A history of ancient Egyptian shabtis in 11 figures

News Story

Ancient Egyptian shabtis will be familiar to many museum-goers. Their iconic shape, portable size, and variety made them highly collectable in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Shabtis are one of the few types of ancient Egyptian objects that Egyptologists describe using their indigenous name. Shabti originates from šwbty ‘shawabty’ and wšbty ‘weshebty’. Šwbty was the original ancient Egyptian name for these figures and means something like 'stick', while the later name wšbty means 'answerer'.

Initially, single figures were placed in burials to act as a substitute for the dead person, sometimes with their own miniature coffin. Later, as Egypt engaged in greater international trade, empire building and increased production at home, the shabti became a representation of agricultural workers. Worker shabtis could be magically activated by the owner to undertake work for them in the afterlife. This led to an increased number of figures being produced to represent teams of labourers. This change in purpose may be reflected in the shift in the name for these figures, from stick to answerer. It seems probable that answerer originates from the inscribed spells on many shabtis which asked the figure to answer (‘wesheb’) when called and go to work for the owner in the afterlife.

Though today we group them together, these shabtis were used in burials across 2,000 years. Over time they varied in size, design, material, inscriptions and function.

Shabtis can tell us lots about ancient material culture, the people who owned them, and the archaeologists and collectors who excavated or bought them in Egypt.

1. Early Shabtis

Around 2,000 BC we see the early development of shabtis. The earliest shabtis were made of wood or wax and were often contained in a model coffin. They were probably intended to act as a substitute for the owner if they were called upon to do forced labour in the afterlife. Burials of the following centuries could include a single shabti figure. Th example below shows a black serpentine stone shabti belonging to a man named Deduhor. He holds a divine sceptre and ankh-symbol – symbols of power, life, and eternal protection. Deduhor is shown with large ears, copying the style of royal statuary popular at the time.

Black serpentine shabti shown holding an ankh and was-sceptre, with a dedication naming the owner as Deduhor: Ancient Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, possibly Edfu, 12th-13th Dynasties, c.1985-1650 BC. Museum reference A.1965.21.

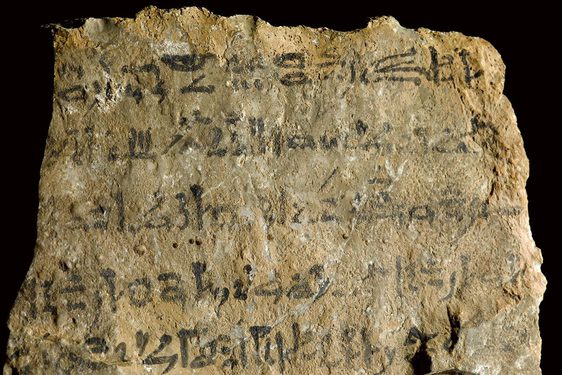

2. Inscribed shabtis

Most shabtis include the name of the owner in their inscriptions. This was partially so that they could be identified as that person’s property, but also because the preservation of a person’s name was important in Egyptian funerary beliefs.

Some shabtis were made with gaps in the inscription, ready for the buyer’s name to be added in. This was also done with other funerary objects such as papyri. This wooden shabti has a noticeable addition to the inscription, but it is not an example of a purchase from an undertaker’s stock. Instead, we can see that a previous owner’s name was erased and written over with the name of man called Ramessesnakht. If you look closely at the left-hand side of the first line of hieroglyphs, you can see a blue inky shadow of the original name.

Shabti in painted wood, with an inscription in five lines naming Ramessesnakht, the writing of the name indicates reuse of an older shabti: Ancient Egyptian, New Kingdom, 19th - 20th Dynasty, c.1295 -1069 BC. Museum reference A.1934.565.

3. Overseer shabtis

From around 1295 BC, burials slowly began to include greater numbers of shabtis. This led to the increasing popularity of more affordable and easily workable materials. Faience, a glass-like paste could be fired to produce a brilliant blue-green copper glazed ceramic.

An Egyptian year was 365 days long and around 1069 BC, sets of shabtis expanded to this number. Sets began to include overseer shabtis. Overseer shabtis like this example carry a whip rather than agricultural tools, to ensure that the shabtis carried out their work. These overseer shabtis were given the title ‘chief of the ten’ as they each supervised ten workers, one for each day of the Egyptian week.

Shabti of an overseer in bright blue glazed faience, with no inscription: Ancient Egyptian, 3rd Intermediate Period, 21st - 22nd Dynasty, c.1069–715 BC. Museum reference A.1921.850.

4. Royal shabtis

Royal individuals also had shabtis. This example is inscribed for King Seti I who reigned c.1294-1279. His tomb is one of the longest and deepest in the famous Valley of the Kings. It was first explored by Europeans in 1817 when the engineer, collector and former circus strongman Giovanni Belzoni entered its highly decorated rooms.

In his popular account of his adventures, he described using small ‘wooden figures…covered in asphaltum’ as handy fire torches to light the space. He was clearly using the juniper wood shabtis covered in organic resin that he had found in the tomb, like this example. It is estimated that King Seti I may have had nearly 1000 shabtis in his burial made from wood, stone and faience.

The sheer number of these shabtis has meant that they have become spread across the world. Several Scottish Museums care for shabtis of Seti.

Juniper wood shabti inscribed with a shabti-spell in favour of King Seti I, with traces of black resin: Ancient Egyptian, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Valley of the Kings, KV17, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, c.1294-1279 BC. Museum reference A.UC.59.4

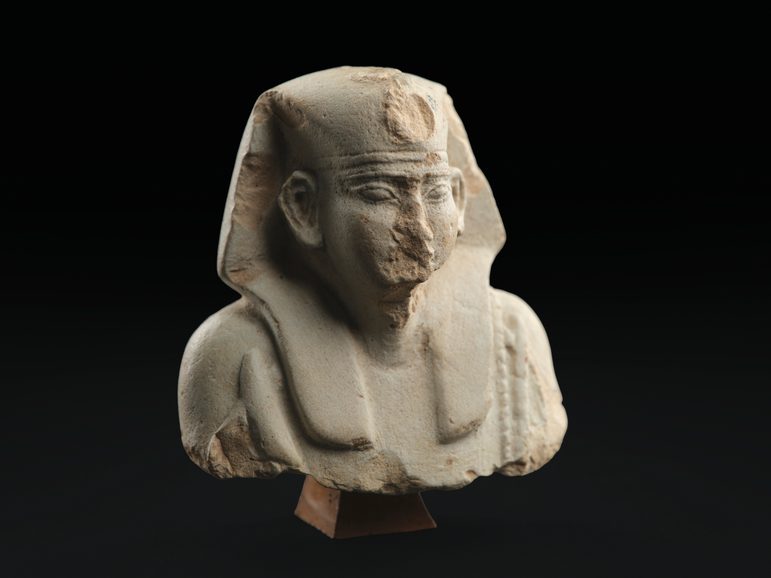

5. A fragment from a missing tomb

Some ancient objects in museum collections give us clues about unlocated monuments and tombs. This fragment of a royal shabti probably belonged to King Psamtek I (c.664-610 BC) whose tomb is not currently located. This shabti was identified by shabti expert Glenn Janes in 2024. Janes noted that the specific style of the king’s headdress and the rope bag he carries over one shoulder that are attested in other known shabtis of that ruler.

Upper part of a faded faience royal shabti depicting the king wearing a nemes-headdress with a broken uraeus, probably King Psamtek I: Ancient Egyptian, Late Period, 26th Dynasty, c.664 - 610 BC. Museum reference A.1965.19.

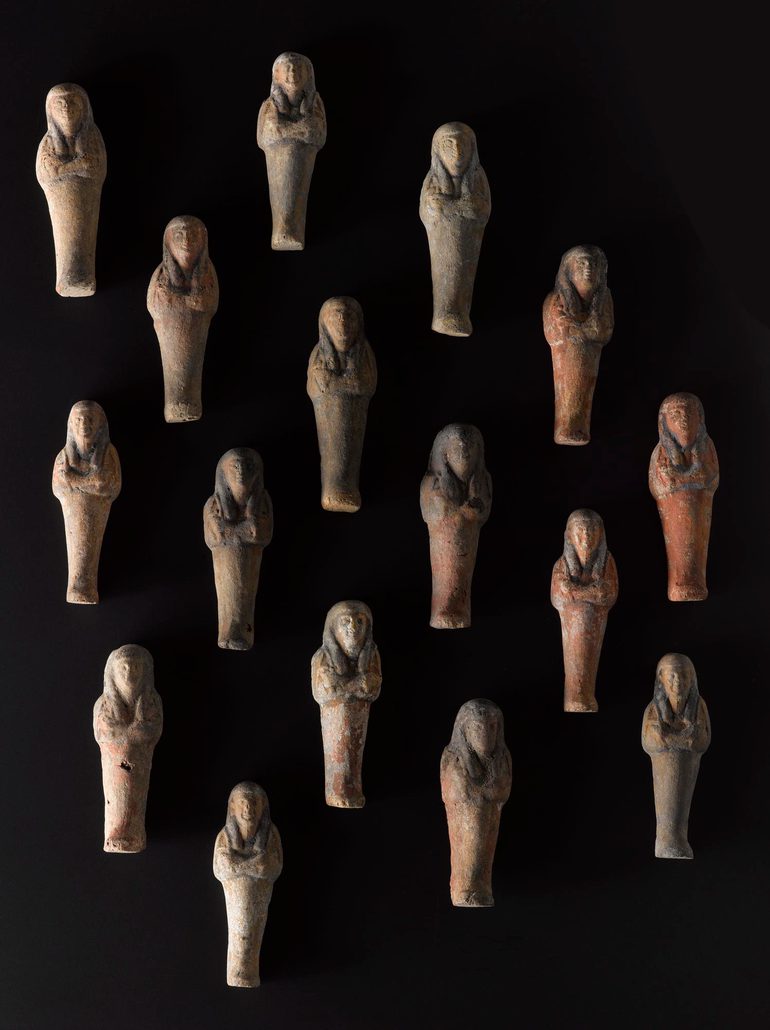

6. Groups of shabtis

The major changes that took place in the size, shape, decoration and material of shabtis help Egyptologists date them. This in turn can date the burials in which these shabtis are excavated. For example, if the figure is wearing a seed bag over their left shoulder, then we know they were manufactured after around 750 BC. If they are wearing a hairband then they date to between around 1100 and 750 BC.

The pioneering Scottish archaeologist Alexander Henry Rhind used the group of shabtis below and other funerary objects found in a single tomb to track and date its re-use over time. The size, shape, material and number of these shabtis can tell us that they were made around 747 - 656 BC.

Sixteen pottery mould-made shabtis, contained in a rectangular wooden shabti box: Ancient Egyptian, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Third Intermediate Period, probably 25th Dynasty, c. 747 - 656 BC. A.1956.286 B.

7. Royal reburials

During a period of social and economic upheaval in c.1100-900 BC, there was an increase in tomb robbery targeting royal burials in the Valley of the Kings. To safeguard their bodies, priests from the Temple of Amun moved dozens of royal individuals to a more hidden tomb. Several family members of the High Priest of Amum Pinudjem II were also buried there. Nestanebasheru, the owner of this shabti, was one of his daughters.

This burial cache, known as DB320, became publicly known in 1881 after objects from it began entering the local art market. To stop this trade, the Egyptian Antiquities Service rapidly cleared the tomb over two days, recording little information about the position of the objects in it. Because a high number of shabtis and other ‘duplicate’ objects were emptied from the tomb, many were offered for sale at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. It is likely that this shabti was one of those sold. It became part of the collection of the English banker Frederick George Hilton Price (1842 – 1909) and later the geologist Dr Charles Taylor Trechmann (1884 – 1964). It was then bequeathed by Trechmann to the national collection in 1965.

Mummiform shabti in bright blue faience of Nestanebashru, the daughter of Pinudjem II: Ancient Egyptian, Upper Egypt, Thebes, DB320 cache, 21st Dynasty, c.1069–945 BC. Museum reference A.1965.36.

8. Shabtis made from moulds

In January 1889, Egyptian excavators excavated the 25-foot-deep tomb of a priest of the goddess Neith - called Horudja - at a site called Hawara. The tomb had been damaged by water ingress over time, but two groups of shabtis had survived. 203 shabtis were lined up in one niche and 196 in another niche opposite. The English excavator leading the excavations, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, believed them to be some of the best examples he had seen. The shabtis were moulded in faience using 17 different moulds. In the image below you can see three from one mould and one from a second. Examples of these shabtis can be found in museum collections across the world.

Four faience shabtis, inscribed with nine lines of hieroglyphs for the Priest of Neith, Horudja, born to Shedet: Ancient Egyptian, Middle Egypt, Hawara, Late Period, 30th Dynasty, c.380-343 BC. Museum references A.1907.586, A.1907.587, A.1907.695, A.1908.283.

9. A worker of the ‘Place of Truth’

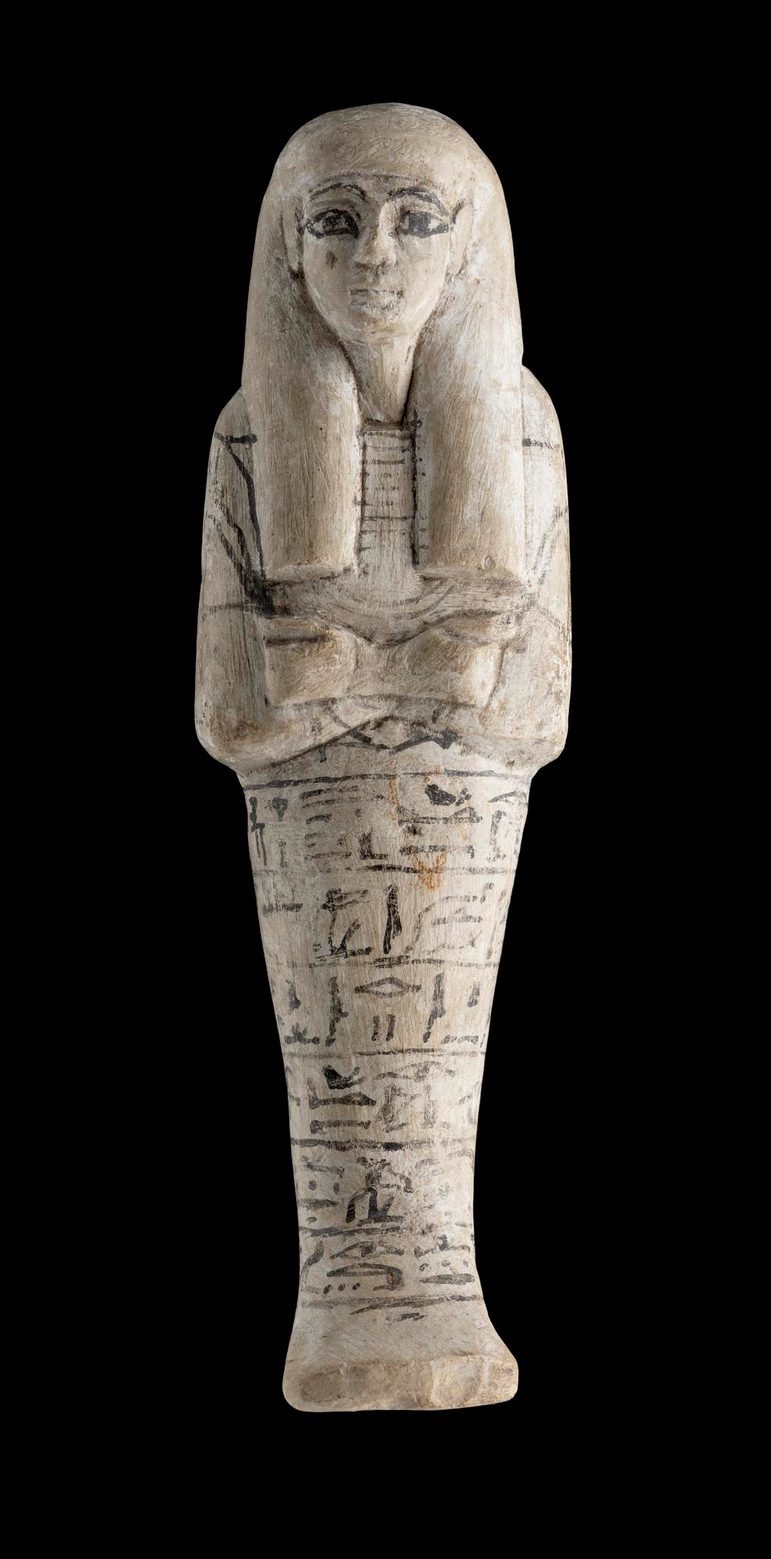

This shabti is made from limestone and is decorated with black ink. Comparing this example to other painted examples, it is possible that this one was unfinished.

The inscription tells us that the owner was a man named Pashedu and that he was a ‘worker in the Place of Truth’. This was the Egyptian name given to the Valley of the Kings by the craftsmen who were making the royal tombs. The gang of workers and their families lived over the mountain in a village that is today called Deir el-Medina. Here, next to their walled village, the workers built and decorated their own tombs.

Pashedu was the owner of an exquisitely decorated tomb which he would have worked on with his colleagues on their days off. We know from surviving documents that the workers traded things to buy or have their burial equipment made for them.

Shabti in limestone with an inscription in six lines naming Pashedu: Ancient Egyptian, Deir el-Medina, Thebes, Upper Egypt, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, c.1325 – 1275 BC. Museum reference A.1950.143.

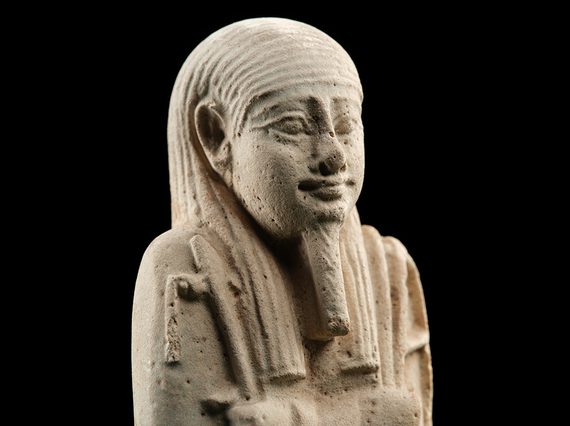

10. Oversized shabtis

Most shabtis are of a handheld size or smaller, but this large red sandstone shabti is an outlier. It comes from a select group of oversized figures that some have speculated were used like small statues. This shabti belonged to the General Kasa whose tomb was found around 1855 in the Saqqara necropolis. His tomb has since been lost but it is likely that it was near the tomb of Horemheb, a general who served under King Akhenaten, and later became king himself. The two military men are likely to have known each other.

Large format, red sandstone shabti with black wig, inscribed with four lines and one column naming, for the Overseer of the Army (General), Kasa: Ancient Egyptian, Lower Egypt, Saqqara, New Kingdom, late 18th - early 19th Dynasty, c.1325 - 1275 BC.Museum reference A.1965.35.

11. A shabti dressed for everyday

Small details on objects can reveal a lot about the ancient people who made and owned them. This shabti has a very short inscription written on it that simply provides the name and title of its owner. The man is shown wearing a linen tunic, kilt, fashionable wig and leather sandals in a style popular at the time.

The name and title reveal that this snappy dresser was likely a migrant to Egypt. They held the title Captain of Archers, common to many military men from Western Asia. Their name is written in a system used at the time to write non-Egyptian words and names so that they could be understood. It reads su-ra, indicating that the person was called something like Sel.

Shabti in green glazed faience shown in the costume of the living, with a column of inscription naming Captain of Archers, Sura (Sel): Ancient Egyptian, 19th Dynasty, c.1295-1069 BC. Museum reference A.1950.146.