Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Metal mounts are nearly all that remain from Early Medieval drinking horns. We worked with a contemporary horn-crafter and designer to recreate these iconic drinking vessels.

Makers:

Johnny Ross, Sutherland Horncraft

Jennifer Gray, designer and maker

A Pictish stone from Bullion, Angus, shows a warrior on horseback holding a huge drinking horn with a large bird-headed mount at its tip.

As horn is an organic material and susceptible to decay, metal mounts are nearly all that remain from Early Medieval drinking horns. For example, we have two 9th century drinking horn fittings found in Scotland on display in Creative Spirit; a silver rim mount from Burghead, Moray and a tinned copper-alloy terminal mount from Pierowall, Westray in Orkney. Both of these mounts are the size which would fit locally available cattle breeds. However, metal fittings from exceptionally large horns have been found in high status Anglo-Saxon burials, including those at Sutton Hoo and Taplow in south-east England. 8th century Irish law tracts tell us that such large horns from wild cattle (aurochs) had to be imported into Britain and Ireland. The drinking horn that the Bullion man has clasped in his hands tells us that Pictish people probably had access to one of these imported auroch horns.

A Pictish stone from Bullion, Angus, shows a bearded warrior on horseback holding a huge drinking horn with a large bird-headed mount at its tip.

The Glenmorangie Research Project has worked with skilled horn-crafter Johnny Ross to recreate drinking horns based on this evidence. We have used two horns from the same beast of Scotland’s oldest breed, the Highland cow, and an imported horn of an ankole, a species of African cattle descended from aurochs. The Highland horns hold a pint of liquid, each enough for one person, but the larger horn holds a gallon, enough for communal drinking at feasts or heroic consumption to impress others. Through a painstaking process involving boiling, scraping, sanding and polishing, Johnny Ross brought out the glassy and translucent qualities of the horn. Each of the Highland cow horns were polished to different degrees. This revealed the various glistening and translucent material qualities of horn, evoking other high-status materials of glass and metal.

With the stunning backdrop of the Sutherland mountains behind him, Johnny is working on our specially commissioned African ankole horn recreation, based on the proportions of the Bullion Man stone. One of the smaller amber coloured highland cow horn recreations also sits waiting to be finished.

Inspired by the bird-head mounted on the end of the Bullion man’s drinking horn, we commissioned designer and maker Jennifer Gray to make a silver fitting for our African horn recreation. White-metals were preferred by the Picts for making high-status fittings. As with all of our recreations, the piece evolved through constant dialogue with the evidence, on-going research and the maker’s specialist crafting and material know-how.

We provided Jennifer with a palette of inspirations including the Ninian’s Isle chapes, Norrie’s Law hoard and the Rogart brooch.

(Left to right) Ninian’s Isle chapes, Norrie’s Law hoard and the Rogart brooch.

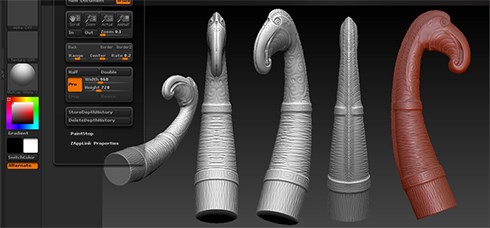

Jennifer used a unique combination of innovative 3D technology and traditional silver-making methods. The mount was “virtually” carved in a 3D digital design programme, “like you would by hand but by using a mouse”. This was then 3D printed, cast into wax and carved into by hand. This wax end-piece was then cast in silver.

Jennifer Gray’s work connects the different digital and traditional methods of recreation used by the Glenmorangie Research Project; there is always a tension between authentic craft techniques available to the Early Medieval people and new innovative technologies available to us today. New and old ways of doing can help us understand Early Medieval objects and the skills required to make them.

Jennifer's digital reconstructions of the fitting for the horn.

Jennifer Gray and Johnny Ross with the completed horns in the Creative Spirit exhibition.