Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

James VI and I was a hugely significant Stewart king, but has been overshadowed by his notorious relations: his predecessor in Scotland, his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots; in England, his cousin, Elizabeth I; and his successor in both kingdoms, Charles I.

James VI and I was a hugely significant Stewart king, but has been overshadowed by his notorious relations: his predecessor in Scotland, his mother, Mary Queen of Scots; in England, his cousin, Elizabeth I; and his successor in both kingdoms, Charles I.

Above: James VI and I after he had acceded to the throne and moved to London. Bequeathed to National Galleries Scotland by Sir James Naesmyth 1897. Image courtesy of National Galleries Scotland.

Born in 1566, he was the product of Mary’s ill-fated marriage to Henry, Lord Darnley. Darnley’s assassination in early 1567, and Mary’s subsequent over-hasty marriage to one of its perpetrators, Lord Bothwell, triggered events that led to Mary’s downfall.

Above: Engraving of Mary Queen of Scotland with her son (later James VI and I), after a painting by F. Zucherri, published 1779.

James VI became king of Scotland in 1567 when Mary was forced to abdicate. On the death of Elizabeth in 1603, he became James I of England. He is thus known as James VI and I.

In 1590 he married Anna, the sister of the Danish king, Christian IV. They had numerous children, three of whom survived infancy: Henry, who died after a short illness in 1612, Charles who was to succeed James, and Elizabeth, who married Frederick, elector of Palatine, and the swiftly deposed King of Bohemia. Romantically she has become known as the Winter Queen.

Above: Anne of Denmark, by an unknown artist. Bequeathed to National Galleries Scotland by A.W. Inglis 1929. Image courtesy of National Galleries Scotland.

Unlike his mother or his son Charles, James died of natural causes in his own bed in 1625.

James was one of the most long-standing monarchs of Scotland, king for 58 years from the age of one. Of the Scottish monarchs before the Anglo-Scottish union of 1707, only William the Lion (1165–1214) comes close in longevity.

But he is notable not just for the length of his reign, but for the amount that he managed to achieve within it.

Of these achievements, perhaps the most significant of all was his careful management of his peaceful succession to the English throne in 1603. In doing so, he brought the ‘auld enemies’, the kingdoms of Scotland and England, together under the kingship of one monarch. This dynastic or regnal union became known as the ‘Union of the Crowns’, which included that of Ireland too. In 1604, James proclaimed himself King of Great Britain. So James’s reign produced the first Anglo-Scottish union (though this was not full political union) which helped to form the background to the formal union of 1707.

In 1567, at the age of one, James was placed in Stirling Castle for his care and safety. Following a visit to see him, Mary was ‘abducted’ by James Hepburn, Lord Bothwell (whether or not she was a willing participant is unknown) and forced into marriage to him. This visit proved to be the last time James ever saw his mother.

Above: The Penicuik jewels. This locket is said to show Mary, Queen of Scots and her son James on the reverse. The Clerks of Penicuik had a connection with Mary through marriage. In the 17th century, a member of the family married a granddaughter of Giles Mowbray, one of the Queen's servants during her English imprisonment. It is possible that the necklace is made from the beads of bracelets given by the Queen to Giles Mowbray, just before her death in 1587.

Over the next twenty years they had a difficult relationship – hampered by the physical distance between them, the problems of communication by letter or word of mouth, and dependent on who had custody of the young king – and most importantly, tensions over Mary’s attempts to regain her Scottish throne during her English captivity. Mary’s return would have compromised James’s own kingship. Famously, James did little other than protest to Elizabeth over Mary’s execution in 1587.

James ordered a splendid tomb to be made for Mary in Westminster Abbey when he became king of England. Mary’s marble tomb with its elaborate canopy outshines the one he created for his predecessor on the English throne, Elizabeth I. In death you could say that Mary triumphed over the queen that had signed her death warrant, and in memorialising Mary in such a way, James perhaps assuaged any guilt he may have felt. Given her claim to the English throne (as a great-granddaughter of Henry VII), Mary would have thought it fitting to be laid to rest alongside other English monarchs.

Plaster cast of the tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots.

As an infant, James had councillors ruling in his name, but he took up his personal reign in his mid-teens, in the early 1580s. His childhood was spent at Stirling castle in the care of Annabella, Countess of Mar, whose son became a lifelong friend of the king. He was tutored by the stern Presbyterian and humanist George Buchanan.

Above: James VI as a boy, by an unknown artist. David Laing bequest to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, gifted to National Galleries Scotland in 2009 and on loan to the National Museum of Scotland. Image courtesy of National Galleries Scotland.

Above: Cradle said to have been that of Mary, Queen of Scots at Linlithgow Palace.

James was a clever boy, very well educated, who learnt the art of argument early. In 1579, aged, 12, he made a formal entry as king into Edinburgh. But in the years following he suffered from political and religious factionalism at court, and in 1582 was abducted in the Ruthven Raid by several nobles, including the earl of Gowrie, who wanted to ensure a Presbyterian-inclined government of Scotland.

By 1585, however, James was old enough to begin to impose his own will on the feuding factions.

James had strong views on the rights of kings. His tutor Buchanan’s book De Jure Regni had called for a contractual monarchy in which kings can be held to account for their actions. This was an attempt to legitimise the overthrow of James’s mother Mary. James was subsequently to publish a rebuttal, The True Law of Free Monarchies, which set out an opposing opinion on the duties of the subject to the king, and vice versa. He saw himself as one of God’s lieutenants on earth, and thus his power was the result of divine will, and not to be argued with.

Above: Articulated figure of James VI on the throne. A lever at the back moves his arm which may have once held a sceptre.

Above: Front of James VI gold 20-pound piece, Edinburgh, 1575.

Above: Reverse of James VI gold 20-pound piece, Edinburgh, 1575.

James was also renowned for having favourites at court. Because these men exerted significant power they stimulated resentment amongst those less favoured.

These close relationships have led to speculation that James was gay, although it would be difficult to prove this conclusively.

Above: Watch thought to have been given by James to the earl of Somerset: his principal Scottish favourite at Whitehall was Robert Ker from near Jedburgh, whom James ennobled as the earl of Somerset. Somerset was implicated in a political murder and in 1615 fell from grace.

Above: Stained glass panels of James and the duke of Buckingham: the English George Villiers soon replaced Somerset in James’s affections and was speedily elevated to the peerage. He was to remain one of the king’s closest advisers and accompanied the young Prince Charles on his fruitless journey to Spain in search of a royal bride.

The Protestant Reformation in Scotland created a more Calvinist version of Protestantism, known in Scotland as Presbyterianism, in which all participants were said to be equal. James’s relationship with the kirk was somewhat fractious. Although he was a committed Protestant, he believed in a less extreme, Episcopalian version of Protestantism, in which the king was the head of the church, and ruled it through bishops. His idea of the church’s role more closely resembled that of the English Anglican church. An infamous incident occurred in 1596 when a Presbyterian minister, Andrew Melville, shook the king by the sleeve calling him but ‘God’s silly vassal’ in the religious sphere.

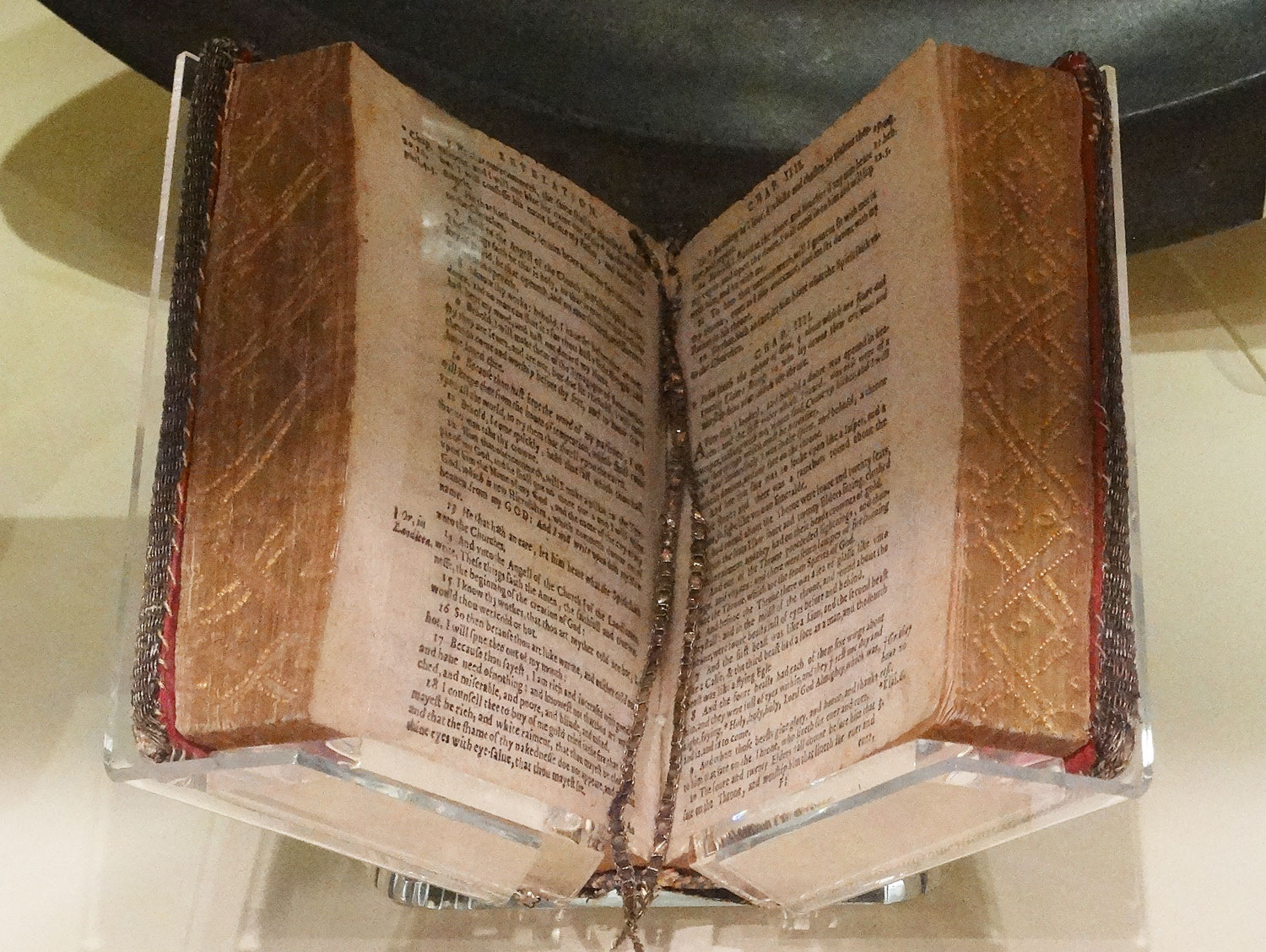

James’s ecclesiastical legacy endures in the King James Bible of 1611, which he commissioned.

Above: New Testament of 1619: New Testament (London, by Bonham Norton & John Bill, 1619) and Psalm book (London, 1621) bound together and covered with silver and silver-gilt threadwork and multicoloured petit point embroidery.

In 1590, James married Anna, the sister of the Danish king, Christian IV. After a rough crossing of the North Sea, she received a grand formal entry into Edinburgh. She was a powerful figure in her own right, and maintained good relations for Scotland with the rich Protestant Danish king.

Above: Silver medal struck for James’s marriage to Anna in 1590.

Above: Church-ship model said to have been built in celebration of James and Anna’s marriage, and may have hung in a church in South Leith.

In 1590, as James was attempting to bring home his new Danish wife Anna, a storm blew his ship off-course near the coast of East Lothian. Subsequently, several alleged witches from North Berwick were arrested, tortured and executed, a process in which James took an active part. For a time, he was obsessed with uncovering witches, and in 1597 published a tract on them, Daemonologie.

Above: Witch's iron collar or jougs formerly owned by the parish of Ladybank in Fife, 17th century. You can read more about this object here.

James was determined to assert his power as king, and to crack down on the ancient custom of bloodfeud. These violent disputes between families, and their large armed retinues, were often very long-running. Bloodfeud was seen as especially prevalent in the Borders (though it happened throughout Scotland), and James was to target the feud there. This was also part of his suppression of violence and cross-border raiding in the late 1590s, when it looked likely that he would succeed Elizabeth on the English throne.

The most famous of the Borders’ feuds was that between the families of the Scotts and the Kers.

Above: An iron morion helmet known popularly as a ‘steel bonnet’, headgear of the Border raiders. This was found at Ancrum, a stronghold of the Kers.

Above: Wat o’ Harden’s horn: Walter Scott of Harden was one of the leading men of the Scott surname, and deputy to its head, Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch. He would have used this bugle to call his men to his side in a raid or skirmish.

Above: Wat o’ Harden’s spurs: reputedly, when the cupboard was bare, Harden’s wife used to serve these spurs for dinner, to ask the men to go and find food.

In 1603, James VI succeeded to the English throne on the death of his cousin Elizabeth I with no direct heirs. As the new James I of England, he rode south and was to spend almost the entire rest of his life in England, based at Whitehall. He is thus known to us as James VI and I. James was very keen to promote the idea of union and friendship between the previously hostile England and Scotland. He called it a ‘blessed union’, one of ‘hearts and minds’.

Above: Banner showing James VI and I’s coat of arms combining those of Scotland (the saltire, the unicorn, and the rampant lion in the top left dominant quarter), of England (the cross of St George, the three lions in the top right quarter), and of Ireland (the harp in the lower left quarter).

Despite promising on his departure to return every three years, James was only to return to Scotland once in 1617. Having professed a ‘salmon-like’ desire to return to the land of his birth, he came with a multitude of English and Scottish courtiers and councillors, and spent around three months touring his castles and palaces, and those of the great lords and lairds.

Above: Ceiling boss of carved wood, with a unicorn carrying a Union flag, with traces of original paintwork, from Linlithgow Palace, Scotland, c. 1617.

During this period, he presided over a meeting of the Scottish parliament, which famously rejected his attempt to get them to pass his ecclesiastical reforms, which became known as the Five Articles of Perth. Elite Scottish households prepared for the king's visit and there are several examples of objects and decoration made in case the king came to visit.

Above: Circular beech box containing a set of fourteen roundels or plates used at an entertainment given by Sir George Bruce of Carnock for King James VI: English, 1570 – 1620, with inscription on the bottom, ‘Desert Plates used at an Intertainment given by George Bruce of Carnock to King James 6’. James and his retinue visited the successful entrepreneur Sir George Bruce at his newly built ‘palace’ at Culross. Bruce was famed for his coal mine which reputedly ran for a mile under the Firth of Forth. James took fright on his tour, popping up in the middle of the firth to be rescued by boat.

James died in 1625 and was succeeded by his son, Charles. You can read more about Charles here.