Decoding a portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh

News Story

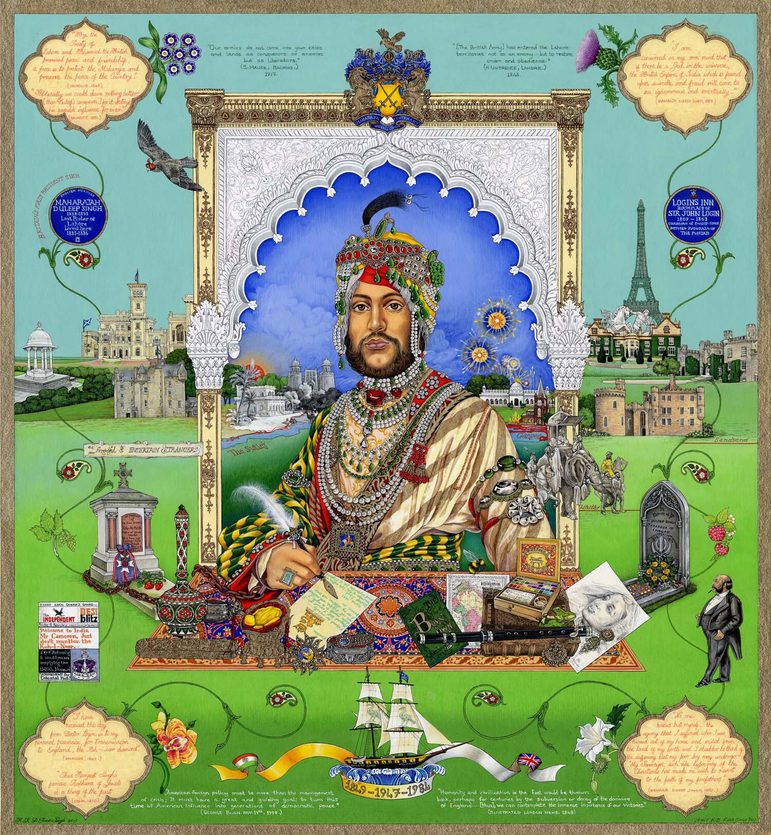

‘Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh’ is a painting by renowned British Sikh artists The Singh Twins. As the last sovereign ruler of the Sikh Kingdom, Maharaja Duleep Singh (1838-1893) was deposed from the throne by the British East India Company and exiled to Britain.

Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh, by The Singh Twins, poster paint and gold dust on mountboard, 2013.

Maharaja Duleep Singh

The painting was created as a response to items in our collection which belonged to the Maharaja. Meticulously rendered in all their details, the painting highlights the connection of these items to one of the most important figures of British Sikh history.

Image gallery

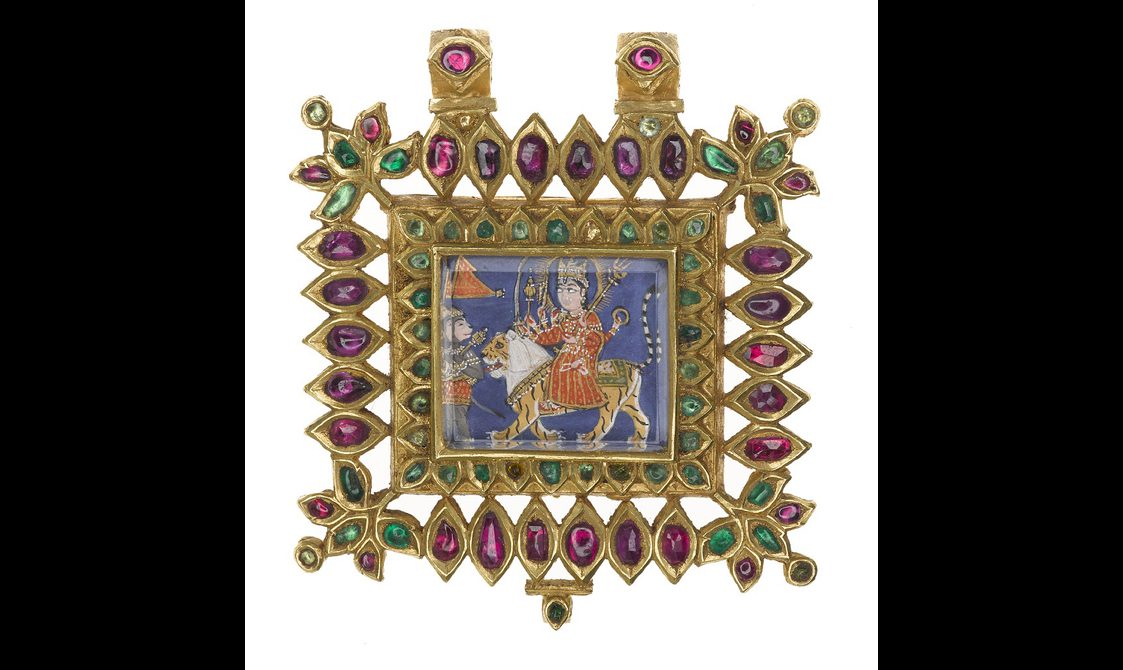

Pendant of gold, set with rubies and emeralds, underneath a large rock crystal in the centre an image of the Hindu goddess Durga riding on a lion-tiger, northern India, 1800-1850. Depicted in the painting attached to the pearl necklace.

Armlet of gilded silver, flower-shaped, the front set with large rock crystals, the back with an enamelled flower vase, northern India, possibly Jaipur, 1800-1850. Depicted in the painting around the Maharaja’s left arm.

Rosewater flask of gold with green, red and blue enamels, northern India, possibly Jaipur, 1800-1850. Depicted in the painting on the left in front of the Maharaja.

Pen case of gold, chased all over with scrolls, flowers and leaves, northern India, 19th century. Depicted in the painting on the left in front of the Maharaja.

Antimony holder of nielloed silver decorated with floral patterns and bird-shaped stopper, possibly India, 19th century. Depicted in the painting on the left in front of the Maharaja.

Pair of ear ornaments, likely to have belonged to Maharaja Duleep Singh’s mother, Maharani Jind Kaur, northern India, 1800-1850. Depicted in the painting attached to the portrait of his mother on the right in front of the Maharaja.

Bracelet, one of a pair, with makara-heads, enamelled and set with rubies, emeralds and a diamond, northern India, late 18th - early 19th century. Not depicted in the painting.

Box of gold for betel in the shape of a buta, the lid decorated with a floral pattern in chased and open work, northern India, 19th century. Not depicted in the painting.

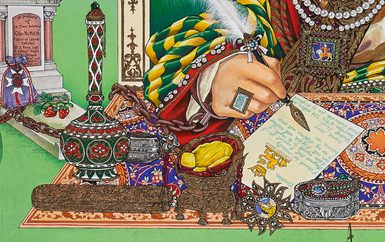

Duleep Singh is depicted in all his splendour as the artists imagined him in his rightful position as Sikh ruler of Panjab. He wears the Sikh turban, the royal seal ring, and the imperial black plume of kingship.

He is adorned with some of the most famous jewels: a ruby necklace, an emerald belt, and, around his left arm, the legendary oval-shaped Koh-i-Noor diamond, the ultimate symbol of sovereignty and power. They were once kept in the treasury at the court in Lahore.

We pick out seven details from the painting to understand their historical meanings and contemporary connections. This interpretation is based on The Singh Twins’ Artists’ Commentary, 2014 and research by Friederike Voigt, Principal Curator, West, South and Southeast Asian collections, on Maharaja Duleep Singh’s possessions in our collection.

1. Early life in Lahore

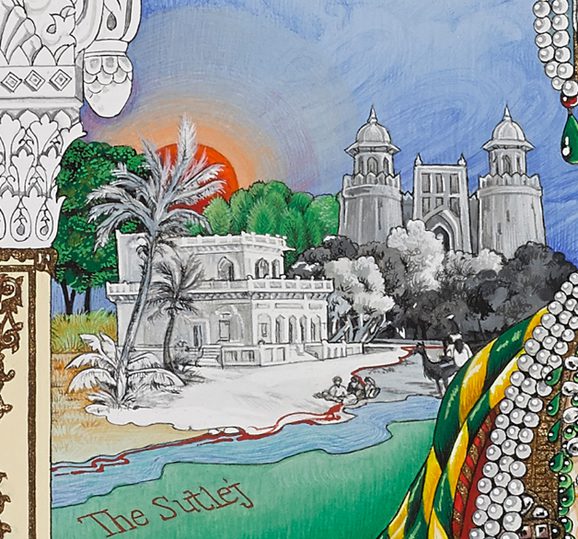

The huge gateway of Lahore Fort and the garden pavilion in the foreground recall the places of Duleep Singh’s childhood. The garden of Hazuri Bagh was laid out by his father, Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The Sutlej River marked the border between the Sikh Kingdom and the territory controlled by the British in India. The East India Company’s army crossed the river when invading Panjab in 1848. The river symbolises the end of Sikh sovereignty as does the setting sun behind the trees. However, the sun can also be understood as rising, indicating the expansion of the British territory in India.

The Sutlej River is stained red to remember all those who died during the two Anglo-Sikh Wars.

Early life in Lahore, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

2. In exile

The military town of Fatehgarh was the first exile for the deposed Maharaja. The joyful fireworks in the sky carry an ambiguous message. For 11-year-old Duleep Singh, Fatehgarh was a place of sorrow, away from his home and people.

The elegant white building in the background was the house of John Login, his guardian. Login had been appointed by the Governor-General of India, the Marquess of Dalhousie, to take care of the Maharaja who was still a minor.

Duleep Singh lived in a separate bungalow. It is not depicted as it was destroyed during the Indian Uprising in 1857-58. So was the red stone church in the foreground, which was rebuilt, however. The flames next to it and the blood in the river Ganges hint at this fight of Indians against British rule and oppression. By this time, Duleep Singh was in his second exile in Britain.

In exile in Fatehgarh, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

3. The Sikh treasury at Lahore

The oblong gold pen case, enamelled rosewater flask, and bird-shaped silver container are amongst Duleep Singh’s personal possessions in our collection. Moreover, two pieces of jewellery feature in his attire: a square pendant that he is wearing on a pearl necklace and the flower-shaped rock crystal ornament around his left arm. The artists cleverly incorporated his mother’s portrait into the composition, adding an ear ornament which likely belonged to her. All these pieces were sold by his son and heir Prince Victor at an auction in London.

Other pieces from the Lahore treasury include Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Golden Throne, his Order of Merit, and a turban ornament displayed on top of an ornate silver box. As the throne was associated with the sovereign power of the Sikh Kingdom, the East India Company sent it to Britain after their victory in 1849. It is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Jewellery from the Lahore treasury, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

Jewellery from the Lahore treasury, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

4. A British gentleman

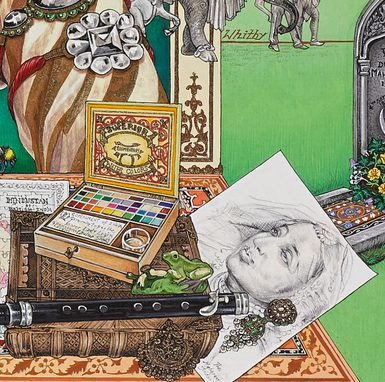

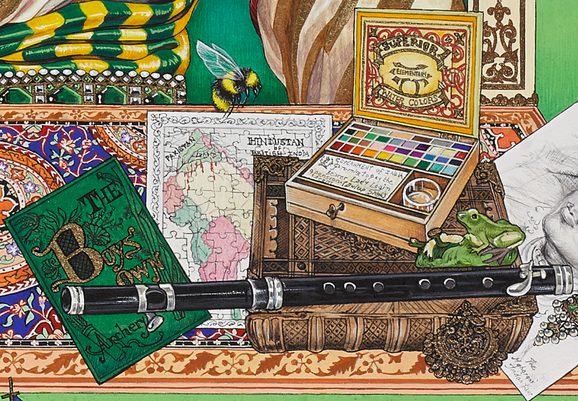

While still in India, Duleep Singh was educated in the faith and values of Victorian society to prepare him for an aristocratic life in Britain. The objects displayed on the right-hand side in front of him refer to the different subjects he was taught. He continued to study Urdu and Persian but also commenced to learn English. The ‘Boy’s Own’, a British magazine to shape ideals of masculinity, was amongst his readings. He also began to play the flute.

Lena Login, his guardian’s wife, sent him a paint box, geographical puzzles, and mechanical toys (frog) from England for his amusement.

It was also in Fatehgarh that he converted to Christianity. This is symbolised by the antiquarian book which is a copy of the bible. The Marquess of Dalhousie presented it to Duleep Singh on his departure from India in 1854.

A gentleman's education, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

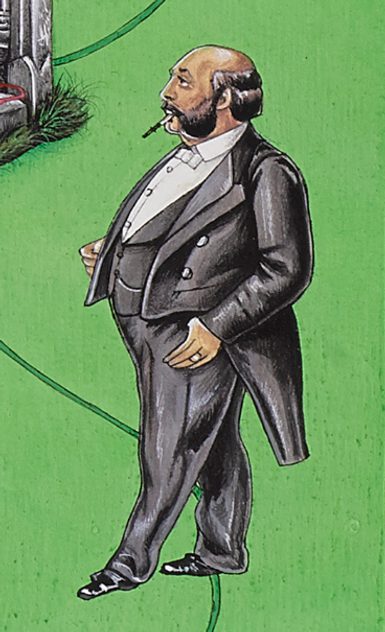

5. A life of two cultures

Several elements in this painting highlight Duleep Singh’s dual identity. His standing figure in western attire is a copy of a caricature by the artist Spy. Duleep Singh’s diminished stature represents him as the ‘tamed’ English Christian gentleman, the role which the British establishment wanted him to assume.

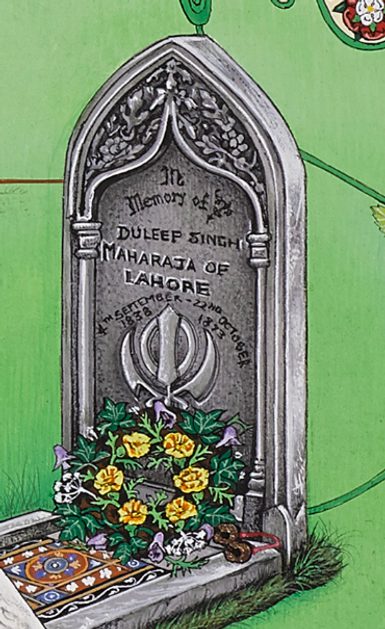

However, Duleep Singh held on to his Indian roots. Though he re-embraced Sikhism later in his life, on his death, he was given a Christian burial. In this way, the British government reasserted their power over him. As a reminder of Duleep Singh’s struggle, the artists added a Khanda, the emblem of Sikh religion, to the headstone of his grave.

The Maharaja in western attire, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

Headstone of the Maharaja's grave, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

6. Sir John Login

John Login joined the East India Company as a military surgeon. Following the annexation of the Sikh Kingdom by the Company in 1849, he was appointed as the deposed Maharaja’s guardian. It was no easy task, as he took a fatherly interest in Duleep Singh. More than once he had to be reminded that in the first instance, he was a servant of the British Crown.

Duleep Singh grieved deeply when Login died unexpectedly in 1863. He had a monument erected over Login’s grave, acknowledging the tender care with which he had watched over him as a child. The artists express the ambivalence of their relationship through the heavy chain that leads from Duleep Singh’s wrist to Login’s memorial stone.

Sir John Login's grave, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

7. Britain's first resident Sikh

Maharaja Duleep Singh and his life story continue to be relevant today. Considered to be Britain’s first resident Sikh, he has become a central figure of identity for Sikhs in Britain and around the world. Charitable initiatives associated with his name seek to advance public knowledge of Sikh history, culture and religion in Britain.

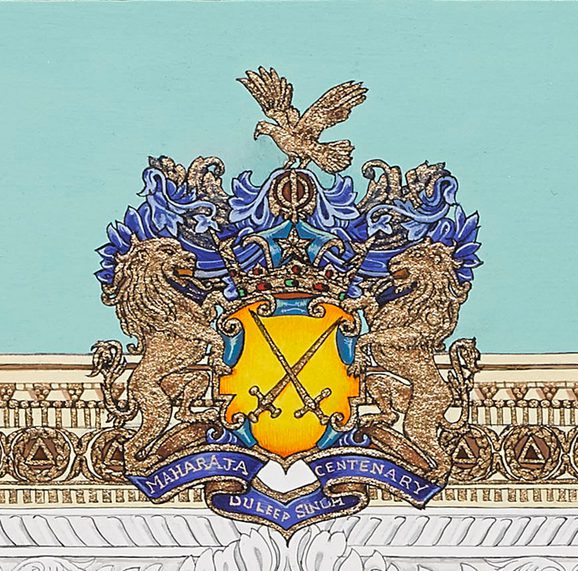

In 1993, the Maharaja Duleep Singh Centenary Trust commissioned a coat of arms to mark the 100th anniversary of his death. Its shield of two crossed swords is supported by a lion on either side. A Khanda surmounts the royal crown representing him as the lawful Sikh ruler. When a statue of the Maharaja was erected in Thetford, England in 1999, the coat of arms was placed above the commemorative inscriptions.

Commemorative coat of arms, a detail from Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh.

The painting ‘Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh' (museum reference V.2013.31) is on display in the Artistic Legacies gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.