Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

This box inscribed with the name of Pharaoh Amenhotep II is one of the finest examples of decorative woodwork to survive from ancient Egypt.

Date

c.1427-1400 BC

Made from

Cedar wood, ebony, ivory, gold, copper alloy, faience

Made for

King Amenhotep II of Egypt

Dimensions

Height 21.7 cm, diameter 12 cm

Acquired

By Alexander Henry Rhind

Museum reference

On display

Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

Amenhotep II built a temple, near the pyramids at Giza, dedicated to the Great Sphinx, which was already over 1,000 years old by then.

This box was made in honour of the Pharaoh Amenhotep II, who ruled ancient Egypt during the 18th Dynasty (around 1427–1400 BC). He succeeded to the throne after his father Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC), under whose rule Egypt’s empire probably reached its greatest extent, stretching from modern Syria to Sudan.

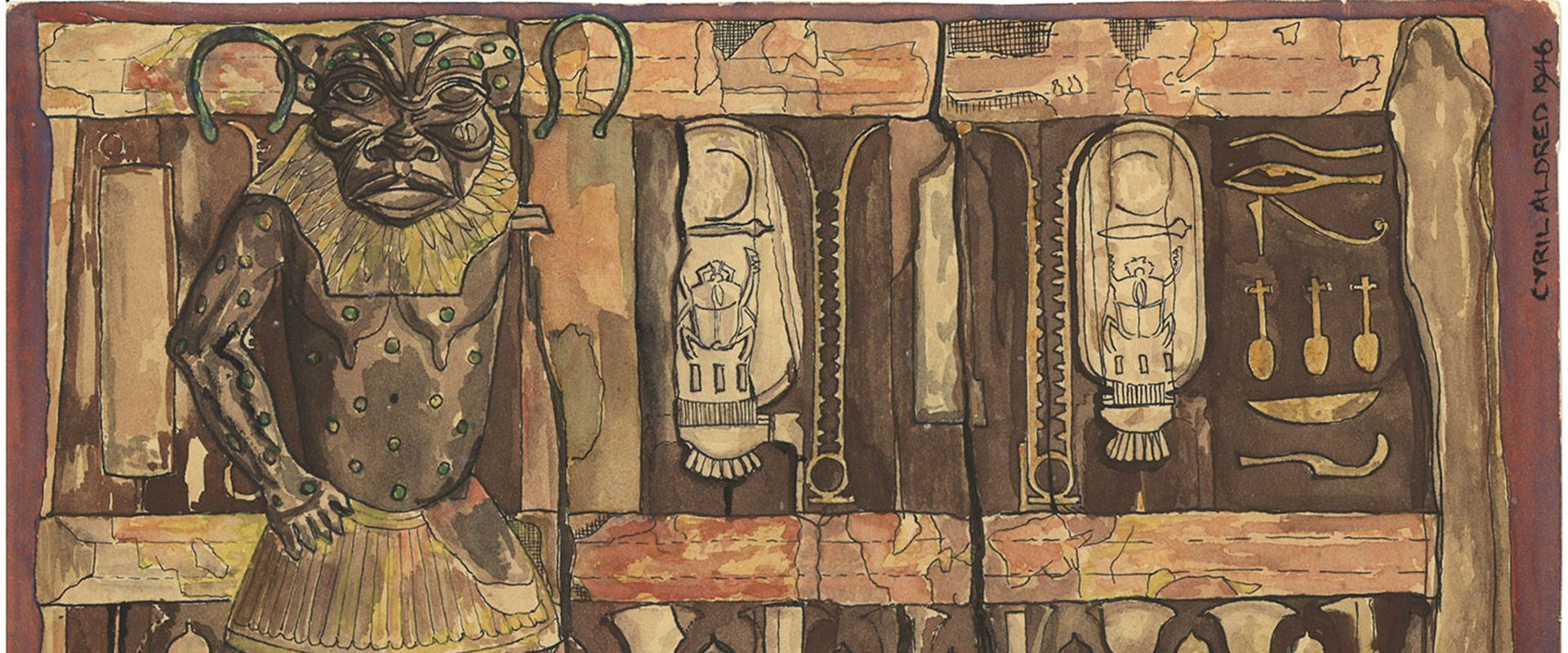

Above: Decorative Box of Pharaoh Amenhotep II

The fragmentary box is richly decorated with exotic materials from different areas of the ancient Mediterranean, signifying the extent of the king’s empire and its wealth. The main body is made of cedar wood, which was imported from Lebanon and valued for its quality, as suitable sources of wood were not abundant in Egypt.

The gold may have been mined in Egypt’s Eastern Desert or in Nubia (ancient Sudan). The box is overlaid with ivory plaques, made from either hippo or elephant tusk. Elephants were not native to Egypt and ivory was imported or given as tribute from further south in Africa. The veneers of ebony, a highly-prized dark hardwood, probably came from the land of Punt with whom the Egyptians traded. Our name for this wood, ‘ebony’ actually comes from the ancient Egyptian name for it, ‘hebeny’.

Above: A less ornate wooden box also dating to the 18th Dynasty, from Sedment.

The box is a much more elaborate version of the types of wooden containers often found in ancient Egyptian tombs. The decorative box of Amenhotep II was probably used to hold cosmetics or expensive perfumes. It likely belonged to the king himself or a member of his family, although it is also possible that he could have given it as a gift to an important high official. The closest parallels to such an elaborate wooden box as this are those found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BC), and in the tomb of his grandparents Yuya and Tjuyu.

Amenhotep II was not originally the intended heir to the throne; he only became crown prince after his elder brother died, and he came to the throne at age 18. While still a prince, he served as a military commander, and he was renowned for his athletic prowess, much like his father. It was said that he once shot four arrows through four copper targets, each one palm thick, while riding on horseback.

The stela (large inscribed stone slab) of Amenhotep II at Giza tells of his strength and endurance:

“Strong of arms, untiring when he took the oar, he rowed at the stern of his falcon-boat as the stroke-oar for two hundred men. Pausing after they had rowed half a mile, they were weak, limp in body, and breathless, while his majesty was strong under his oar of twenty cubits in length. He stopped and landed his falcon-boat only after he had done three miles of rowing without interrupting his stroke. Faces shone as they saw him do this.

Amenhotep II led numerous military campaigns over the course of his reign, but later in his reign he seems to have achieved peace with Egypt’s neighbours.

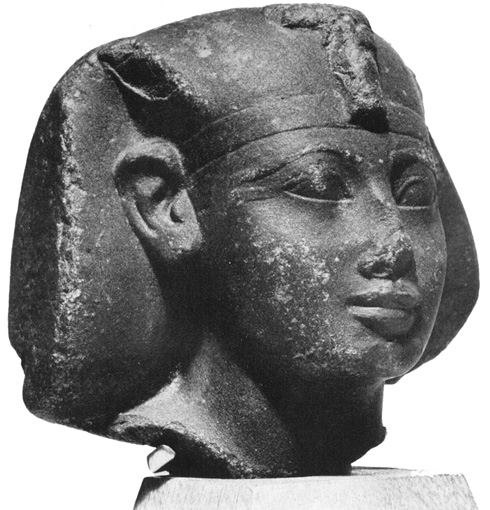

Above: Head of an 18th Dynasty king thought to be Amenhotep II.

The main figure depicted on the decorative box of Amenhotep II is a protective god and household guardian known as Bes. A number of similar such deities are known from ancient Egypt, but in the absence of an inscription identifying the figure specifically, he is usually referred to as Bes.

Bes is depicted as a dwarf with lion-like features and sometimes wears a Nubian-style headdress with feathers. In ancient Egypt, dwarfs were thought to be emblematic of good fortune and many such individuals worked as entertainers; they were also considered to be very skillful, working as expert craftsmen, or even as important state officials to the king.

As a joyful symbol of good luck, Bes is sometimes shown dancing and playing the tambourine, while his protective role is evident from his rather fearsome appearance, which was intended to scare off potential dangers and evil spirits. He is often depicted brandishing knives and sticking out his tongue. He is somewhat comparable to more modern European gargoyles whose presence on churches was intended to ward off evil. Bes’ popularity spread throughout the ancient Mediterranean and depictions of him have been found in Cyprus, Assyria, and elsewhere.

Above: Images of the god Bes from the Ancient Egypt collection.

As a household guardian and protector of the family, Bes frequently appears as a decorative and protective element on amulets, and household items such as headrests and furniture. Another wooden figure of Bes in the National Museums Scotland collection probably comes from a piece of furniture, possibly from the back of a chair.

Although he is generally thought of as a domestic god, worshipped in the home, as opposed to one of the state gods, such as the sun god Ra, who was worshipped in huge temples built by the pharaohs, Bes was obviously still considered worthy enough to feature on a household item in the palace of a king.

The box of Amenhotep II features a number of other decorative elements in addition to the main figure of the god Bes. The oval-shaped ivory plaques depict a name of Amenhotep II within a cartouche, an oval used to encircle royal names, which symbolised eternity. Ancient Egyptian names generally took the form of phrases that described their owner in positive terms, often in relation to a god or goddess.

An Egyptian king generally had five names: his birth name, plus four new names which he adopted at his coronation in order to emphasise his divine right to rule and convey a kind of mission statement for his reign. Two of the king’s names were typically written in cartouches, the birth name and the throne name.

Only Amenhotep II’s throne name, Aakheperure, appears on the box, but it is clear that there are several inlays missing which would have contained his birth name, Amenhotep. Aakheperure means ‘Great are the manifestations of the sun god Ra’, while Amenhotep means ‘the god Amun is satisfied’.

The royal names on the box are surrounded by further symbols. The cartouches sit on top of the Egyptian hieroglyph for ‘gold’, which was associated with divinity and eternity. On either side of each cartouche are notched palm ribs. The ribs of palm tree branches were used as a method of recording time; after being stripped of their leaves, the palm ribs were notched to serve as a tally for counting days. A palm rib acted as the hieroglyph for ‘year’ and as a symbol of a long reign. On the box, the palm ribs are depicted on top of circular shen rings, another ancient Egyptian symbol of eternity. Papyrus plants are depicted on the lower half of the box. The papyrus plant and the colour green symbolised life, growth, rebirth, happiness, and success.

Together all of the decoration on the box served to ensure a long and successful reign for King Amenhotep II.

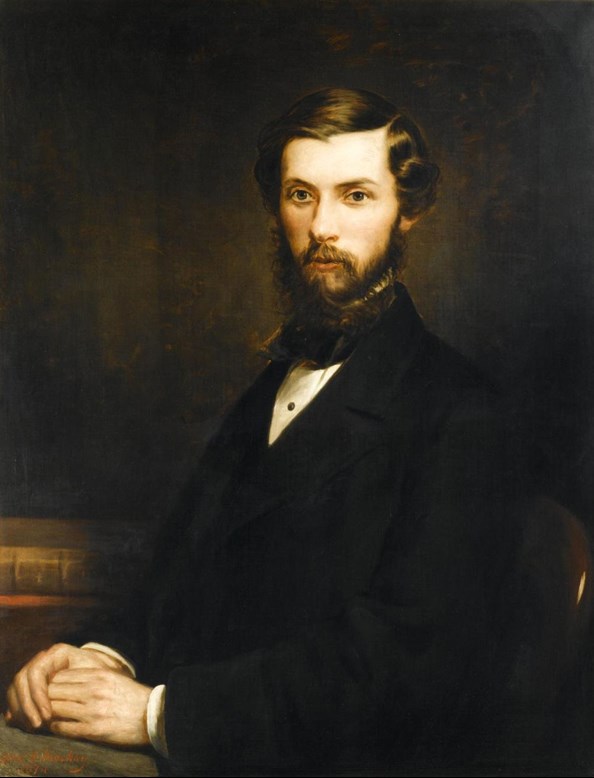

The origin of the Amenhotep II box is something of a mystery, although it is thought to have probably been brought back from Egypt by Alexander Henry Rhind (1833–1863), a young Scottish archaeologist, who was the first person to pioneer archaeological recording in Egypt in the 1850s.

National Museums Scotland holds several hundred objects brought back by Rhind, including a complete burial assemblage from an intact Roman Egyptian tomb, which he discovered in Thebes. The start to his remarkable career was cut short when he died at the age of just 29, but the legacy he left to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland continues in their annual Rhind lectures.

Portrait of Alexander Henry Rhind of Sibster, oil on canvas, by Alexander S. Mackay, 1874

Despite Rhind’s high standards of recording for the era, the exact origin of the box is not clear. It was reportedly found broken in several pieces in a box of Rhind’s miscellaneous finds by the curator of the National Museum of Antiquities, Joseph Anderson (1832–1916), in the late 19th century.

A later museum curator, Egyptologist Cyril Aldred (1914–1991), proposed that the box must have been excavated by Rhind in the same tomb in which he had made another remarkable discovery: the mummified remains of the daughters of Thutmose IV (1400–1390 BC), the son of Amenhotep II.

The tomb in which they were found, in Sheikh ‘Abd el-Qurna on the west bank of Thebes (modern Luxor), would not have been their original burial place. To protect the mummified bodies of the royals from the extensive looting going on during the 21st Dynasty (1069-945 BC), they were carefully labelled with each of the princesses’ names and titles, and then reburied in a more hidden and anonymous tomb.

The bodies found by Rhind were the granddaughters of Amenhotep II, so this remains the best conjecture as to the provenance of the box. Its exact origin remains a mystery.

Above: Several of the mummy labels of the daughters of Thutmose IV.

The box of Amenhotep II survived in a fragmentary state. Curator Cyril Aldred meticulously recorded the box in its original state in a detailed line drawing and watercolour before he commissioned its restoration, probably in the 1950s. The lid, base, and back of the cylindrical box are still missing, but other damaged elements of the figure of Bes have been restored. If you compare the drawings to the object today, you can see that Bes’ right arm and foot as well as his tongue were originally missing and have now been reconstructed.

Above: Drawing of the box by Cyril Aldred.

The box drew the fascination of another pioneering archaeologist, Sir Flinders Petrie, who wrote an article on the box in 1895. Petrie is often called the ‘Father of Egyptology’. Alexander Henry Rhind first employed systematic recording techniques almost 30 years before Petrie started working in Egypt, but his young career was cut short while Petrie was able to develop further advanced techniques over the course of his career of almost 60 years.

Petrie was intrigued by the Amenhotep II box’s beauty and decorative symbolism, and concluded his article by writing:

Petrie wrote:

“The whole piece is a very interesting example of the fine work of that most wealthy and luxurious period, the 18th Dynasty.