Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

This block is one of the few surviving casing stones from the Great Pyramid of Giza, built for King Khufu. It is the only pyramid casing stone on display outside Egypt.

Date

c.2589–2566 BC

Made from

Limestone

From

Great Pyramid of King Khufu, Giza, Egypt

Dimensions

width 685mm x depth 860mm x height 546mm x length of sloping side 612mm

Weight

298kg

Museum reference

On display

Ancient Egypt Rediscovered, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

Originally standing at 146.5m high, the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years, until the construction of Lincoln Cathedral in the 14th century.

Khufu was the King of Egypt around 2500 BC. Also known as Cheops, which was the ancient Greek rendering of his name, his biggest legacy became one of the Seven Wonders of the World: the Great Pyramid, the oldest and largest of the pyramids at Giza.

Around 5.5 million tonnes of limestone, 8,000 tonnes of granite (transported from Aswan, 800km away), and 500,000 tonnes of mortar were used to build the Great Pyramid.

This mighty stone formed part of an outer layer of fine white limestone that would have made the sides completely smooth. It was polished until it shone so that the pyramid would have gleamed in the sun. The limestone casing blocks came from quarries at Tura 15km downriver from Giza.

Above: The Great Pyramid casing stone.

By the 19th century, most of the casing stones had been removed and used for other building work, although some can still be seen at the foot of the pyramid.

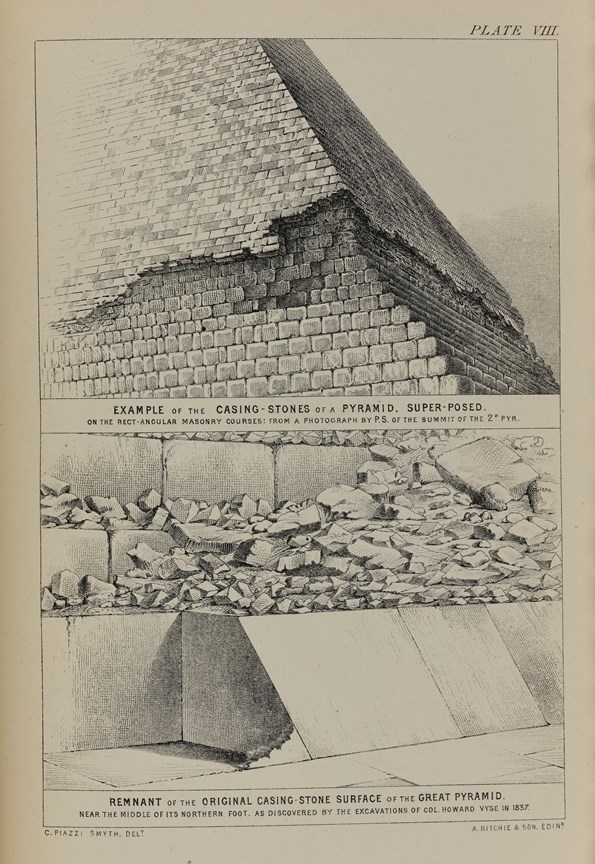

Above: Plate from Charles Piazzi Smyth’s publication Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid showing some of the casing stones still in situ at the base.

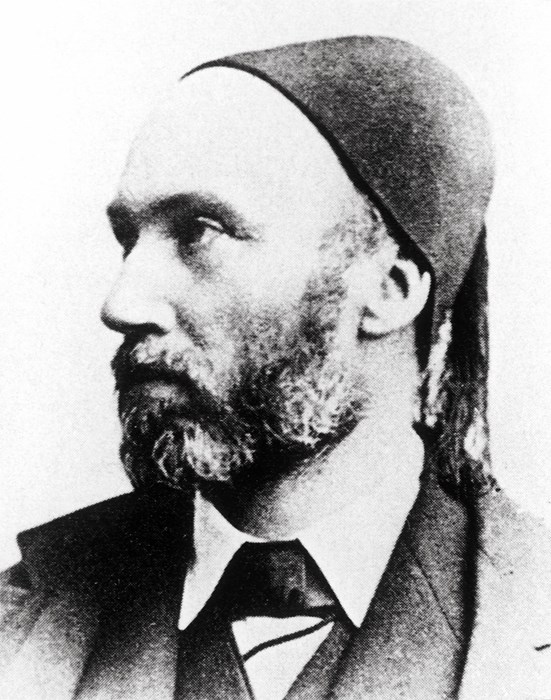

The stone came to the UK in 1872 as a result of work undertaken by Charles Piazzi Smyth, Astronomer Royal of Scotland. In 1865, Piazzi Smyth carried out the first largely accurate survey of the Great Pyramid, which he published in several books and articles. Piazzi Smyth was given official permission to carry out this work by the Viceroy of Egypt, Ismail Pasha, and he received assistance from the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the Governor of Giza. These permissions are outlined in his publications, including his 1867 book Life and Work at the Great Pyramid (vol. 1, pp. ix, 4-8, 29-30).

Piazzi Smyth had planned to do further survey work at Giza, but ill-health led him to request the assistance of his friend Dr James Grant Bey and Waynman Dixon instead. Grant was physician to the Viceroy and a well-known figure in Egyptological circles in Cairo. Waynman Dixon was a structural engineer who was building a bridge in Cairo. Dixon and Grant carried out their work at Giza in 1872 with the permission of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

During their time in Giza, they found a casing stone among the rubble at the base of the pyramid where road building work had been carried out by the Egyptian government a few years earlier. Dixon undertook the transportation of the stone back to Edinburgh for Piazzi Smyth.

“Some interesting discoveries have been made in and about the Pyramids of Ghizeh by Mr. John and Mr. Waynman Dixon of London, assisted by the English physician in Cairo, Dr. Grant… Exploring among these rubbish heaps, Mr. Waynman Dixon lately discovered this loose specimen, just in time to save its being broken up and used in building near there. This stone is just 25 in. long, the exact dimensions, according to Professor Piazzi Smyth, the Astronomer Royal of Scotland, of the ancient pyramid cubit. The stone has been sent to Professor Smyth.- The Graphic, Dec 7, 1872

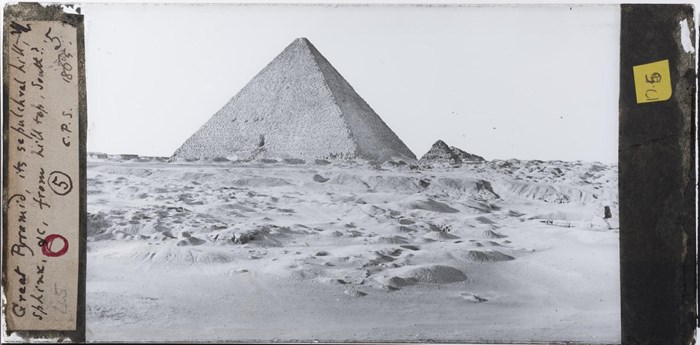

Above: Glass plate photographic negative taken in 1865 by Charles Piazzi Smyth of the 'Great Pyramid, its sepulchral hill, the Sphinx, &c, from hill top, south?' © Royal Observatory Edinburgh CPS Archives.

It went on display in a custom-made glass case in the library of the Royal Observatory of Scotland and residence of the Astronomer Royal. It was donated to the National Collection by the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, in 1955.

In 1865, the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819–1900) and his wife Jessie, a geologist, completed the most accurate survey of the Great Pyramid of Giza to date. They took thousands of detailed measurements and the first photographs of the pyramid’s internal chambers.

Before becoming interested in measuring the Great Pyramid, Piazzi Smyth was already a pioneering scientist in the fields of high-altitude astronomy, spectroscopy and photography. He was also responsible for instituting the one o’clock gun in Edinburgh.

Above: Charles Piazzi Smyth. © Science Photo Library.

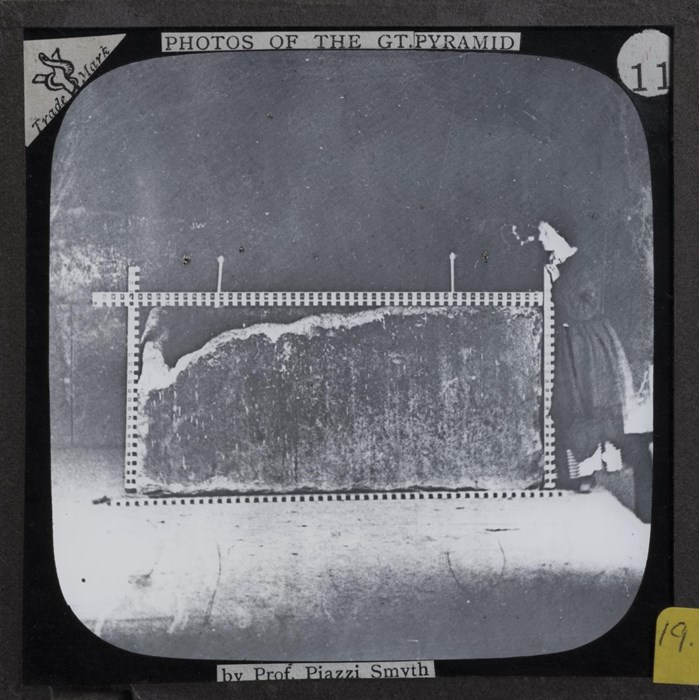

Above: Glass lantern slide taken by Charles Piazzi Smyth showing Jessie Piazzi Smyth standing next to the sarcophagus in the King's Chamber in the Pyramid of Khufu. © Royal Observatory Edinburgh CPS Archives

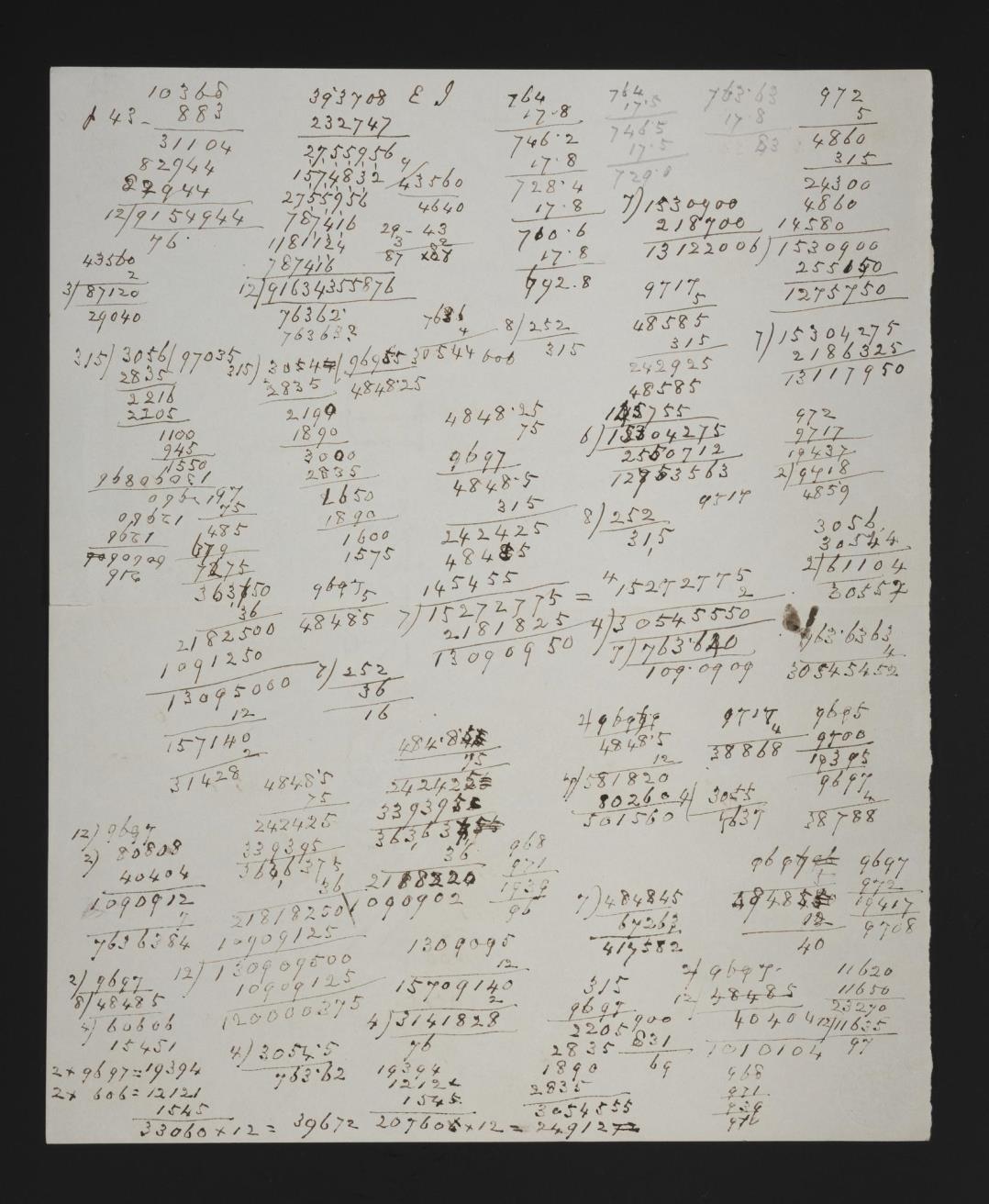

Above: Paper with handwritten mathematical calculations and notations in the handwriting of Charles Piazzi Smyth, found with a manuscript of John Taylor's 'The Mystery of the Pyramids Explained', a work which influenced him. © Royal Observatory Edinburgh CPS Archives.

Piazzi Smyth decided that he would conduct a survey of the Great Pyramid when he found other surveys too inaccurate to use to test his theories. Like many Victorians, Piazzi Smyth was influenced by evangelical Christianity, championing the existence of a ‘pyramid inch’, a unit of measurement handed down by God. This became a political argument as well, as the British inch was at odds with the newly introduced French centimetre. His theories about this unit of measurement were ultimately disproved. Nevertheless, his books and lectures inspired many to begin research in Egypt; including the person whose survey work would disprove his!

Charles Piazzi Smyth resigned as Astronomer Royal in 1888 and retired to Ripon in Yorkshire, where he died in 1900. He was buried at St John's Church in the village of Sharow, where his grave is marked by, of course, a pyramid.

Above: Charles Piazzi Smyth's pyramid-shaped gravestone. Photo by Gordon Hatton, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Nature, Nov 28 1872, pp. 71-72.

Nature, Dec 26, 1872, p. 146.

The Graphic, Dec 7, 1872, pp. 530, 545.

Lightbody, David Ian, 2016, ‘Biography of a Great Pyramid Casing Stone’, Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture 1, pp. 39-56.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1867a, ‘A Notice of Recent Measures at the Great Pyramid’, Transactions of the Royal Society Edinburgh XXIV, pp. 385-406.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1867b, Life and Work at the Great Pyramid, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas).

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1874, Our inheritance in the Great Pyramid: including all the most important discoveries up to the present time (London: Isbister), pp. 489-492.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1880, Our inheritance in the Great Pyramid: including all the most important discoveries up to the present time, 4th edition (London: Isbister), pp. 28, 29, 489-492.