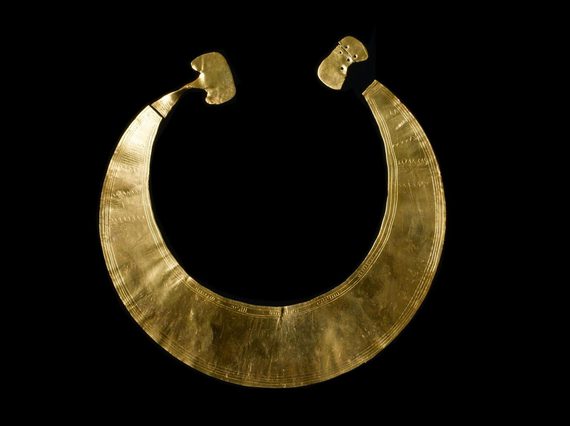

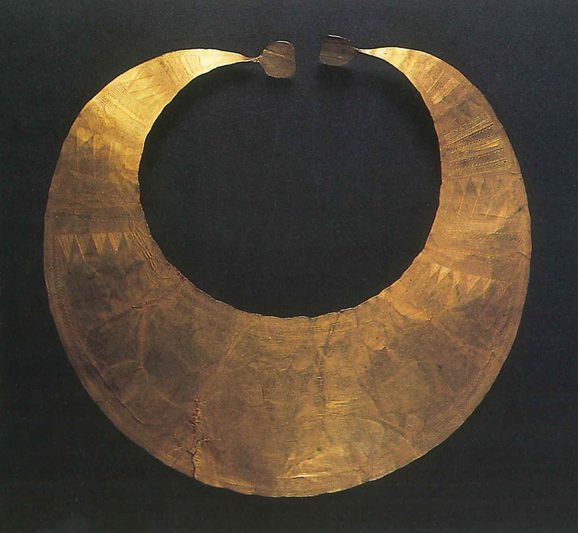

Gold lunulae from Harlyn Bay, Cornwall

Our second gold object of the week is a lunula, This large flat crescentic sheet of gold that would have been worn around the neck, like a collar.

At each end of the collar are oval or square-shaped terminals, sometimes at right angles to the rest of the object. Lunulae are iconic objects of the Early Bronze Age, dating to around 2200–1950 BC.

In 1864, two of these magnificent objects were found along with a bronze flat axehead while digging a pond at Harlyn Bay, near Padstow, in south-western England.

The making of these objects would have been a very skilled activity, requiring the hammering and shaping of a single gold ingot into the large flat collar. One of the Harlyn Bay lunulae is around 180mm in diameter, whilst the other is even larger at 210mm. These would have been carefully worked and polished to achieve a smooth finish. The gold is very thin – less than a millimetre – and the lunulae weigh 64.5g and 138 g. The heaviest lunula from Britain and Ireland is from Llanllyfni, north Wales, weighing 185g.

Both lunulae are decorated with fine lines that would have required a chisel or stylus instrument, perhaps made of bone, bronze or wood. Some of the decoration may have been impressed into the gold, due to the soft nature of the material. From the decoration we can learn a lot about the craftsperson who performed the task by looking at the style and the tool marks left on the objects.

Image gallery

One of the Harlyn Bay lunulae is identical to another that was recovered from Kerivoa in Brittany, France. But how did two identical objects end up on opposite sides of the English Channel? It has been suggested that these two lunulae may have been made by the same craftsperson who either travelled or traded across north-western France and south-western England. We often struggle to see indicators of specific craftspeople in the past, but these two objects offer us a rare glimpse.

Around 100 lunulae are currently known across north-western Europe, with the majority – over 80 – having been found in Ireland. Indeed, this seems to be where the first lunulae were made, and where many of the most highly decorated and most skilfully-made lunulae are found. These are typically referred to as ‘Classical’ lunulae and almost all have been found in Ireland, apart from three in Cornwall, that is the one from Harlyn Bay and two others from St Juliot and Gwithian. The majority of the lunulae found outside Ireland are a bit thicker and display less decoration. These are referred to as ‘Provincial’ lunulae. The two from Harlyn Bay represent Classical and Provincial styles, indicating links between south-western England and Ireland. The Classical form is larger but lighter in weight, whilst the Provincial form is smaller, heavier and thicker.

Ireland has much native gold, but recent research by Dr Chris Standish on the origins of the gold used to make Early Bronze Age objects found in Ireland and Scotland has concluded that Cornwall was the source of the gold. The metal was probably extracted from stream deposits and transported from south-western England to Ireland, where it was then made into objects such as lunulae. The connection between Cornwall (and Devon) and Ireland is very important, since it was tin from streams there that was exported to south-west Ireland from around 2200 BC to be alloyed with copper from Ross Island copper mine in County Kerry to make bronze. Gold can be found in the same streams in Cornwall and Devon as tin, so it seems likely that gold (probably in ingot form) was exported to Ireland along with tin. For a finished lunula (or lunulae) to travel to Cornwall therefore looks like a case of ‘Sending coals to Newcastle’!

The Harlyn Bay find is important not just in highlighting the Early Bronze Age connections between south-west England and Ireland, but also in confirming the date of lunulae. The axehead found with the lunulae is made of bronze and is of a type known to have been made between around 2200 BC and 2000 BC. This is consistent with the style of the decoration on lunulae, which matches that on the Beaker pottery that was in use at the time… but that’s another story, to which we shall return later.

As you can see, these objects have lots to tell us about how Early Bronze Age Europe was connected, with the trade and exchange of materials and ideas forming an active part of prehistoric society.

The Harlyn Bay lunulae and flat axehead are currently on display at Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro. We are grateful to Andy Jones, Anna Tyacke and Sophie Meyer for information and images of the lunulae.

Dr Matthew Knight, Senior Curator, Early Prehistory on m.knight@nms.ac.uk