Abernethy Pearl: Scotland's largest freshwater pearl

News Story

In 1967, Bill Abernethy was pearl fishing near the River Tay when he came across his rarest and greatest discovery. At a weight of 43.6 grains, the Abernethy Pearl is the largest freshwater pearl found in Scotland in modern history.

A single fresh water pearl collected near the River Tay in 1967 by Bill Abernethy. Museum reference G.2025.11.1.

The Abernethy Pearl is often spoken of with quiet reverence. It is the largest known pearl since the rarely seen Kellie Pearl, discovered in 1621. Born of Scotland’s wild rivers, it is a jewel of extraordinary size – perfectly round and softly glimmering with a pink sheen. Its formation took decades, a process that reflects a patience far beyond human measure.

But the pearl is more than a jewel to be weighed in grains or measured in millimetres. It is more than a remarkable testament to the interconnectedness of life and minerals. It tells a story of times long past: of mussels labouring unseen beneath the riverbed, crafting their treasure in an environment that is now so fragile it is under threat.

Imperfect pearls from the Rivers Tay and Earn. Museum reference Z.1913.1.18.

A suprisingly large gem

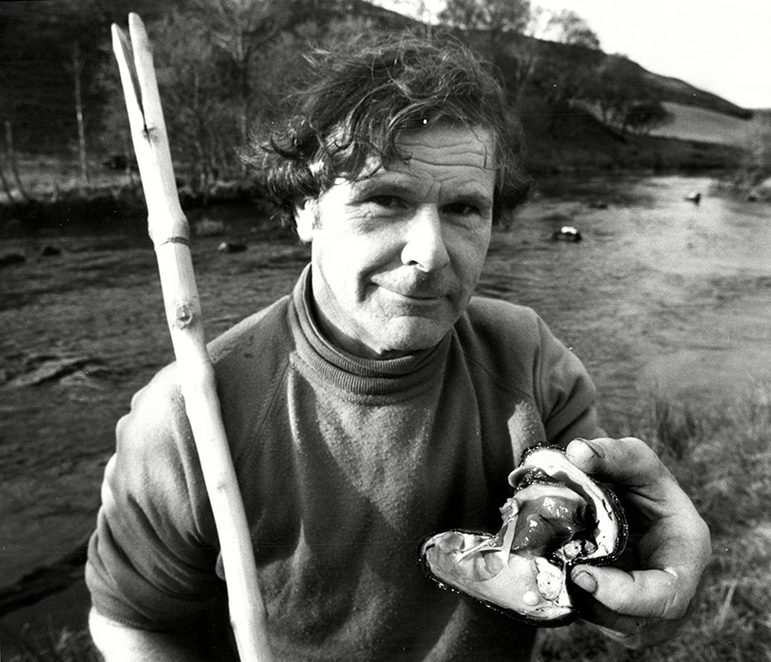

The Abernethy Pearl was discovered in 1967 by Bill Abernethy, the last of Scotland’s professional pearl fishers. Bill had learned the craft from his father, a tradition shaped by the flow of rivers and the chance gifts hidden within their mussels. A lifetime of observing, walking and wading left him with a deep respect and concern for the enduring health of Scotland’s wild environment.

When Bill prised open the moderately-sized shell that day, he was sure he would find a pearl. Although only one in five thousand mussels contain a pearl, Bill could spot the subtly deformed shell shape that indicated there might be treasure contained within. Yet even he – after decades of experience – was astonished at the gem’s size and beauty.

Bill Abernethy with a mussel shell and pearl at Glen Esk, Brechin in Dundee and Angus.

What makes a pearl?

Pearls are small miracles of biology and geology working together. They begin with the smallest seed in the form of an intrusion. A tiny irritant manages to slip through the mussel’s shells and enter its home. In response, the creature wraps a substance called nacre (also known as mother-of-pearl) around the intrusion to contain it. Nacre is made of many thin and overlapping crystals of the mineral aragonite held in place with thin strands of protein.

Delicate, colourless crystals of Aragonite with calcite, galena and sphalerite, from the New Glencrieff Mine at Wanlockhead, Dumfriesshire, Scotland. Museum reference G.1951.8.13.

Aragonite is a crystalline form of calcium carbonate. It's composed of calcium, carbon, and oxygen. Though chemically identical to the more common mineral calcite, its structure is different. Aragonite in nacre forms thin, clear, pseudo-hexagonal plate-like crystals.

Layer upon layer, over years, the mussel lays down these microscopic sheets of protein and crystals. When eventually the pearl is exposed to the light, the countless thin, overlapping crystals split, reflect and refract light, scattering it and creating the shifting shimmer we call pearlescence. Most mussels never make such treasures – many hold nothing at all. Many at best create dull, misshapen lumps, known as blister pearls, welded to the wall of its shell. A perfect sphere with such a sumptuous lustre is the rarest find.

The Abernethy pearl resting in its open mussel shell. Museum references G.2025.11.1. and G.2025.11.2.1.

Sought-after Scottish treasures

In Scotland, precious pearls are found in native species of freshwater mussel. They once thrived in clean, cool, swift rivers across the land. They are one of the longest living organisms – living for a century or more, filtering the waters, each one a quiet witness to changing landscapes. Yet the beauty that is held within their shells for so long is also held at their peril.

Since at least the Roman times, people have pursued pearls. Queen Victoria took a special delight in necklaces and brooches adorned with Scottish gems, and countless unnamed fishers have plunged into cold waters with hope in their hands.

Today, however, the fate of pearls has become entwined with our own. Salmon and trout are needed for the young mussel larvae to survive. With declining fish numbers, disturbed rivers, a warming climate and overfishing, the number of mussels has catastrophically diminished and we can no longer harvest them.

Brooch made from native gold sourced in Sutherland, set with a central cairngorm stone and surrounded by four Scottish freshwater pearls, by Glasgow jewellers Muirhead & Son, c. 1868-1873. Museum reference:

X.2018.17

The ban on pearl fishing in 1998 was as much a lament as a law. It was a recognition that something precious was slipping away.

Today, the pearl reminds us that beauty resides not in crowns or museums, but also in what nature creates from minerals – slowly and quietly – in an environment that we must cherish if it is to endure.

The Abernethy pearl. Museum references G.2025.11.1. and G.2025.11.2.1.

The Abernethy Pearl is now on display in the Restless Earth gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

Written by

Dr Rachel Walcott

Principal Curator of Earth Systems