Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Home to over 90,000 species, Scotland’s land, seas and skies support a wide range of native mammals and birds, amphibians, reptiles and over 50,000 different invertebrates. The collection at National Museums Scotland has examples of some of the iconic, at risk and once extinct birds and mammals native to Scotland.

Scotland is a haven for wildlife, where you can see wild animals roaming free that are rare or extinct in the rest of Britain. Some of these are immediately recognisable and have become iconic symbols of Scotland. Red deer have become monarchs of the glen standing proud and majestic against the skyline. Seeing a red deer was once a rare occurrence, they are now a common occurrence.

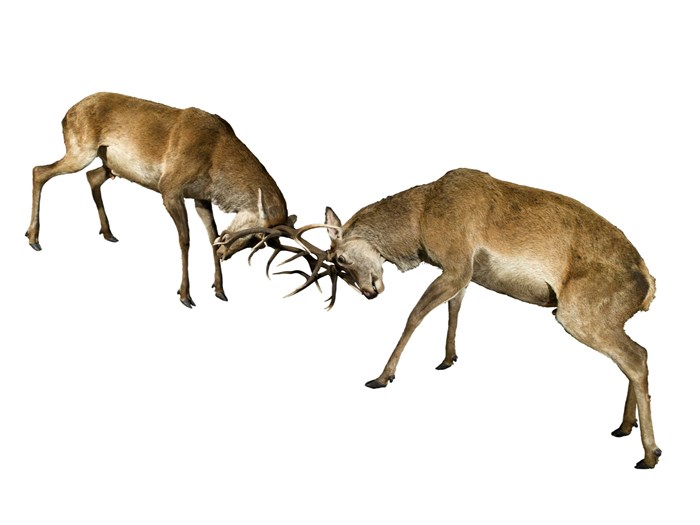

The Red Deer is the largest deer in the UK and is an unmistakable icon of the Scottish Highlands. During the autumnal breeding season, known as the 'rut', males roar to proclaim their territory and will fight over the females, sometimes injuring each other with their sharp antlers. A single calf is usually born the following spring. Red deer live on moorland and mountainsides, as well as grasslands near to woodland.

Two mounted Red deer specimens, fighting on Level 1 of Animal World at the National Museum of Scotland.

The changing seasons can bring about dramatic changes in animals’ habitats, especially it if snows. While brown colouration is perfect for matching many habitats, such as woodland, in summer, it makes an animal an easy target for predators against a white, snowy background. Many birds and mammals deal with this by moulting their fur or feathers in spring and autumn so that they can change colour to match their surroundings depending on the time of year. In most cases, either changing amounts of daylight or shifts in temperature trigger these moults.

Feathers and fur in animals are like human hair and fingernails -- they are actually dead tissue made from a protein called keratin. Consequently, a bird or mammal has to produce a whole new coat of fur or feathers in order to change its colour. Pigment granules in the fur and feather give them their distinctive colours.

Mountain hare on display at National Museum of Scotland.

Mountain hares live in upland areas and are most common on heather moorland. They are at their most visible in spring when the snow has melted but the hares are still white. They graze on vegetation and nibble bark from young trees and bushes. Hares shelter in a ‘form’, which is simply a shallow depression in the ground or heather, but when disturbed, can be seen bounding across the moors using their powerful hind legs to propel them forwards, often in a zigzag pattern.

They moult twice a year. In spring they moult into thinner brown fur, which camouflages them against hillside vegetation. In the autumn they moult into thicker white fur for insulation and camouflage against the snow

Ptarmigan on display at National Museum of Scotland.

Ptarmigan live in high mountains and change their plumage throughout the year to match their changing surroundings. In summer, it is a mixture of grey, brown and black above with a white belly and wings. In winter, it becomes totally white except for its tail and eye-patch, which remain black. The only place it is found in Britain is the Scottish Highlands.

Certain species that were once common in Scotland are endangered and are now protected by law. There has been exploitation of the Caledonian pine, deciduous forests, wetlands and peatlands and coastal and marine ecosystems. Intensification of agriculture and forestry and an increase in infrastructure associated with urban development has taken its toll and resulted in fewer numbers of some of Scotland’s native species.

The capercaillie is a huge woodland grouse and the large dark males are unmistakable. They are found in Scottish native pinewoods and in commercial conifer plantations. It became extinct in Scotland by 1785 owing to habitat loss and hunting, but the capercaillie was reintroduced from Sweden in the early 19th century. Sadly, the British capercaillie population has declined again so rapidly that it is at very real risk of extinction for the second time.

Hissing Scottish wildcat © Jack Barton photography.

Rarer than the tiger, the wildcat is Britain's last native cat species. Habitat loss, hunting and persecution led to its decline and it almost became extinct at the beginning of the 20th century. Wildcats are found in Scotland north of the Central Belt but used to occur throughout Britain. Hybridisation with feral domestic cats is the main threat to the survival of the wildcat in Scotland.

The wildcat is once again threatened with extinction and National Museums Scotland is one of the key partners of Scottish Wildcat Action which is trying to prevent its extinction.

Wild cat on display in Natural World at the National Museum of Scotland.

Red squirrels were once widespread throughout Britain. There are still many places you could encounter one today, from the conifer forests of Galloway, to the Atlantic hazel woodlands of Argyll, to the country estates of Tayside or the Caledonian pine forests of the Highlands. They may have almost become extinct in Scotland in the late 18th century owing to habitat loss, but several reintroductions, mainly from England in the 18th and 19th centuries restored populations here.

Red squirrels are threatened by the spread of diseases from the non-native North American grey squirrel and have been wiped out in many other parts of Britain.

Red squirrels feast mainly on seeds from pine cones in Scotland, They leave what looks like an apple core behind. Breeding begins in winter and carries on through spring. Females may have two litters of two to three young a year.

A red squirrel from the collection at National Museums Scotland.

Scotland's natural environment is constantly changing and wildlife that used to live in Scotland is now extinct. Some of these species have also become extinct due to human actions. Conservation organisations are hoping to reintroduce some species that were once native to Scotland including wolves, Eurasian lynx and brown bears following the successful reintroduction of beavers.

Wolf specimens at National Museum of Scotland.

The Eurasian beaver is the world’s second largest rodent. It was formerly native to Britain and once played an important part in our landscape until it was hunted to extinction in the 16th century. In 2009, the Scottish Beaver Trial released the first beavers to live wild in Scotland in over 400 years. This marked the first formal reintroduction of a native mammal species in Britain and launched a groundbreaking five -year study to explore how beavers can enhance and restore natural environments. From 1 May 2019, the Eurasian beaver was granted European Protected Species status in Scotland.

Beavers are herbivorous and do not eat fish. Their diet is made up of aquatic plants and grasses, as well as the bark, twigs and leaves of trees. Beavers live in small family groups and are thought to mate for life. Typically, two to four young, known as kits, are born each year. Youngsters will stay with their family for around two years, before leaving to find territories of their own.

Beaver in the wildlife diorama at the National Museum of Scotland.

The history of wild pig in Britain is complicated. A native species, they were hunted to extinction at some point in the Middle Ages. In the 1980s, boar farming became prevalent and many animals are believed to have escaped - or been illegally released – into the wild. A small population has been sighted at Loch Arkaig in the Scottish Highlands.

Wild pigs have stocky, powerful bodies with grey-brown fur. Mature males have tusks that protrude from the mouth. Piglets are a lighter ginger-brown in colour, with stripes on their coat for camouflage.

Wild pig in the wildlife diorama at the National Museum of Scotland.

Scotland is home to Britain's only free-ranging herd of reindeer, which were once native to Scotland. They became extinct thousands of years ago, mostly due to a warming climate after the last Ice Age.

The Cairngorm Reindeer Herd was established in 1952 and decades later the herd now stands at over 150 animals.

Reindeer are adapted for the cold and the conditions in the Cairngorm mountains suit them very well. They have thick fur coats with hollow hair to insulate them from the cold.

Reindeer in the wildlife diorama at National Museum of Scotland.