was shipped to Europe for his constitution, undertaking a Grand Tour in 1772. He travelled with Dr John Moore and his son, later to become Moore of Corunna.

Returning four years later, Douglas was a handsome, incurable romantic and risked the wrath of his family by marrying Elizabeth Anne Burrell, the fourth daughter of a barrister. Theirs was a love match which sadly descended into misery. Douglas was a paramour, with many mistresses and two illegitimate children. Elizabeth, on the other hand, never bore an heir. They divorced by Act of Parliament in 1794.

It’s been suggested that the Scottish reel ‘Hamilton House’ was named for the 8th duke and his duchess. The changes of partner reflected their real-life infidelities.

When Douglas died in 1799, the dukedom passed to his uncle, Archibald. Ever the rogue though, Douglas left the contents of Hamilton Palace itself to his illegitimate daughter with actress Harriet Pye Bennett. Archibald was forced to buy them back, or risk having nowhere to sit!

Unfortunately, Archibald suffered badly from gout and depression and soon gave up responsibility for the Hamiltons’ Scottish estates. He appointed his elder son Alexander as his ‘Commissioner’ and retired to his old home near Lancaster.

As well as serving as a Member of Parliament, Archibald was also a prominent figure in the world of Thoroughbred horse racing. Unlike his four predecessors, he attained a great age.

James, 5th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1703, died 1743.

James, 6th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1724, died 1758.

James-George, 7th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1755, died 1769.

Douglas, 8th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1756, died 1799.

Archibald, 9th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1740, died 1819.

“Never was such a magnifico as the 10th Duke- Lord Lamington, The Days of the Dandies

Of all the dukes of Hamilton, Alexander was perhaps the most ostentatious and ambitious to hold the title.

He spent his younger years in Italy, acquiring a taste for the arts which led him to collect Hamilton Palace’s finest treasures, and to carefully restore and refine its elegant rooms. Over fifty years, Alexander assembled an astonishing collection of important works of art associated with Roman and Russian Emperors, Popes and Cardinals, Queen Marie-Antoinette and the Emperor Napoleon.

Returning to Britain in 1801, he later became a Trustee of the British Museum, vice-president of the Royal Institution for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Scotland, Grand Master of the Freemasons in Scotland, and a Fellow of the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries of London. His collection of paintings, objects, books and manuscripts was eventually sold at public auction in July 1882 for the princely sum of £397,562. That’s the equivalent of almost £20 million today.

It was also in Italy that Alexander cultivated the belief that he was the true heir to the Scottish throne. His passion for arts and culture was matched only by intense pride in the Hamilton ancestry. It fuelled a lifelong belief that as a descendant of James Hamilton, regent to Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the true heir to the Scottish throne.

Alexander was also so enamoured by the Ancient Egyptians that he had mummification expert Thomas Pettigrew embalm him after his death and was buried in a sarcophagus.

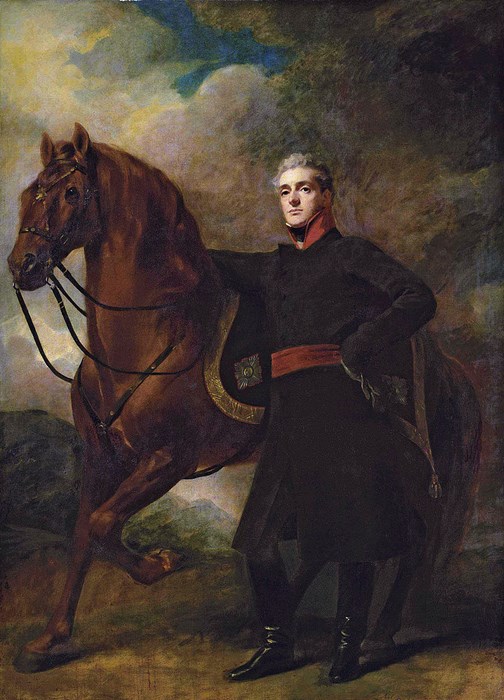

Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1767, died 1852.

William, 11th Duke of Hamilton, succeeded to the title in 1852 but spent very little time in Scotland after this and took almost no interest in his British affairs. The 10th duke was an ardent admirer of the Emperor Napoleon and persuaded his son to marry Princess Marie of Baden, the daughter of the adopted daughter of Napoleon. The couple married in 1843, spending much of their time after that at residences in Paris and Baden.

Like his father before him, William was a lavish spender. But unlike Alexander, the 11th duke lavished the family fortune not on Hamilton Palace but on a London townhouse. He bought 22 Arlington Street in St James’, London from Henry Somerset, 7th Duke of Beaufort for £60,000. That’s the equivalent of almost £3 million today. The 11th duke also developed into a major collector of old silver and other antiquities.

William, 11th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1811, died 1863.

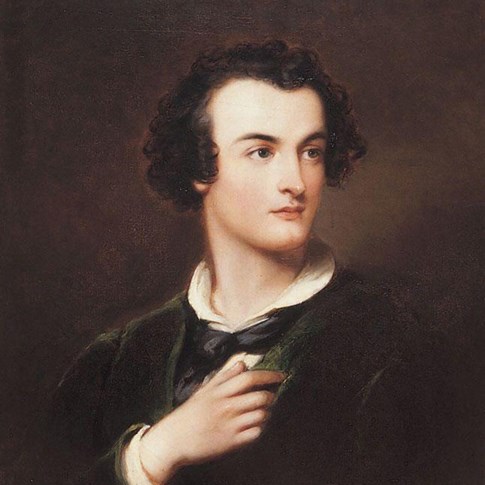

“It is the curse of his life that he has never learnt to find pleasure in aught but idlesse...- Vanity Fair, October 1873

William was the 11th duke’s eldest son and another lover of the high life; he loved horse racing and steam yachts. After his marriage in 1873, he developed Easton Park in Suffolk (which had been inherited by Alexander in 1830) into his main residence. It was closer to the major race courses and also meant that he could base his steam yacht in the south.

But as a keen boxer and sportsman, this gambling man was nearly brought to ruin – he spent the Hamilton fortune on horses. By the mid-19th century, the Hamilton estates were no longer as profitable as they once were. Although Brodick Castle in Arran and Hamilton Palace brought a regular income, the family’s debts already ran into hundreds of thousands of pounds. The 12th duke’s expenditure increased the Hamiltons’ debts to around £1.5 million. William was only saved by a lucky bet on the steeplechase race at the 1867 Grand National. The prize money restored his personal purse for the rest of his tenure as Duke of Hamilton, although it didn’t prevent the sale of many of the Palace’s finest treasures in 1882.

Hamilton Palace’s final keeper was Lieutenant Alfred Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, William’s fourth cousin. He served with the Royal Navy until 1890, when Alfred caught a rare tropical disease during a tour of duty and was partially paralysed.

He recovered and inherited the dukedom, all entailed property and assets in 1895 – and debts amounting to £1.5 million. It was a debt that would never be repaid; Hamilton Palace was its biggest casualty. Offered for use as a Royal Navy hospital during the First World War, it was slated for demolition after the conflict ended. The wear and tear of wartime medicine, coupled with subsidence caused by the Hamiltons' own overworked coal mines, meant the main family seat could no longer be maintained. The last of its contents were stripped and sold. The Palace, conceived in greatness 300 years earlier, was razed to the ground.

William, 12th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1845, died 1895.

Alfred, 13th Duke of Hamilton. Born 1862, died 1945.

For a stately home now regarded as Scotland’s greatest lost treasure trove, Hamilton Palace’s architectural beginnings belied its future. The original baroque palace was commissioned by Anne and her husband William during the 1690s, to a design by leading Scottish architect James Smith. William died in 1694, but his formidable widow pushed on and the palace was virtually complete by 1701.

Anne also employed William Morgan, a leading London woodcarver who had worked on the Chapel Royal at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, to decorate the interiors of the newly-built Palace. Five luxurious State Rooms – including a dining room, drawing room, bedroom and two dressing rooms – were clad in carved wood felled locally from Cadzow woods. This was extremely unusual for the period and a clear indication to society of the Hamiltons' wealth and power.

The Duchess' bedroom photographed for Country Living in 1919 © Country Life Picture Library

The Duchess' bedroom photographed for Country Living in 1919 © Country Life Picture Library

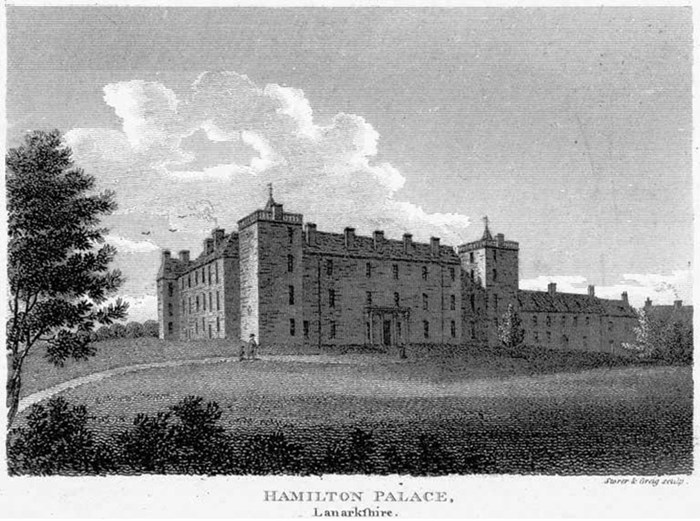

Despite its resplendent rooms, the north front of the Palace erected under Anne’s guardianship was considered unimpressive. Unsurprising then that later generations planned to replace it with something much more magnificent, a façade to reflect the Hamiltons' status as the premier peers of Scotland.

This engraving of 1807 illustrates the original north front © RCAHMS

This engraving of 1807 illustrates the original north front © RCAHMS

The first to try to improve Hamilton Palace was James, 5th duke. He employed the architect William Adam – father of the later renowned Robert Adam – from 1726 until the Duke’s death in 1743. William produced a proposal for a new north front, but James instead concentrated on building a new church in Hamilton, developing the parkland around the Palace and improving his apartments in Edinburgh.

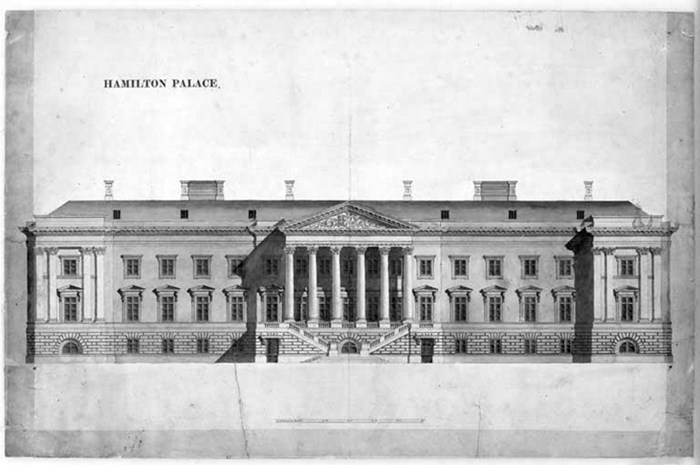

Between 1822 and 1824, the Glasgow architect David Hamilton and Alexander, 10th duke designed the now iconic north front. It was heavily influenced by Adam’s earlier proposal, but with a larger portico it was much more intimidating.

An ink and colour wash drawing of David Hamilton's original plans © Lennoxlove House Ltd

Alexander also oversaw a programme of internal renovations fit for a king. Anne’s State Rooms were furnished with imported black marble and embellished with more intricate woodwork. In the State Drawing Room, Alexander added a striking black marble chimneypiece and above this, an imposing carving of his arms as a Knight of the Garter.

Alexander was a great admirer of black marble and used it as a visually-unifying feature throughout the Palace during this period. In the 1830s for example, he installed a further four specially-made colossal black marble chimneypieces in the Long Gallery and the first-floor Grand Entrance Hall. His final flourish to the palace in the 1840s was a double staircase of hand-polished Irish black marble which cost more than £10,000 at the time – almost £500,000 today.

The Long Gallery ran the entire length of the first floor, showcasing the Palace's finest acquisitions.

The black marble staircase photographed for Country Living in 1919 © Country Life Picture Library

But a house is not a home without the trinkets of its owners, and Hamilton Palace was perhaps the biggest treasure house of them all. The fine rooms and grand entrances housed treasures to rival the Royal Collection. Many of these treasures are now in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland, their stories told across our new Art, Design and Fashion galleries.

Amongst their number is the Hamilton-Rothschild tazza. While serving as British ambassador to Russia between 1807 and 1808, the 10th duke purchased an exceptionally large Byzantine sardonyx bowl, in the belief that it was the holy water stoup of the Emperor Charlemagne. Priced at 9,000 roubles, it was his most valuable Russian purchase. In 1812 he bought an enamelled, solid gold foot, weighing almost 39 ounces, from Rundell, Bridge and Rundell for the princely sum of £241 18s 6d. It had formed part of a large gold monstrance that had been sold at auction in London the previous year as loot from the Spanish royal monastery of the Escorial, near Madrid. Recent research has revealed that the monstrance was, indeed, given to the monastery by the Emperor Philip II of Spain in the mid-16th century.

Another of Alexander’s treasures was this spectacular tea service. It was created for the Emperor Napoleon and his second wife, the Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, shortly after their wedding in 1810. Many of the main pieces – such as the double salts, sugar bowl and this punch bowl – were designed by Napoleon’s architect Charles Percier, and assembled and supplied by his goldsmith, Martin-Guillaume Biennais. It came to Hamilton Palace in 1830, bought from Charles X of France for less than half the original price of 40,000 francs.

The duke was a great admirer of Napoleon. In addition to acquiring a number of Napoleonic heirlooms, Alexander also demonstrated his opposition to the British government of the time by commissioning a very expensive portrait of the Emperor and displaying it in London in the early 1800s. After Napoleon’s defeat, he became an ardent admirer of the Emperor’s favourite sister, Princess Pauline Borghese, and offered much help – financial and otherwise – to the family.

So close was their friendship that she gifted another treasure to the Hamilton collection. This travelling service was crafted for Pauline in 1803 by Martin-Guillaume Biennais, to commemorate her marriage to Prince Camillo Borghese. The handsome wooden case conceals more than 100 silver-gilt items intended for washing and dressing, eating and drinking, and anything else that a gentlewoman might need when travelling.

Please note this video has no sound

Today, the treasures of Hamilton Palace are on display in museums and collections all over the world. National Museums Scotland, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the National Trust, the Louvre, Lennoxlove House and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts – all have carefully collected, stored, conserved and exhibited rooms and objects from Scotland’s lost treasure trove.

While Hamilton Palace no longer stands, that doesn’t mean its architecture is lost to the ages. The Old State Dining Room, for example, is now on display in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. Here at National Museums Scotland, the imposing fireplace wall from the Drawing Room is the centrepiece of our Art of Living gallery. Sold to publishing magnate William Randoph Hearst in the 1920s, it has travelled the globe for a century: to the auction rooms of London, onwards to Hearst Castle in California, resting in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, before finally journeying home to Scotland and the museum. Joining the very best of decorative European art from the last 500 years, its installation was the culmination of two years’ hard work by our conservators and curators.

Before building the fireplace in the Art of Living gallery, our conservators conducted a 'test build' at the National Museums Collection Centre, which you can see in this timelapse film.

The timelapse video below shows the wall being installed in the Art of Living gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

National Museums Scotland isn’t the only historic institution to have rescued a piece of the past. Guests at Barncluith House, an estate south of Hamilton, might not realise that they’re actually visiting the largest collection of carved stonework rescued from the Palace. Bought by estate owner James Bishop and the people of Hamilton during the 1920s, today artefacts like this armorial adorn the Barncluith gardens. They stand as a poignant physical reminder of the quality and grandeur of the Palace's architecture.

Nor has the architecture truly disappeared from Hamilton’s landscape. With no neoclassical palace to stand in the shadows of, it’s easy to forget about the lone quirky survivor of the Hamilton estates.

The Hamilton Mausoleum was a pet project of Alexander, 10th Duke: another means to reflect the glory and eminence of the premier peers in Scotland. Started in 1842 and completed in 1858, the Mausoleum stands testament both to the power of the Hamilton legacy and to Alexander’s deep love of the classical world. Originally, renowned Glasgow architect David Hamilton was commissioned to build this domed tomb in a Roman style, but it was completed by David Bryce and sculptor Alexander Handyside Ritchie.

The finished building stands 36 metres tall, with magnificent bronze doors modelled on the Florence Baptistery and an intricate marble floor designed by Edinburgh firm Wallace & Whyte. With 10,000 slabs sourced from all over the world and underfloor heating, the floor is as much a technical masterpiece as it is one of beauty.

But the real magnificence of the mausoleum lies in its symbolism. Each surface, each carving, lays bare the 10th duke’s obsession with the ancient world and his concern with the transience of life.

To enter the Mausoleum, you must choose one of three archways crowned with statues of Life, Death and Immortality. Only Death allows admittance to the tomb.

The Hamiltons are guarded by two fierce sandstone lions, one seemingly sleeping. Representing life and death, all is not as it seems; the sleeping lion has his claws extended, waiting to pounce.

How bittersweet then that the last real monument to these architects of Scottish history isn’t the palatial home and treasures they lived, loved and fought for so hard for, but the cold quiet tomb which guarded their bones and souls.