Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Discover some of the treasures within the National Museum Scotland's significant collection of oracle bones, the second largest in the world outside of China. Inscribed with the earliest known Chinese writing, the bones were used for divination during the late Shang dynasty (c.1200-1050 BC).

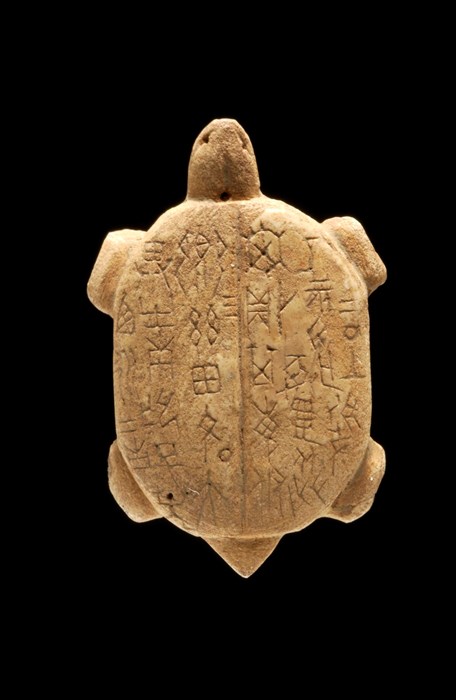

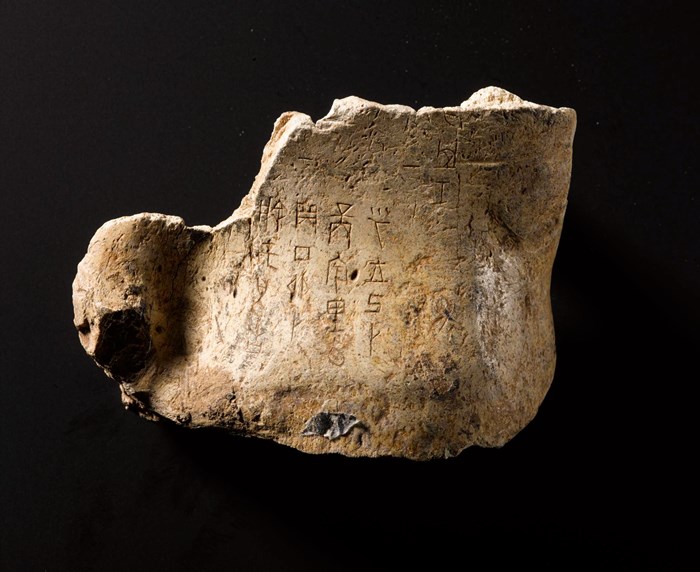

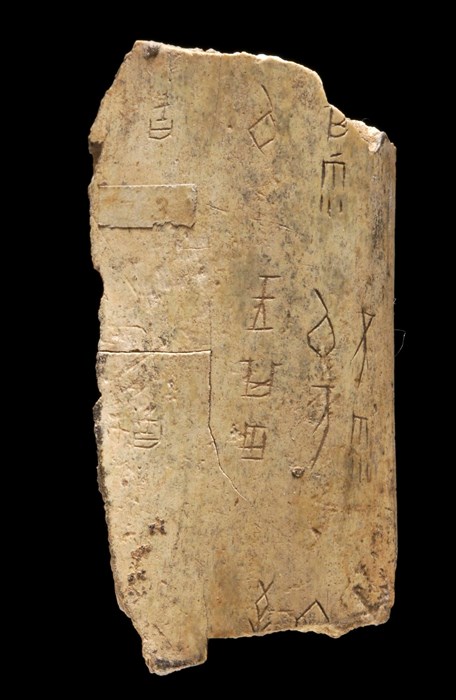

Oracle bones are parts of animal bone, used in divination ceremonies in ancient China. They are often made from either the shoulder bone of an ox, or the lower side of a tortoise’s shell (known as the plastron). National Museums Scotland’s collection of oracle bones dates from the late Shang dynasty (c.1200–1050 BC) and was found at Yinxu site near Anyang city, in central China.

The oracle bone divination ceremony was a way to seek guidance from deities or ancestors. People sought advice on topics ranging from military strategy, the harvest, childbirth and hunting, to the cause of the king’s toothache.

Many oracle bones feature inscriptions recording the details of the divination ceremonies. Often the date, the person carrying out the ceremony, the question asked, the interpretation, and sometimes even the eventual outcome were inscribed. This script is the earliest known writing in East Asia, and is the root of modern Chinese writing.

Oracle bone divination lost its popularity after the fall of the Shang dynasty in c.1050 BC, and over time seems to have been forgotten.

Almost 3000 years later, in the 19th century, farmers working near Anyang city came across piles of bones buried in pits. At some point, they came to become known as ‘dragon bones’, believed to have healing power.

They were sold to pharmacies and were ground into powder to use as ingredients in Chinese herbal medicines. It was not until the late 1800s that the true nature of the ‘dragon bones’ was recognised. In 1899 Wang Yirong, a prominent scholar who had studied ancient Chinese bronze inscriptions, was reportedly prescribed medicine containing ‘dragon bones’ when sick with malaria. Before the bones were ground up, he is said to have noticed the inscriptions and their similarity with those on bronze artefacts.

Research later confirmed it to be the earliest known form of Chinese writing, foundational to Classical Chinese – the language of scholarship, culture and administration across China, Japan, Korea and north Vietnam until the late 19th century.

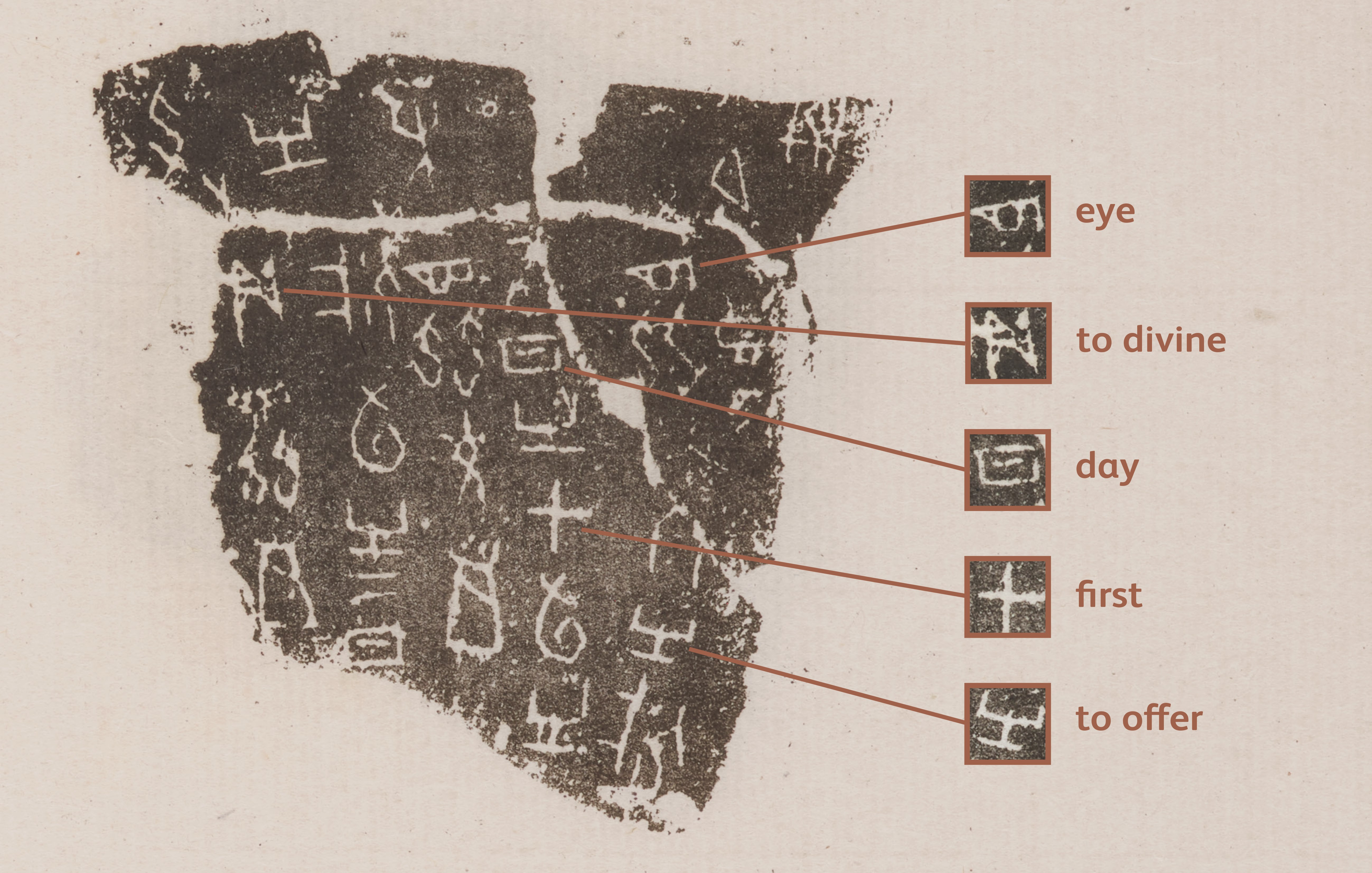

Ink rubbing from Tieyun Canggui, the earliest monograph on oracle bones (with illustrations overlaid).

Since the identification of oracle bones in the late 1800s, researchers have attempted to decipher their inscriptions. The carvings can reveal much about life in China during the Shang dynasty over 3000 years ago. They record important events, and offer glimpses of the lives and beliefs of the elite members of society.

The carved inscriptions also demonstrate a mature early writing system, with structured grammar and a range of characters conveying different meanings. Some characters are pictographs depicting shapes from the natural world, such as the character for deer. Others are more abstract, such as the number one, which is represented by a single horizontal stroke.

Today, the study of oracle bone script continues. Around 5000 individual characters have been identified, but only a third of these have been deciphered so far.

The excavation of a royal tomb at Yinxu in 1935.

The identification of the oracle bones led scholars to seek the place where they were originally uncovered. After much effort, this was finally confirmed as Xiaotun, a village within present day Anyang city, Henan province, in central China. Investigations eventually led to the first confirmed archaeological evidence for the site of Yinxu, the legendary last capital of the Shang dynasty.

Excavations began at the site in 1928 and have revealed a wealth of remains. As the capital, Yinxu occupied an area of about 30 km² and had palaces and temples, workshops, residential areas and cemeteries. Burials for the deceased were elaborately furnished as a form of ancestor worship. In 1976, the excavation of a burial of a queen named Fuhao yielded over 2000 items, including about 460 bronze and 750 jade objects.

Yinxu has been recognised as one of the most important archaeological sites in China and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.

Imitation of oracle bone of tortoise plastron of the late Shang dynasty (c.1200-1050 BC) from the Yinxu site, China.

Oracle bone of tortoise plastron or ox scapula, with incised script recording divination from the late Shang dynasty, c. 1200-1050 BC.

Bronze Banliang (half-ounce) coin from China, probably Qin dynasty (221–2016 BC).

Oracle bone of tortoise plastron with incised script recording divination from China, near Anyang, Yinxu, late Shang dynasty, c. 1200-1050 BC.

The Shang people used oracle bones to communicate with ancestors and deities, who were believed to have the power to bestow fortune, disasters and guidance on the living world.

At the royal court, the oracle bones divination was carried out by trusted ‘diviners’ or by the king and other members of the royal family. The king sought guidance on matters that concerned him, such as when the queen would give birth, the most auspicious time for a military attack, or the cause of a drought.

Detail of oracle bone showing a typical crack with inscribed characters

During a ceremony, prepared bones with carved grooves and drilled hollows were heated until they fractured into the desired shape. The fractures were believed to be the divine responses to the questions asked. Interpreting the cracks seems to be subjective and may have been used as a political tool to support the king’s wishes in the name of divine powers.

After a ceremony, inscribed bones were collected and periodically stored in pits as a form of royal archive. This direct access to the divine reinforced the king’s power.

The use of oracle bones for divination was part of the broader practice of ancestor and deity worship during the Shang dynasty. Many other artefacts have been discovered that show the importance of these beliefs to the Shang. Excavations have uncovered large numbers of jade, bronze and ceramic objects buried with the deceased, who immediately become ancestors with divine power. Evidence of human and animal sacrifice has also been found.

These rituals were intended to build a positive relationship with both ancestors and deities, encouraging them to send blessings and guidance to the living. The many rich artefacts in tombs and the cost of investing in ceremonies such as oracle bone divination also showcased the status and wealth of the dead and their living relatives.

Header image: Qin Cao, curator of Chinese collections, examines an oracle bone.