Alexander Henry Rhind: The first experienced archaeologist to excavate in Egypt

News Story

Alexander Henry Rhind (1833–1863) was a groundbreaking Scottish archaeologist. His experience excavating prehistoric sites in Scotland informed his innovative work in Egypt. His early death meant that his importance has often been overlooked, but he deserves credit as the first experienced archaeologist to excavate in Egypt.

Early life

Alexander Henry Rhind was born the son of a wealthy banker in Wick, Caithness, in the north of Scotland on July 26th, 1833. It was still early days in the development of archaeology, but Rhind’s interest was sparked by his studies at the University of Edinburgh. There he was taught that it was possible to learn about life in prehistoric times from ancient objects buried in the ground.

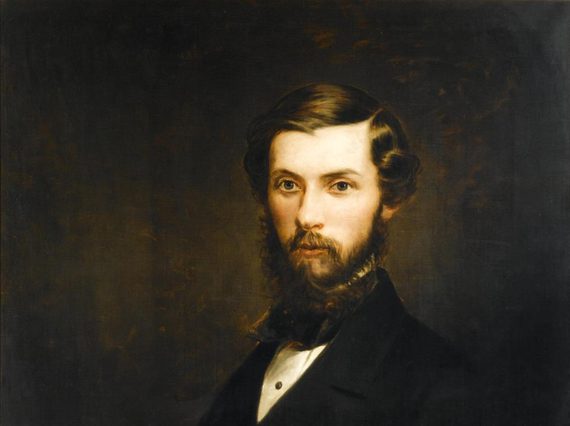

Portrait of Alexander Henry Rhind of Sibster, oil on canvas, by Alexander S. Mackay, 1874. Museum reference H.OD 7.

Excavating in Scotland

In 1853 Henry became the first person to systematically excavate a broch, a Scottish Iron Age fortified building. Kettleburn Broch in Caithness was due to be demolished by a local farmer for agricultural land, but Henry persuaded him to let him excavate there first. His team dug carefully and methodically over three months. He recorded everything that was found, including tools, combs, and animal bones, which he donated to the Museum.

At the time, museum displays were organised typologically, but Henry felt that it was important to keep the finds from Kettleburn together as an assemblage. Director Joseph Anderson would later say that the Kettleburn assemblage had given ‘a new character to the [Museum’s] collection of Scottish antiquities, and a new direction to Scottish archaeology’.

Image gallery

Pen and ink drawing of the broch at Mousa, Shetland, George Petrie, July 1865.

Hand-drawn plan by Alexander Henry Rhind of the ‘Picts’ House’ (broch) at Kettleburn, in the County of Caithness, 1853.

Travel to Egypt

Unfortunately, Henry fell ill with tuberculosis, which he suffered from for the next ten years. He travelled to Egypt, partially for his health, but also with an interest in bringing scientific process to excavations there.

Henry was shocked that no one in Egypt was excavating systematically. In the early 19th century collectors rarely recorded anything about where objects came from, which limited how well they were understood.

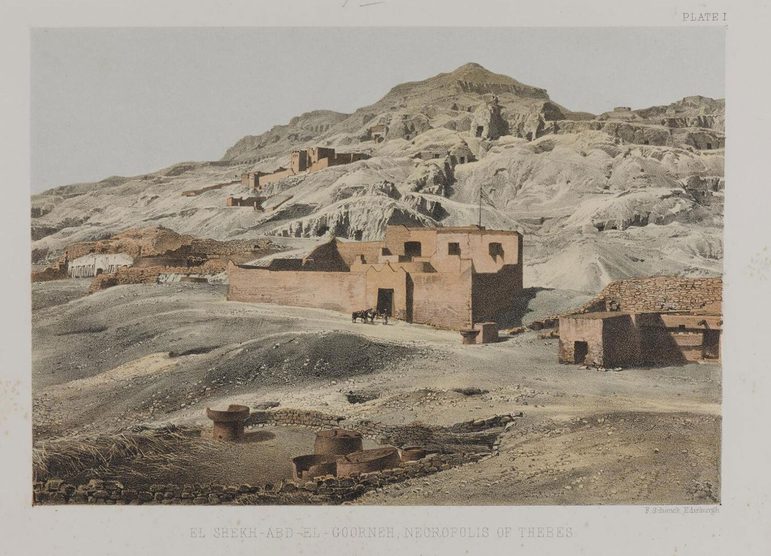

The Tombs of the Nobles and the house where Alexander Henry Rhind stayed during his excavations at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Theban West Bank (Luxor), from his book 'Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants, Ancient and Present' (1862).

Finding an intact tomb

When Henry was given permission to excavate in Egypt, he fully appreciated the great responsibility he'd been given. He set out with the objective of finding an intact tomb, so that he could record the exact locations where the objects were found. He hoped to better understand their uses and how burial practices changed over time.

Henry relied on the expertise of the villagers of Sheikh Abd el-Qurna who had been excavating tombs for many decades, in particular foreman Ahmed Abd er-Rasul. They initially found a tomb belonging to a group of princesses that had been robbed in ancient times. Little remained, but it was probably the source of an extraordinary decorative box. Next to this, they found the intact tomb that Henry had been looking for.

Detailed records

The Rhind Tomb, as it is now known, had originally been built for a Chief of Police and his wife around 1290 BC. It was then subsequently reused by other Egyptians for over a thousand years. It was finally sealed in the early Roman era with an intact family burial.

Henry recorded and drew the exact locations of each object that he found in the tomb, and brought most of them back to the National Museum in Edinburgh. He published his findings in a book entitled 'Thebes, Its Tombs and Their Tenants'. Because of his detailed records, we can still learn from the tomb today.

Image gallery

Section of the tomb plan and object illustrations from 'Thebes, Its Tombs and Their Tenants' by Alexander Henry Rhind.

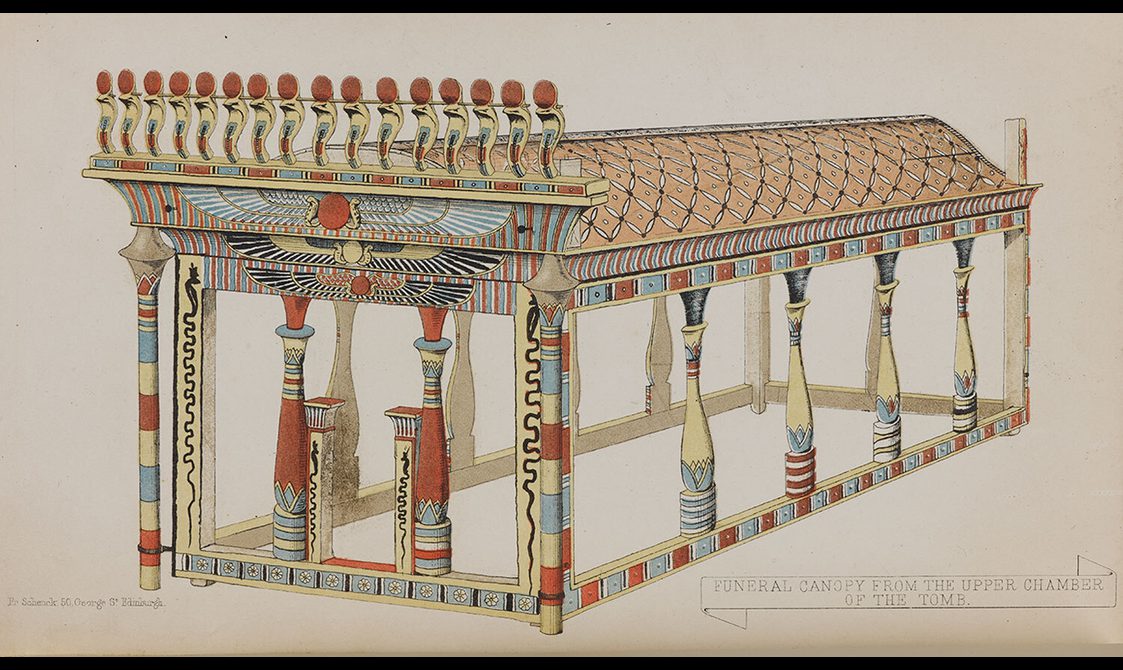

Illustration of a funerary canopy excavated by A.H. Rhind in the Rhind Tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes from his book 'Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants' (1862).

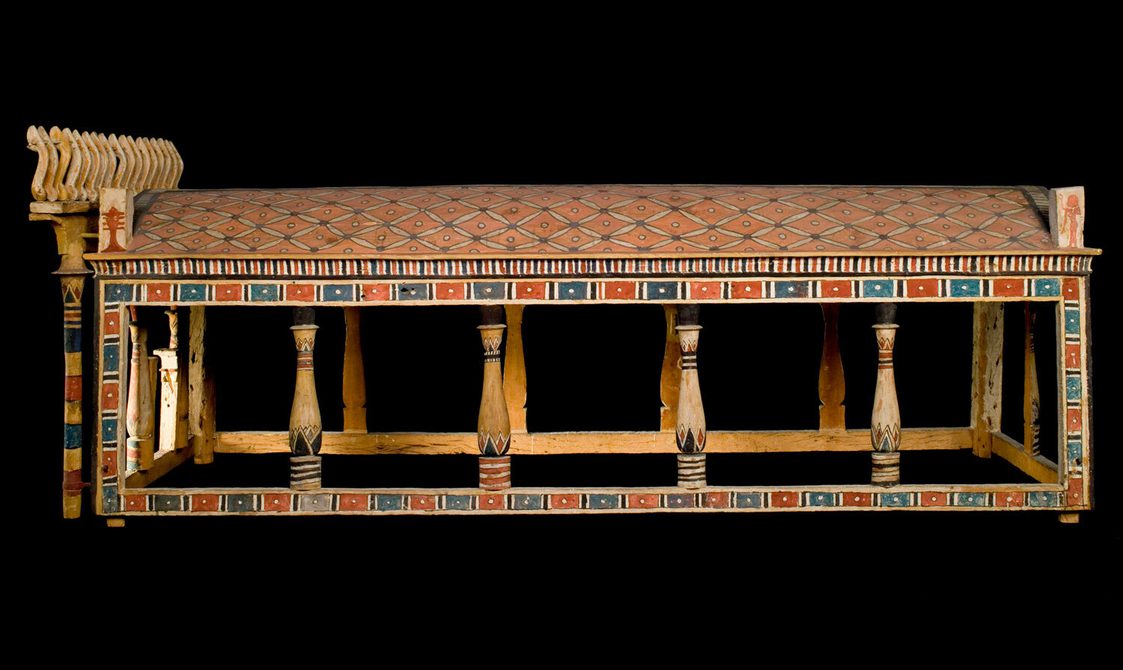

Funerary canopy of sycomore-fig wood with an arched roof and corner-posts inscribed for Montsuef, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes, c.9 BC. Museum reference A.1956.353.

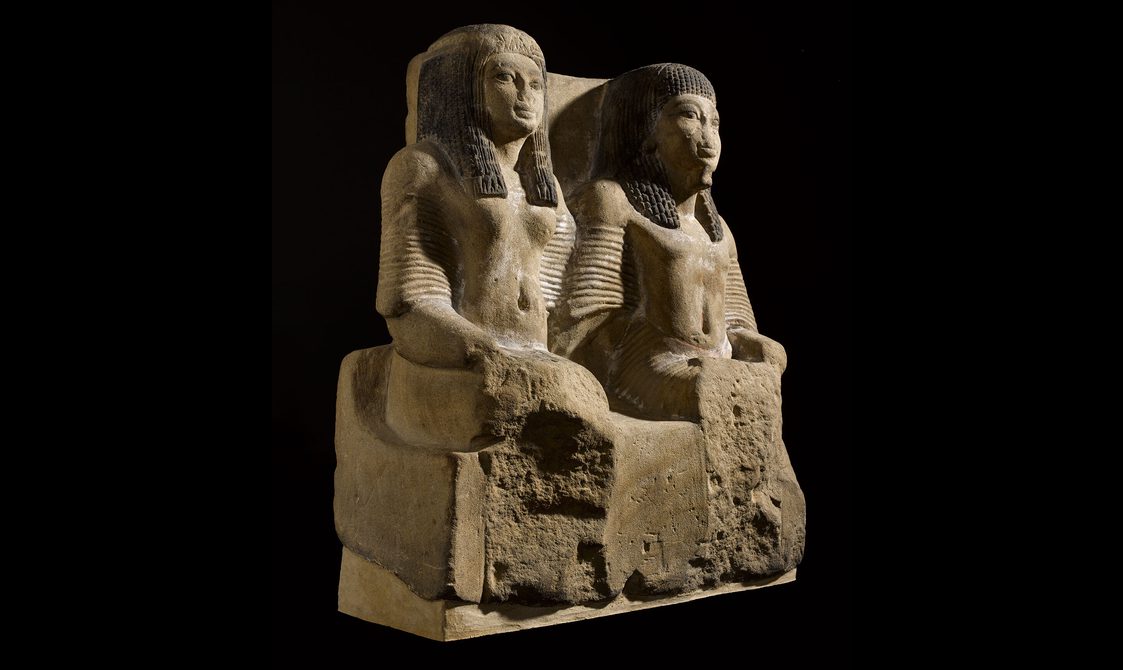

Illustration of the pair statue excavated by A.H. Rhind in the Rhind Tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes from his book 'Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants'(1862).

Illustration of the pair statue excavated by A.H. Rhind in the Rhind Tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes from his book 'Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants' (1862).

Sandstone statue of a Chief of Police and his wife, Rhind Tomb, Thebes, Egypt, c.1323–1279 BC. Museum reference A.1956.143.

Lasting legacy

As Henry grew weaker from illness, he was no longer able to excavate, but he still worked just as eagerly. He studied different Nubian dialects and investigated how the course of the Nile had changed in relation to the monuments. On his final journey home from Egypt, Henry died in his sleep aged just 29.

His promising career was cut short, and one can only wonder at the kind of impact he might have had if he had lived longer. He was beloved by his colleagues who had asked him to design the first displays at the newly formed National Museum. His work inspired Flinders Petrie who popularised scientific excavation in Egypt. Henry also left a substantial legacy to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, who hold lectures in his honour to this day. Many of the objects that he found are still in the National Museum of Scotland.

Watch this short animated film for a quick introduction to Alexander Henry Rhind.

Objects discovered in the Rhind Tomb are on display in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery on Level 5 at the National Museum of Scotland.