Digging for context: Celtic art and fieldwork at Torrs

News Story

Dr Fraser Hunter explains how digging around in the mud and wading through peat is helping uncover the origins of magnificent and enigmatic objects such as the Torrs pony cap.

So many of the finest items in our collection come from bogs, lochs and rivers – this was no accident, or repeated carelessness. They were placed there as offerings – perhaps sacrifices to some unknown god, or the remains of rituals at moments of crisis or times of triumph. The Castle Douglas area is rich in such finds.

We wanted to examine the find-spot of the amazing Torrs pony cap, which was a star piece in our Celts exhibition. Why was it there? What was the watery landscape like at the time, before it was all drained during the improvements of the 18th and 19th century? And where did the likely owners live?

The Torrs pony cap. Museum reference X.FA 72.

Group activity

So much for theory, what could we do? Well, there’s no problem that doesn’t improve after a few days of shifting mud in the field.

Colleagues from the universities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Stirling saw a link to their own research, and came along to lend a hand, and added to the discussion, debate and disagreement which is the lifeblood of archaeology.

Equipment for the dig.

Analysing an ancient landscape

The findspot of this Iron Age masterpiece lies close to Castle Douglas in Galloway, but the exact location isn’t clear. It was found in 1812, when recording was a wee bit less precise than today! We knew it was discovered in peat, probably during drainage works, in an area which used to be a loch – but there are several candidates as this was once a very wet spot.

We aimed to establish how big the lochs and mosses in this area were during the Iron Age, some 2200 years ago, and see if any peat survived of this date which we could slice, dice and dissolve to extract pollen and tease out a history of the ancient landscape.

We wanted to see if we could pin down where the pony cap came from and find out what was happening in the area at the time, during the third century BC. So we looked at a nearby Iron Age very battered hillfort and explored the surrounding landscape by various scientific techniques.

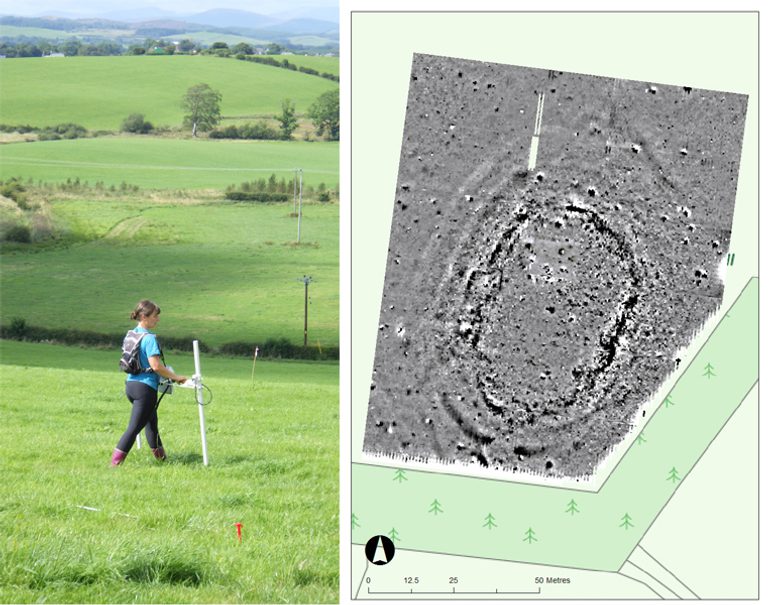

We used geophysics, the magic which lets you see beneath the soil, in the high patches of land between the bogs and mosses, looking for possible settlements. We used a technique called magnetometry, measuring variations in the earth’s magnetic signal caused by things such as cooking hearths and rubbish dumps.

Left image: Geophysics in action – Tessa Poller surveying the hillfort. Right image: Results of the magnetometer survey of the hillfort.

A quiet hillfort

The hillfort survives as subtle mounds and hollows marking the plough-worn ramparts and ditches, though it takes a trained eye to see them. Thanks to our colleague Tessa Poller from Glasgow University, we were able to get a preview of what lay under the turf of the hillfort.

The results were fascinating. The hillfort jumps out at you, with two curving oval lines of the ditches and a messy black and white circuit marking the rampart. This was intriguing, as it suggested there was a lot of magnetically-rich stone in it.

You can see a clear entrance at one end, and subtle traces of a later rectangular building reusing the rampart, but what’s really interesting is how quiet the interior is. There’s no hint of houses or hearths.

This whetted our appetite. We set about digging a big trench over the rampart system. There were two whopping great ditches, which tested our fitness as we dug out the thick, heavy clay layers in the base, and remains of a big rampart.

Digging across the ramparts and ditches.

This had a long history with at least three phases. The first rampart was a large dump of earth and clay with stone revetments. It was refurbished at least once, and then rebuilt in a different style.

This last phase had two concentric timber palisades held fast in stone-lined slots (which formed the messy black and white line on the geophysics). The palisades would have been linked together into a hefty timber-framed structure known as a box rampart, which must have used an enormous amount of wood.

Digging through the backfill of the inner ditch.

Quiet trenches

The interior was more of a challenge. We dug two big trenches, but found almost nothing – except a 19th-century trig point from the early Ordnance Survey mapping of the area!

Unexpected rock art! An early trig point.

We tried other techniques, working with local metal-detectorists to look for clues. They slaved long hours in unyielding terrain, producing a crop of horseshoes and tractor parts, but nothing of any great antiquity.

Hunting for clues with a metal-detector. The red flag marks precisely where a find comes from.

Extra helpers

We also had local schools out to learn about their own history, to see what archaeologists do – and to lend us a hand, (There’s a thin line between enthusiastic assistance and child labour, but I think we stayed on the right side of it …)

School children from Castle Douglas Primary School helping us by sieving the topsoil, oblivious to the weather.

The results of this were interesting. The kids sieved the mixed-up ploughsoil which we’d taken off with a JCB. They found lots of modern material and some bits of flint and quartz from earlier prehistory, but nothing to suggest an Iron Age settlement – not even charcoal and burnt stone, which is the standard debris from a prehistoric site.

Along with the lack of pits and postholes, it suggests this hillfort wasn’t a permanent settlement. More likely it was a central place for a community’s ceremonies and rituals, a place of safety and gatherings.

But the kids did reveal some lovely finds. The highlight was a broken flint knife, its edges beautifully shaped by careful chipping. This dates back about 4,000 years, to the Early Bronze Age.

A lovely Early Bronze Age flint tool.

Relying on the landscape

So, we have an Iron Age fort which was used but not lived in. We didn’t yet know its precise date – we’d no diagnostic finds, so we would need to rely on fragments of charcoal and charred seeds to get radiocarbon dates, if there is actually any charcoal in our samples!

What about the wider landscape? Survey of the area by Michael Stratigos (Aberdeen University) and Richard Tipping (formerly of Stirling University) showed that the hillfort stood on what was virtually an island in prehistory, with bogs all around.

Richard Tipping examining a core through peat and loch sediments.

The drainage schemes of the 18th and 19th centuries have totally changed the landscape here. But we could reconstruct it thanks to cores drilled into these former lochs and bogs.

We showed that there are rich, well-preserved peat deposits which survived the 19th-century drainage, and these contain vital clues to the environment at the time.

Rainbow over Torrs Moss – a clue as to where the pony cap came from…?

We could also be quite confident that the cap was found in Torrs Loch, as this fitted all the clues from early accounts. It was buried in the marshy fen edges of the loch, probably as an offering. But any other offerings remain hidden – the peat has only given up a few of its secrets so far…