Pocket watch from the shipwrecked Swan: a clockwork revelation

News Story

Salvaged from a shipwreck, this pocket watch has lain hidden under water for over 300 years. Now, a high-tech process has uncovered the amazing hidden secrets of this rusty artefact.

The sinking Swan

In 1653, during the turbulent years following the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell—by then Lord General of the New Model Army and de facto leader of the English Commonwealth—turned his attention to unrest in Scotland. Cromwell's forces had crushed the Scottish army by 1651, but Royalist resistance remained, especially in the Highlands and along the western seabord.

To suppress a Royalist rising in autumn 1653, Cromwell sent a flotilla of six ships to the west coast. Among this force was a modestly-sized warship called the Swan.

During the operation, a furious storm blew up. Three of the ships were dismasted and left helpless and adrift, whilst the other three, including the Swan, were smashed to pieces against the rocky shore - though most of the men were ashore at the time.

The wreck of the Swan lay at the bottom of the Sound of Mull until it was rediscovered in 1979 by a naval diving instructor, John Dadd. Subsequently, a multi-year programme of underwater archaeology, led by a team at the University of Saint Andrews, discovered a wealth of important artefacts and stabilised the wreckage site, which was at risk from active erosion of the seabed.

The Finds

The site has provided a remarkable snapshot of life on board a small warship in the tumultuous mid-17th century.

Among the objects recovered from the Swan were a large group of silver coins, carved decorative woodwork, a brass lock-plate from a Scottish snaphaunce pistol, a cast-iron gun, and prized possessions such as an ornate sword hilt decorated with gold and silver wire, and a pocket watch.

The pocket watch was particularly significant, as very few watches from this period have been recovered from archaeological sites, which means we know they have not been altered by later owners. Of note are a 17th century pocked watch from the Cheapside Hoard, London, and an 18th century silver pocket watch found on the wreck of HMS Pandora (wrecked in 1791) in 1983.

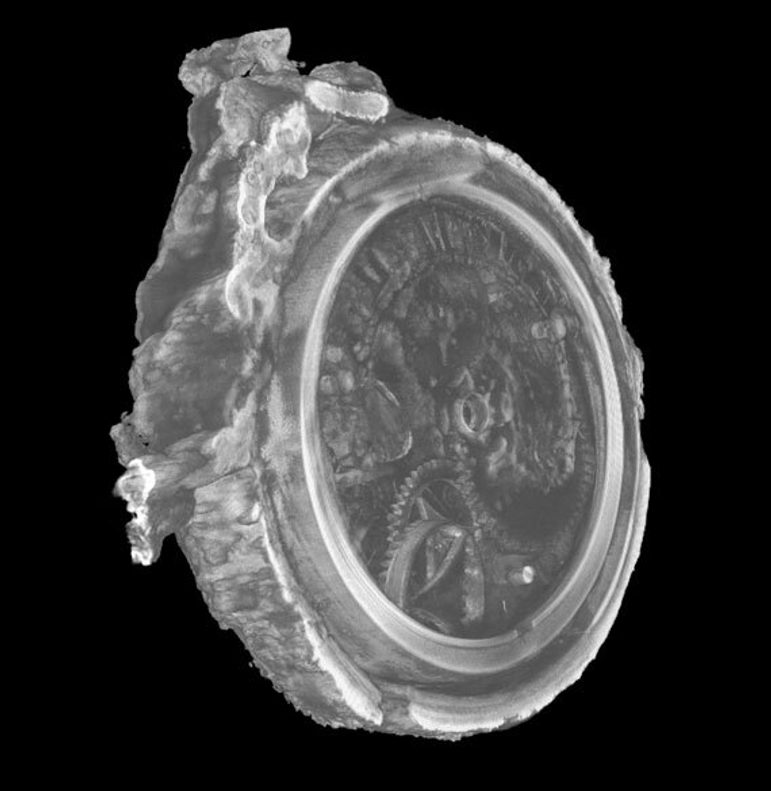

The pocket watch discovered amongst the wreckage of the Swan.

What lay beneath the corrosion

From the outside, the watch appears corroded beyond recognition: a rusty mass encrusted with barnacles. All that can be seen of the watch through breaks in the outer case is a black mass of silver corrosion. X-ray radiography undertaken in 1994 revealed a welcome surprise; some parts of the watch’s mechanism had been preserved.

Unfortunately, further traditional conservation work was limited and could do little more without damaging the watch. However, in 2005, innovative research using X-ray computed tomography (CT) was applied to an Ancient Greek astronomical calculator, The Antikythera Mechanism, with promising results.

It was decided by the conservation team at the National Museums Scotland to apply this technique to the watch.

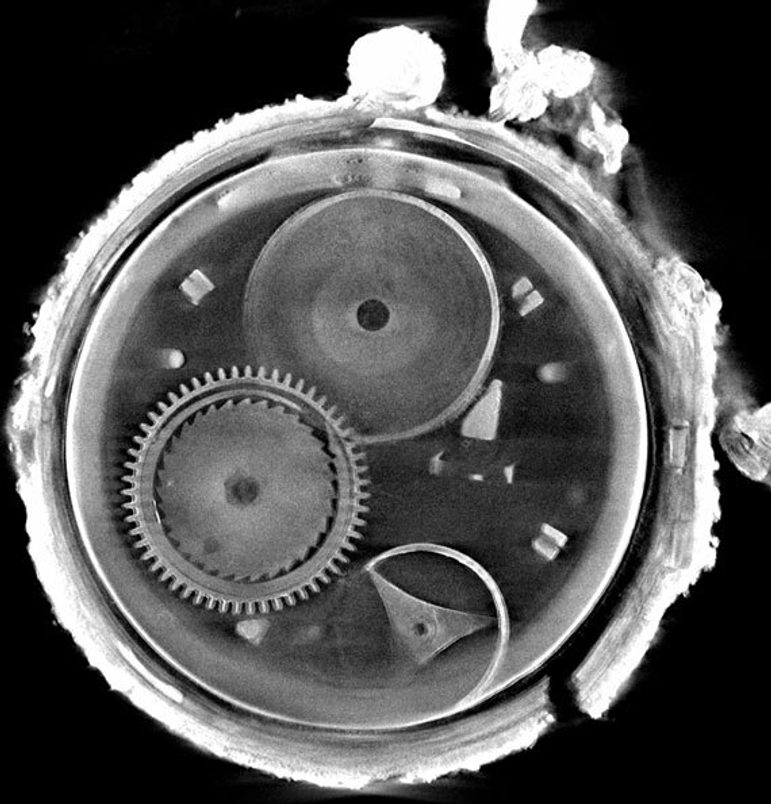

A 2D slice of the Swan pocket watch through the 3D-CT volume showing the sawtooth shaped fusee click teeth.

In 2007 the watch was scanned at X-Tek System Ltd (today part of Nikon Metrology), using high-precision micro-focus X-ray computed-tomography system (3D-CT), a technology which builds two-dimensional cross-section images into a high resolution 3D reconstruction.

"Three dimensional and two dimensional CT will allow us to move around the virtual space, to strip away components, and slice it in any arbitrary direction to see interior details. So technically it should be possible to view with clarity the tiniest part of the mechanism and maybe also some engravings."

Lore Troalen, Analytical Scientist, Conservation and Analytical Research Department, National Museums Scotland.

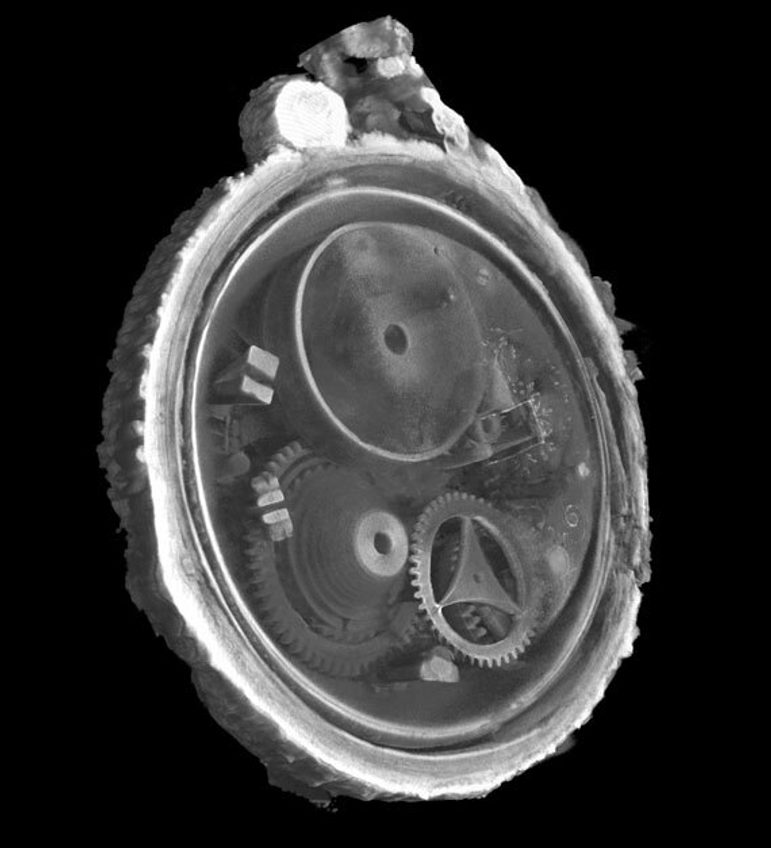

A 2D slice through the 3D-CT volume showing the watch front.

Astonishing results

The results were amazing and exceeded everyone's expectations. Not only was the watch’s face clearly visible, engraved with Roman numerals and an English rose at the centre, but the scans also showed the workings of the watch in fine details.

By examining the scans, Darren Cox, conservator of clocks and watches, was able to conclude that the watch was typical of the period. It has a single-train movement, meaning the mechanism keeps time but does not strike or chime.

A 2D slice through the 3D-CT volume showing the inner workings of the watch.

The steel components (spindles, pallets, wheels) had corroded and were missing from the X-ray, whilst the brass fittings appeared in good condition. Good enough that the teeth could be counted on the cogs.

The inner case was a simple construction and of a plain design. whilst the outer case had unfortunately eroded, making it impossible to confirm the watch's style.

"... decoration on watches during this period was moving from the inner case to the outer case, and many inner cases on watches (not only 'puritan' ones) made in the second quarter of the 17th century were plain. "

Darren Cox, conservator of clocks and watches, National Museums Scotland.

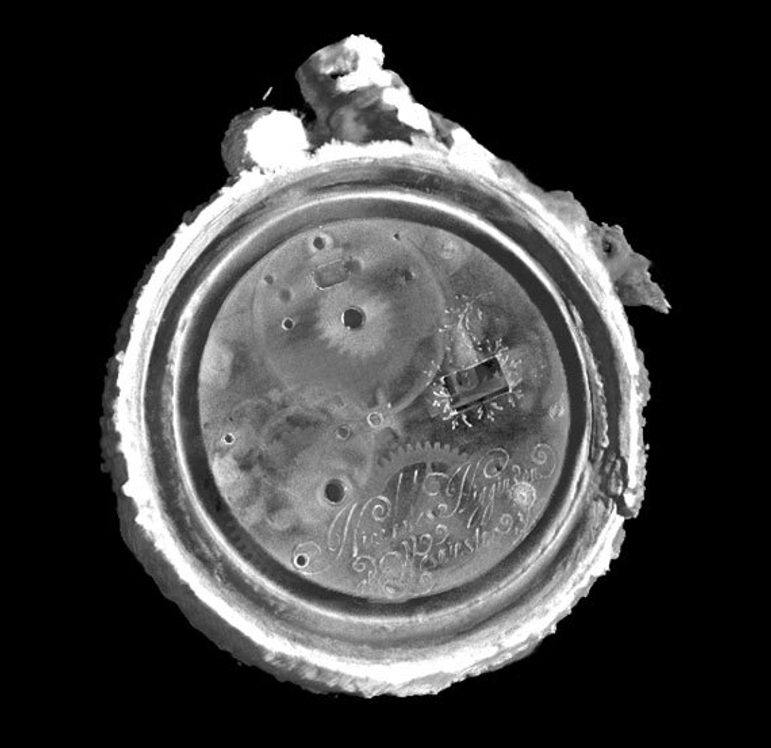

A 2D slice through the 3D-CT volume showing the back of the watch.

Nicholas Higginson, clockmaker

Perhaps the most exciting discovery was the name of the maker engraved on the back plate, 'Niccholas Higginson, Westminster'.

Nicholas Higginson came from a renowned clockmaking family. He and his brother John were both apprenticed to The Blacksmiths Company, later becoming prolific and independent clock or watchmakers.

Research in Clockmakers' directories revealed that Nicholas Higginson was registered in the Clockmakers’ Company from 1646 until 1656, and in workshops in Chancery Lane and Westminster. This authenticates the date of the watch, prior to the sinking of the Swan.

A 2D slice through the 3D-CT volume showing a floral engraving and the engraved signature: Niccholas Higginson of Westminster.

Revealing the mechanism

This film shows an x-ray of the watch, in which its components can be clearly seen.

Rare and precious

A watch of this calibre would have belonged to someone of considerable wealth or status—most likely the Swan's captain, Edward Tarleton.

This is the only watch signed Niccholas Higginson known to survive.