Freddy the Robot: A 1970s glimpse into the future

News Story

Developed in the 1970s at the University of Edinburgh, Freddy the Robot was the world’s first 'thinking robot' to combine a seeing eye and a feeling hand.

It was part of an important era in robotic development, and was amongst the first to integrate intelligent systems capable of calculating its own movements to complete a task.

The origin of robots

Mentioned in ancient mythologies, legends, and many works of fiction, the concept of artificial humans has captured the imagination, and inspired attempts to create real thinking machines throughout history.

Automata

Automata are machines that work by themselves, usually with a clockwork mechanism. Music boxes are a very simple example. As far back as Ancient Greece, human-like automata were devised and used for religious ceremonies.

From the 18th century, automata became more complex — able to write, draw, perform music, and present elaborate spectacles.

'Robot'

The term 'robot' was first used in a 1920 Czech play, Karel Čapek Rossum’s Universal Robots (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti), about a factory which made artificial workers. The word 'robota' means 'hard work' or 'forced labour' in Czech.

Industrial robots

Experiments with industrial robots began in America in the 1930s. By the 1940s, research and debate had turned to the creation—and consequences—of thinking machines. In 1942, Isaac Asimov introduced the Three Laws of Robotics in a science fiction story. In 1950, Alan Turing devised The Turing Test to determine if a machine could exhibit intelligent behaviour. These ideas had a profound effect on other science fiction writers, as well as on future research and development in robotics.

Two such inventors were Americans: George Devol and Joseph Engelberger. Their aim was to create a working robot which could carry out tasks which were unpleasant for people, such as moving hot pieces of metal and welding. UNIMATE, designed in 1956, was the world’s first programmable industrial robot and began work at a car factory in 1961.

The birth of intelligent robotics

The 1970s were a vital and pivotal period in the advancement of robotic technology. Transformative experiments with autonomy, complex object assembly, and space exploration were the building blocks of robotics and artificial intelligence as we understand them today.

Shakey the robot

Shakey was designed and built between 1966 and 1972 at the Stanford Research Institute in the USA. It was the first mobile robot to use artificial intelligence to move without direct human instructions. Shakey used a TV camera and ‘bump sensors’ to avoid obstacles, and moved at the giddying pace of two metres per hour.

The 'Freddys'

Naming machines after people was a common practice in robotics research to help teams connect with their creations and make discussions easier. While there’s no official record of why “Freddy” was chosen specifically, the name helped bring personality to this early example of intelligent robotics. In 2002, Donald Michie who had led the research team, said that the name derived from Friendly Robot for Education, Discussion and Entertainment, the Retrieval of Information and the Collation of Knowledge.

There were three ‘Freddys’: Freddy I was made between 1969 and 1971, and then Freddy 1.5 in 1971. The robot in our collection, Freddy II, was developed from Freddy 1.5 between 1973 and 1976. All three were built by researchers at the Department of Artificial Intelligence (AI), University of Edinburgh. They were designed to be 'thinking robots'.

Freddy I was a more basic experimental prototype, comprising a rotating platform, a video camera for recognising objects, and bump sensors. It sat on a circular platform. The robot pushed the platform around using the steel balls that the platform rested on. It could detect obstacles on the platform and had a mounted camera. It was capable of recognising irregular objects.

Freddy 1.5 had a complete hand-eye system, and a much larger and square platform which moved in two directions. Instead of moving along the platform it was suspended from a large frame above, with a camera looking down. It had a couple of vertical arms with flat plates, designed to grip objects like rudimentary hands. The system was controlled by one computer.

Our Freddy

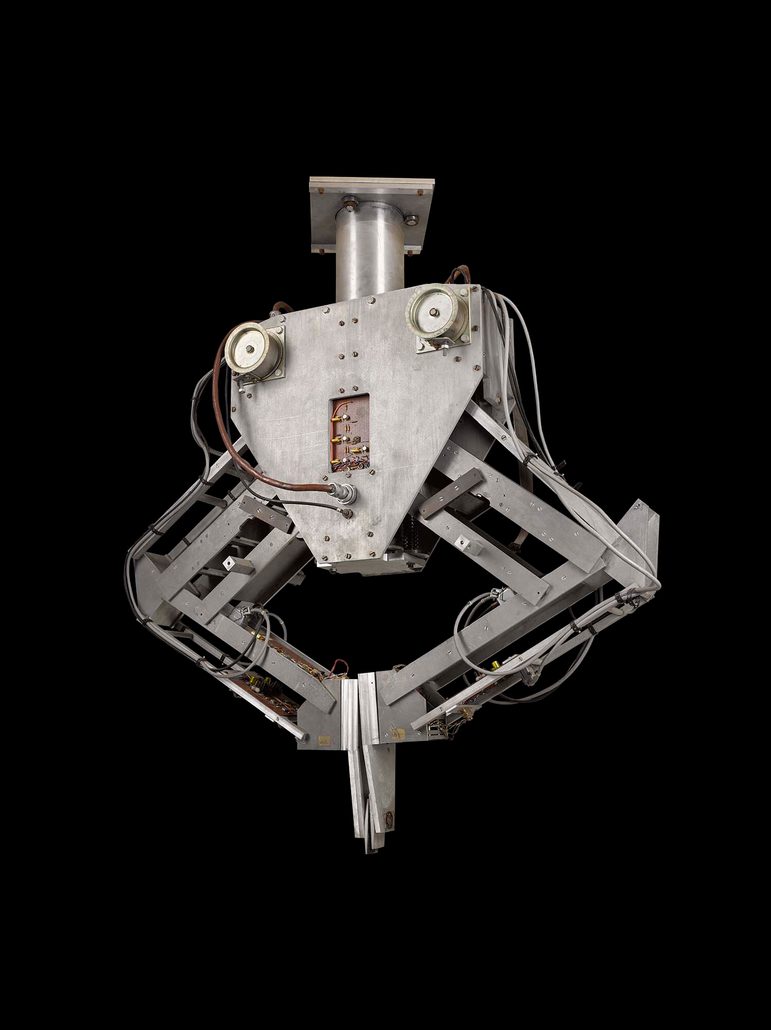

Freddy II was an enhancement of Freddy 1.5. It offered greater versatility of movement, with tilting ‘hands’, the ability to grip objects horizontally, two camera eyes, and bump sensors.

This Freddy was run by two computers, programmed with the moves that the robot might need to make, and with scenarios it might encounter. These computers were linked to the two camera ‘eyes’ — one looking straight down and one at an angle.

Freddy II's grip had better pressure sensitivity. The innovative platform beneath the robot’s hand moved side to side, and back and forth. It also had better visual recognition.

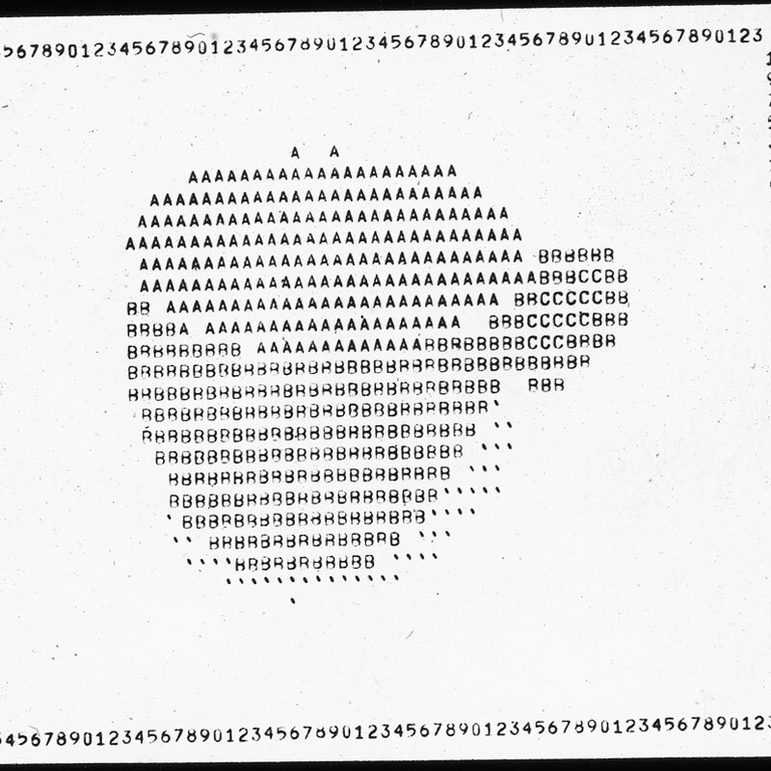

It was designed to perform a few tasks in a way similar to a five-year-old child. The development team found they had underestimated just how intelligent a child was. Freddy could be trained to carry out new tasks, such as putting rings on a peg or assembling simple model toys.

One task they taught Freddy was to put scattered pieces into a box — but it did the job too well, and tried to tidy the box away too.

Watch a short film showing Freddy assembling a toy car and boat from a pile of parts. This film has been sped up; the task took about 16 hours in total.

Freddy was decommissioned in 1980 and is now on display at the National Museum of Scotland.

Freddy's legacy

The development of Freddy directly led to more advanced robot programming languages, which replaced the tedium of lengthy single-input instructions like ‘move here, do this, stop’ with a focus on the robot and its position in relation to surrounding objects.

In the mid 1970s, there was much debate and pessimism regarding the viability of robotics in artificial intelligence. Both Shaky and Freddy were cited in a Science Research Council report and TV programme, which led to a lack of investment and 'AI winter' in Britain in the late 1970s. However, since the 2000s, there has been an explosion in robotics and what was known as ‘machine learning’.

Freddy II was a pioneering step in robot autonomy and adaptability. Its ability to sense, make decisions, and perform different tasks helped lay the groundwork for the versatile robots we see today—robots that operate in hazardous environments, explore space and the deep ocean, assist in surgery, and monitor and dispense products around the world.