Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Aberdeen-born Annie Pirie was one of the first women in the United Kingdom to study Egyptology. Discover how this trained artist and pioneering archaeologist has left a lasting legacy.

“Of all the different dwelling places, give me, for choice, if not too long a time, a good tomb.- Annie Pirie Quibell, A Wayfarer in Egypt

Annie Abernethie Pirie Quibell (1862 – 1927) was born in Aberdeen, the daughter of William Robinson Pirie, a minister and Principal of Aberdeen University. She originally trained as an artist and exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy.

In the 1890s, she was amongst the first women to study Egyptology at University College London with the celebrated archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie. Petrie’s position at UCL had been set up there specifically because it was the only university in the UK at the time that allowed women to take degrees. The position was founded by Amelia Edwards, the novelist, Egyptologist and co-founder of the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society).

Together with his wife Hilda, Petrie excavated important archaeological sites across Egypt and made many significant discoveries, including the Qurna burial. In 1895, he invited Pirie to join his excavations. She went on to excavate at several key sites, including one of the earliest temples in Egypt, at Hierakonpolis.

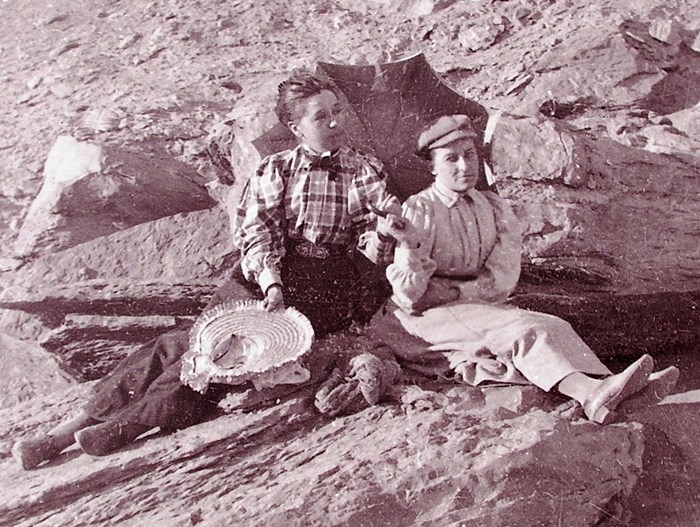

Above: Annie Pirie (right, in plaid) with her future husband's sister Kate Quibell (left) at Hierakonpolis in 1898. © Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL.

Hundreds of years before the pyramids were built, Hierakonpolis was one of the largest settlements on the Nile. Known to the ancient Egyptians as Nekhen, it was the site of a very early temple dedicated to the falcon-god Horus (c3400 BC).

During excavations in 1895, a group of objects, beautifully carved in stone, ivory and gold, were found buried in a deposit beneath the temple floor. They had been given as gifts to the god around 3000 BC. These very early finds revealed the foundations of ancient Egyptian culture; as the style of art and many of the motifs set the standard for the next 3000 years.

Above: This is a cast of one of the most important objects excavated in Egypt. The original is made of siltstone and is decorated on both sides. The largest figure represents one of the first kings of a united Egypt, King Narmer. He is shown about to attack an enemy with a mace. The original was excavated at Hierakonpolis in 1895.

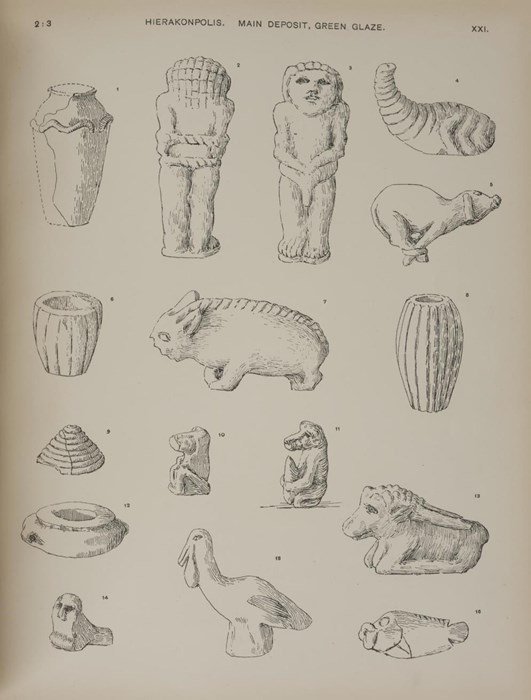

During this time, Pirie’s artistic skill was put to great use, illustrating these unique finds and sites. She produced many of the object illustrations for the excavation publications of the Egypt Exploration Society, which was founded in 1882 by the writer and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards, and which funded many of Petrie's expeditions. Pirie's illustrations include objects found at Hierakonpolis that are now in the National Museums Scotland collection.

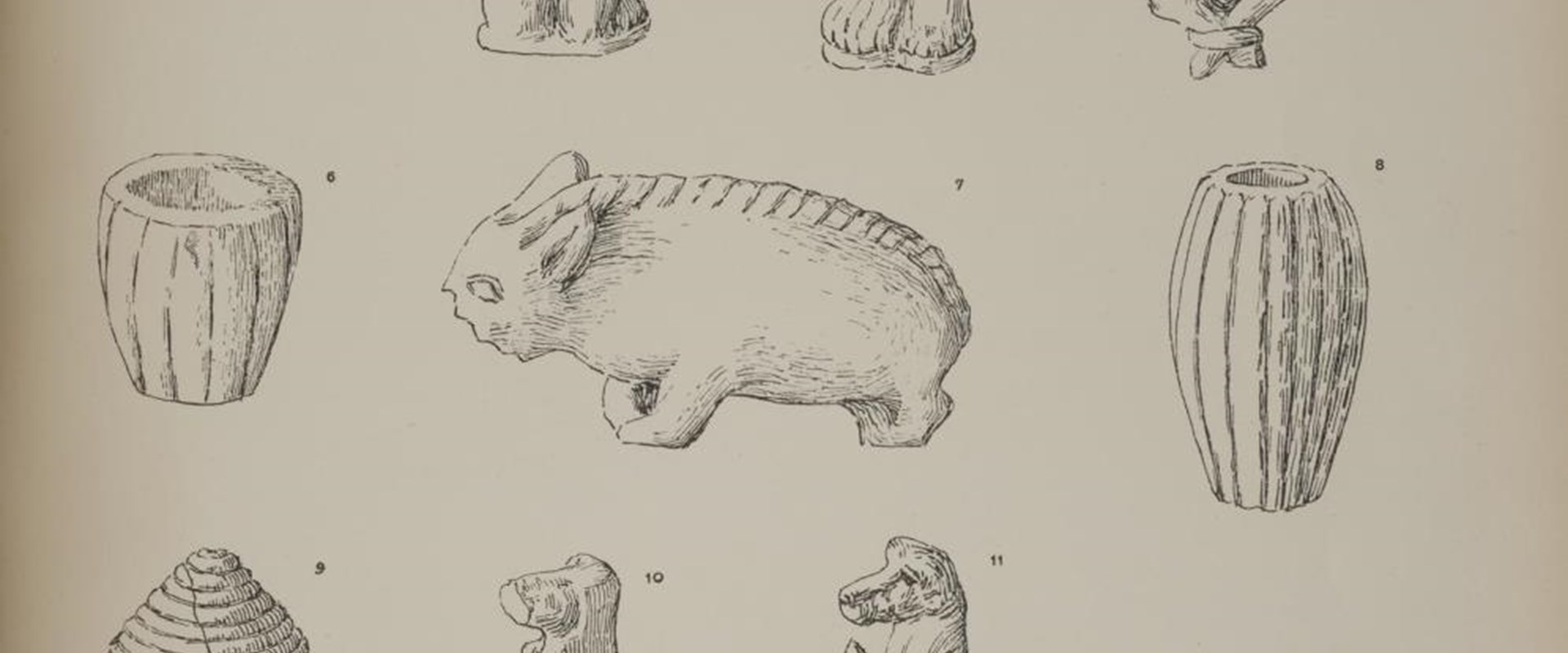

Above: You can see these faience animal figurines from the National Museums Scotland collection illustrated in Pirie's drawing (left). They were given as gifts to gain favour with the gods at the temple of Hierakonpolis, c3200–2686 BC. Clockwise from top: ape (no. 11 in Pirie's drawing), falcon (no.14), scorpion (no.4) and oryx (no.13).

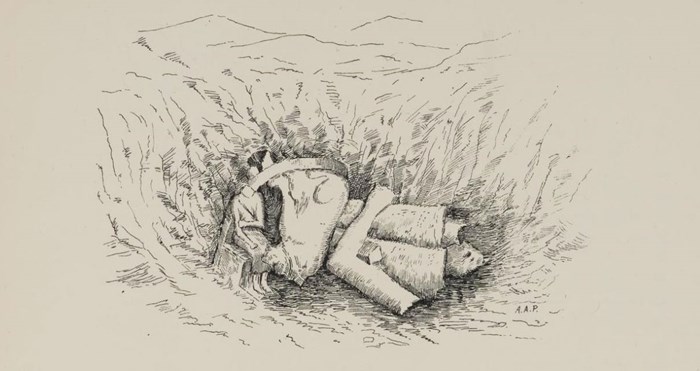

Above: Drawing of the excavation of three statues at Hierakonpolis, signed by Annie A Pirie.

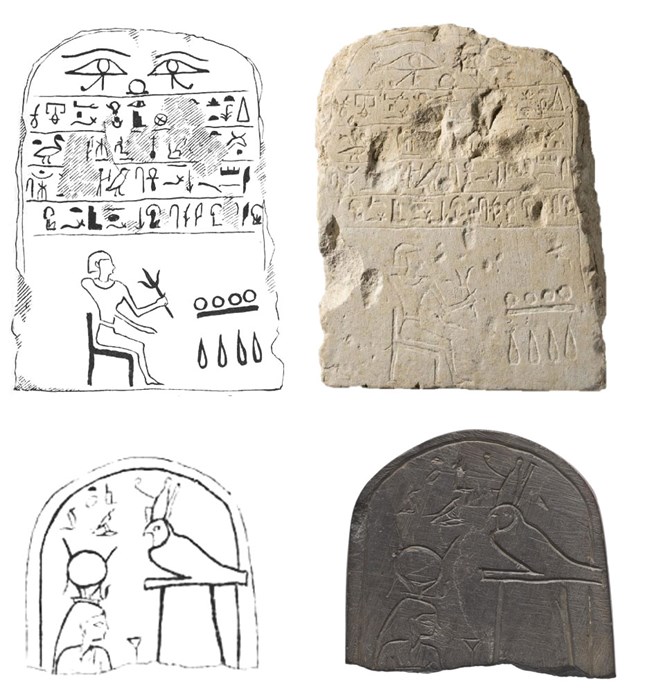

Above: Drawings made by Pirie of stelae excavated at Hierakonpolis now in the collection of National Museums Scotland.

During one of the excavations, she and Egyptologist James Quibell fell in love, while both were suffering from a bout of food poisoning (a frequent occurrence on Petrie's excavations!). They married in 1900 and worked together in Egypt until 1914, including eight years at the site of Saqqara.

Above: Annie Pirie and her husband James Quibell, January 28, 1902: HUG 1541 [Folder 10], olvwork203522. Harvard University Archives.

Alongside her illustration work, Pirie wrote Egyptological publications for the general public. Working with her husband, she produced an English translation of the Guide to the Cairo Museum in 1906. She also wrote short guides to Saqqara and the Giza Pyramids.

After returning to Britain, Pirie published two further books, Egyptian History and Art (1923), and A Wayfarer in Egypt (1925). She was also responsible for arranging the Egyptian gallery at the Marischal Museum at Aberdeen University.

She died of leukaemia 1927 at the age of 65, but left a lasting legacy, particularly through her illustrations, which are still used by researchers today.

You can see objects excavated and illustrated by Annie Pirie Quibell in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery on Level 5 at the National Museum of Scotland and in the touring exhibition Discovering Ancient Egypt.

You can also explore illustrations by the Quibells in our collections search.

Young, L. 2014. Annie Abernethie Quibell. Ancient Egypt 14 (4): 16-23.