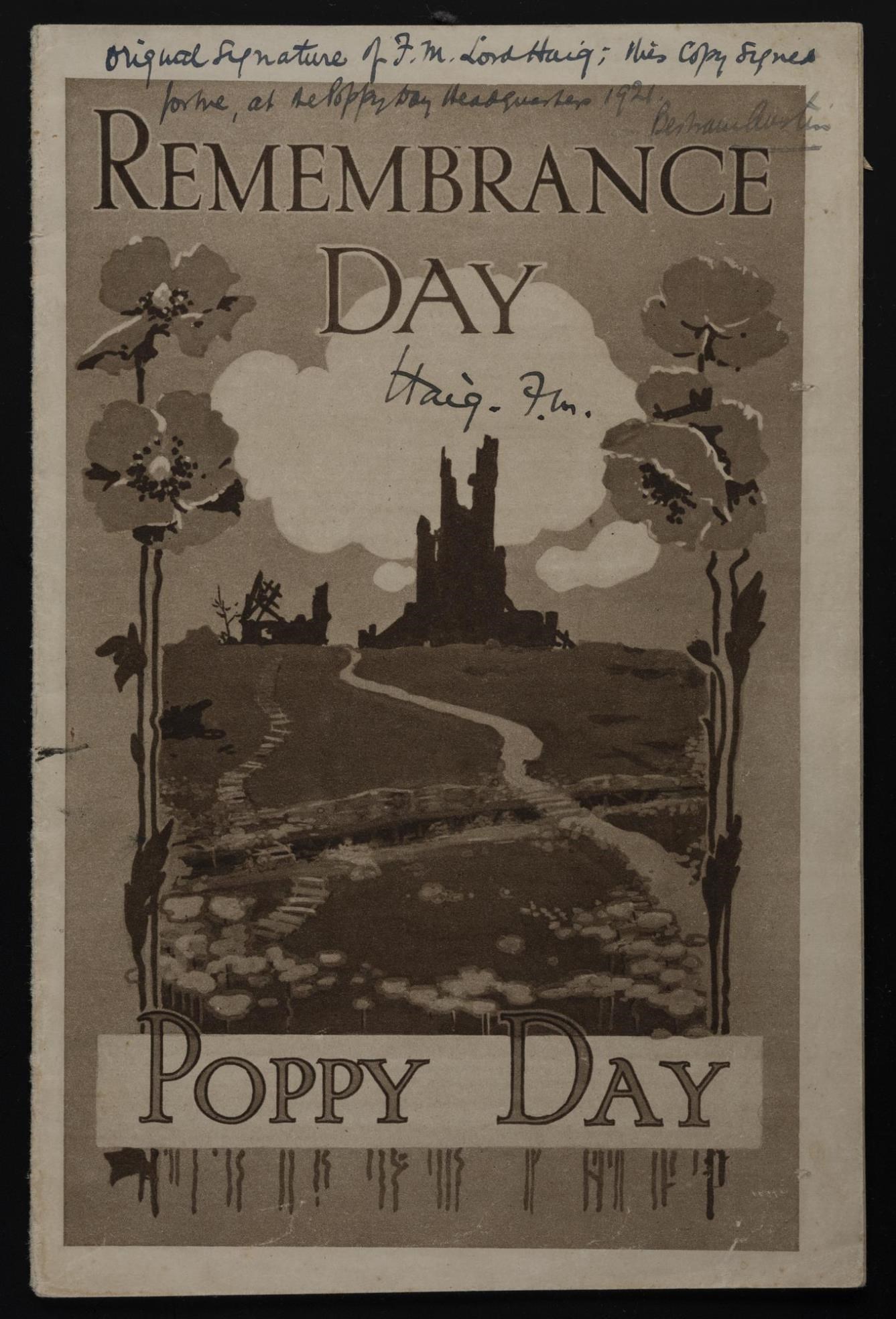

1921

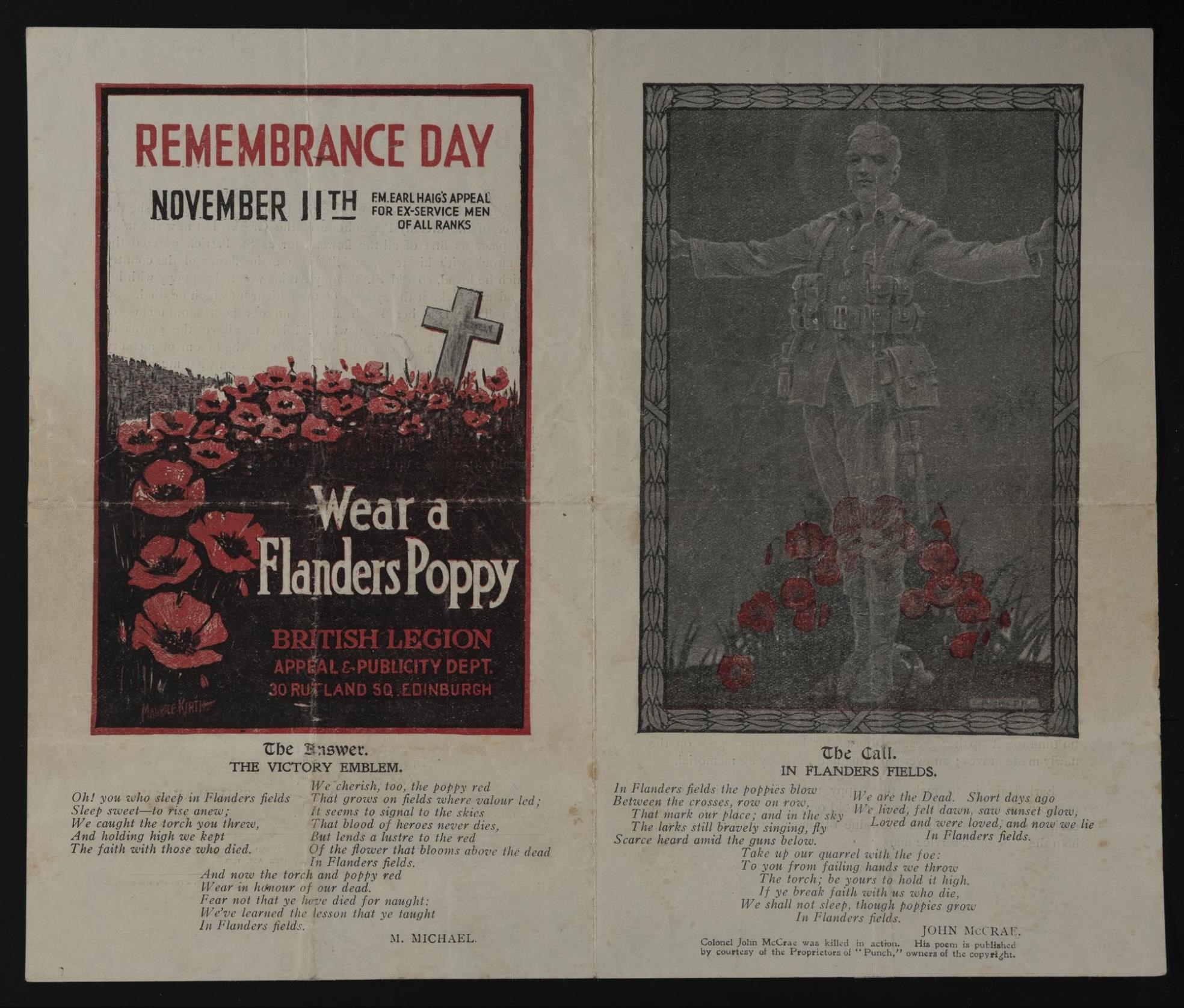

Anna Guerin showed examples of her handmade poppies to the newly-formed British Legion in London. The President of the British Legion was Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig of Bemersyde, the former commanding officer of the British Army on the Western Front.