Roman-era personalised funerary papyri

News Story

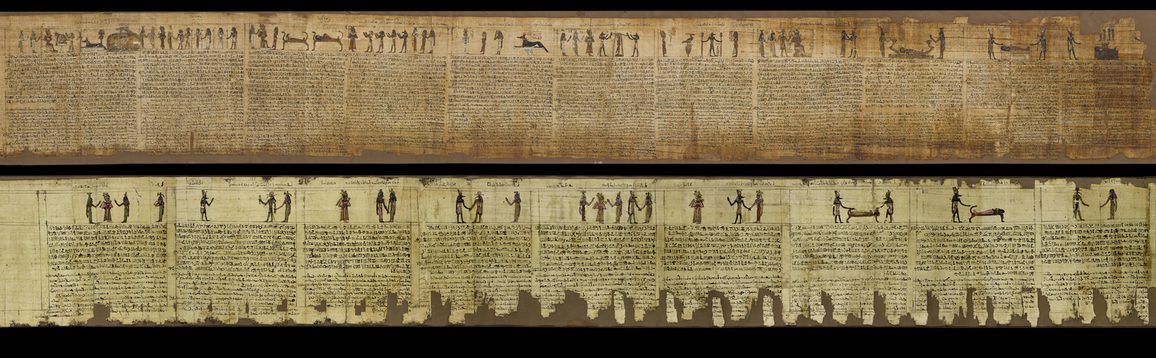

Two detailed funerary papyri date to exactly 9BC, shortly after the reign of Cleopatra, the last pharaoh of Egypt, and the Roman conquest of Egypt. These papyri tell the unique stories of a couple from ancient Egypt. We delve into these papyri to understand the life and death of high official Montsuef and his wife Tanuat.

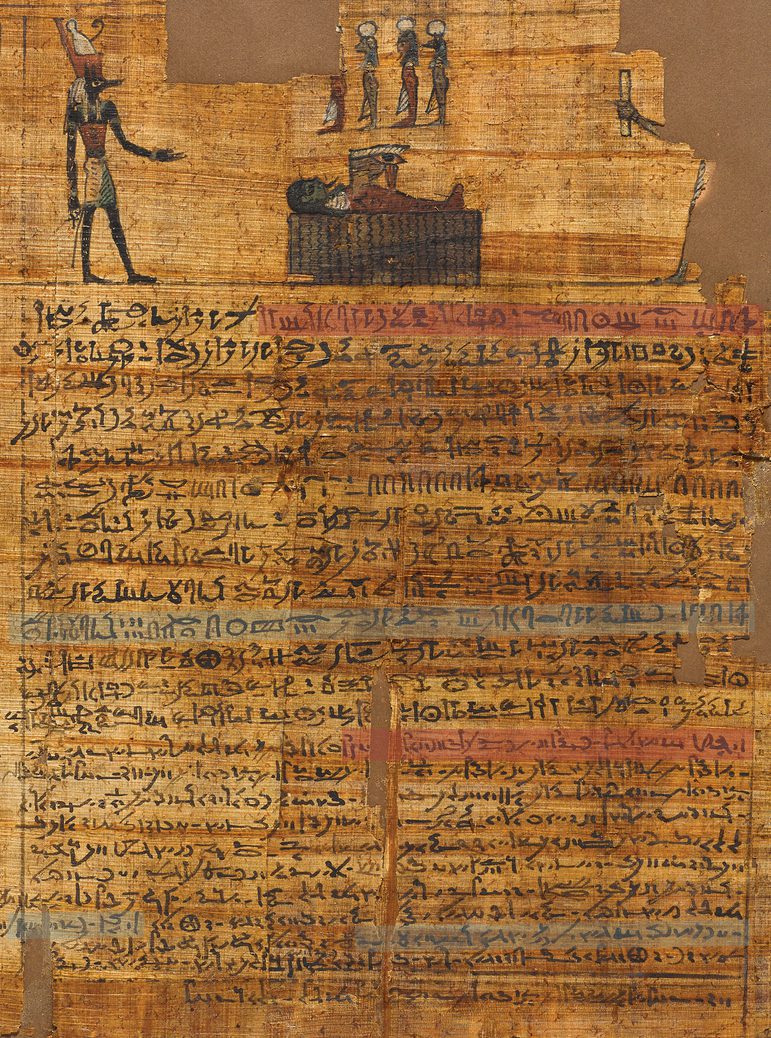

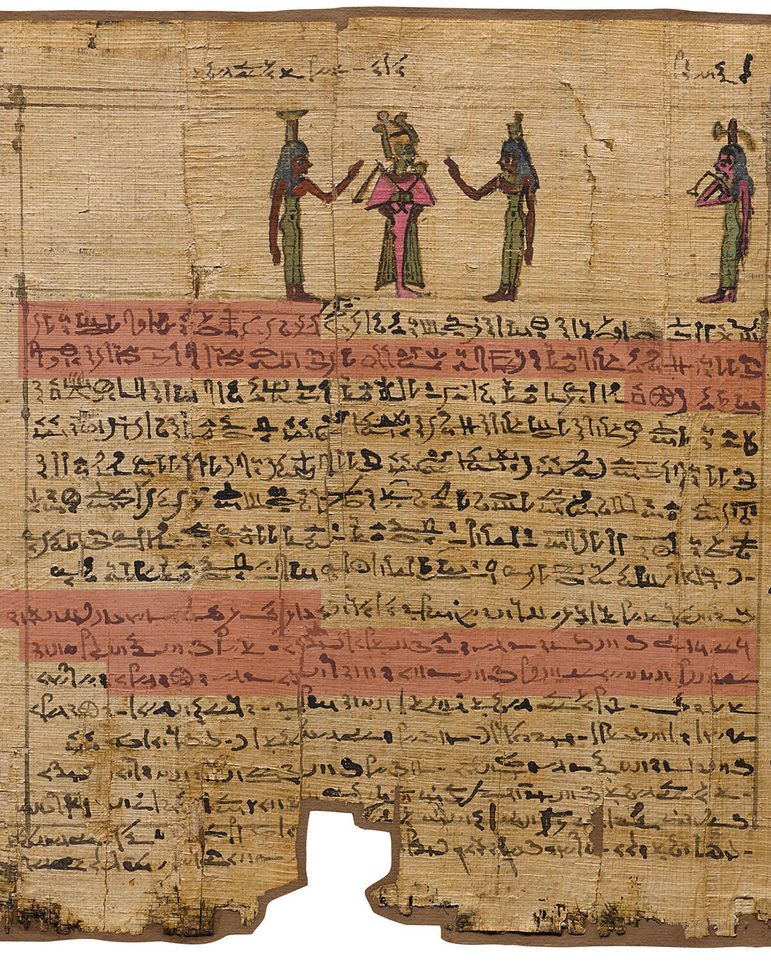

Top: Funerary papyrus of Montsuef. Museum reference A.1956.313. Bottom: Funerary papyrus of Tanuat. Museum reference A.1956.314.

Whose stories do the papyri tell?

The papyri of High official Montsuef and his wife Tanuat are special because they are not standardised like other funerary papyri. They include personalised details about the good lives they led in the hope this would help them reach the afterlife. They note that they they left behind a son and a daughter. They also include details about the mummification process, so they are important sources about the materials used to preserve the body and the rituals involved.

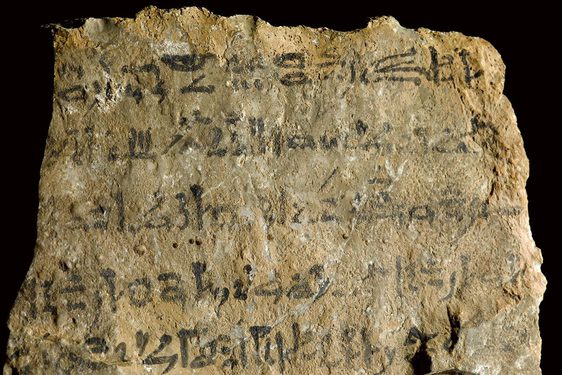

The texts both read right-to-left as was typical of Egyptian papyrus rolls. They are written bilingually in an older, priestly script called hieratic and a later script called demotic. The hieratic script had religious precedent, while demotic was the everyday script used at the time. Using the two scripts would have made the text more accessible. Some parts were intended to be read aloud by priests during the mummification rituals, and others addressed the deceased directly. One section instructs Montsuef to recite a speech claiming his innocence of any wrongdoing, which he may have been able to read himself.

The papyri were part of a Roman-era family burial that was excavated by Alexander Henry Rhind. Montsuef and Tanuat and several of their family members were buried there until it simply fell out of use. Having their deaths in 9 BC recorded on their papyri allows us to date the other objects found in the Rhind Tomb.

Montsuef’s Papyrus

Montsuef's papyrus is personalised with details of his life. Montsuef held the honorific title 'kinsman of the king’, denoting his elite status, and he served as a ‘cavalry officer’, which was a high-ranking position in the provincial administration. His father Menkaure had held the position of strategos, or governor of the entire province. The family was based at the provincial capital of Hermonthis (modern Armant), twelve miles south of Thebes.

Seven key images and passages have been described and translated to help us understand Montsuef’s life and death.

1. The life of Montsuef

The text tells us that Montsuef was the son of Menkaure, a priest of the god Montu-Ra, Lord of Armant. Montsuef’s birth date, 4 December 69 BC, is written as:

‘Regnal year 13, the 27th day of Hathor-month, of Pharaoh Ptolemy XII (father of Cleopatra VII).’

Montsuef was 59 years old when he died. He lived through the Roman conquest of Egypt, so the date of his death, 4 July 9 BC, is written as:

‘Regnal year 21 of Caesar Autocrator (Roman Emperor Augustus), the 10th day of Epip-month.’

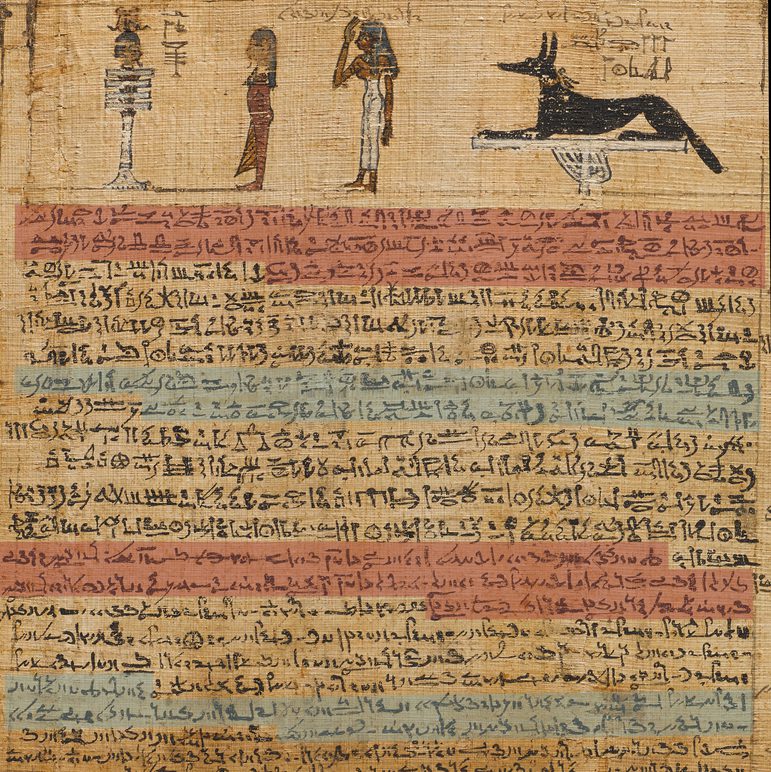

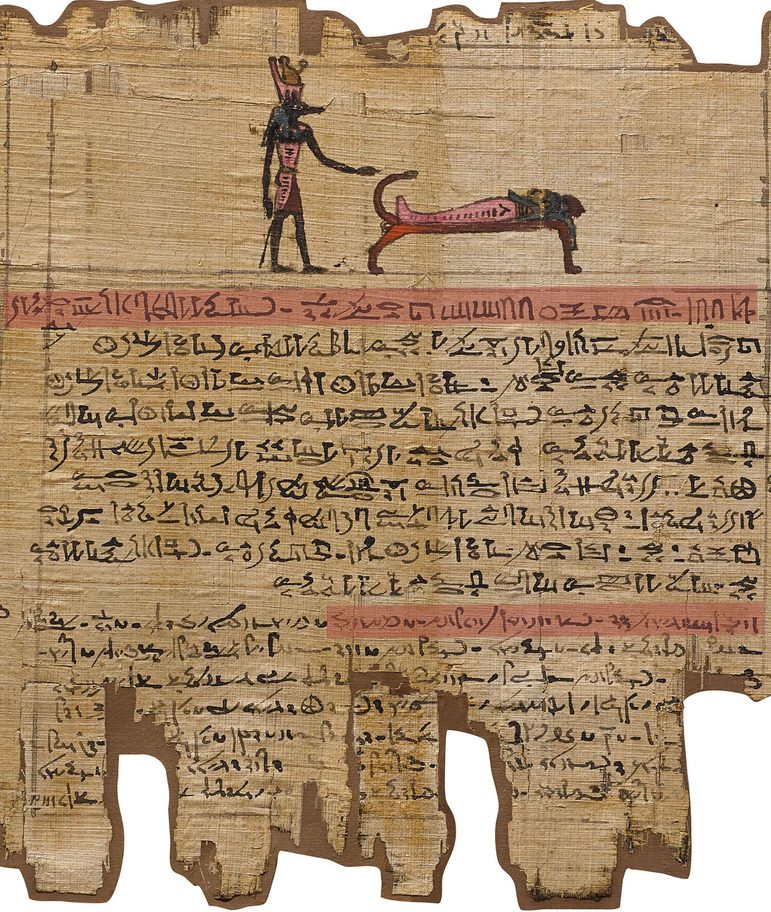

Column 1 of the funerary papyrus of Montsuef, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic. The second quotation is highlighted in blue.

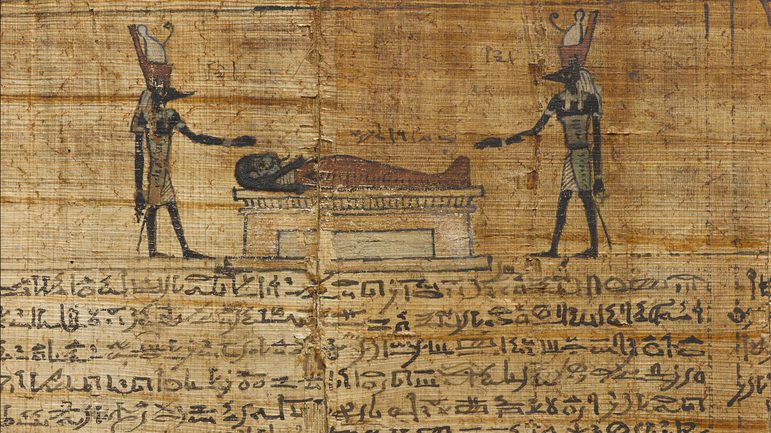

2. Anubis speaks to Montsuef

This image shows Montsuef lying mummified between two jackal-headed figures: embalming priests wearing masks to play the role of Anubis, god of mummification. Montsuef wears a style of beard usually worn by gods. His skin is green, the colour of growth and rebirth associated with Osiris, king of the afterlife. The text provides a speech for the embalming priest.

3. Anointed with oil by Horus

The text tells us about the rituals performed for Montsuef during the mummification process and what materials were used:

‘17 processions will be made for you within the 70 days of mummification.’

‘103 litres of sacred ointment will be boiled for you, like that which is prepared for sacred bulls. You will be anointed with oil by Horus.’

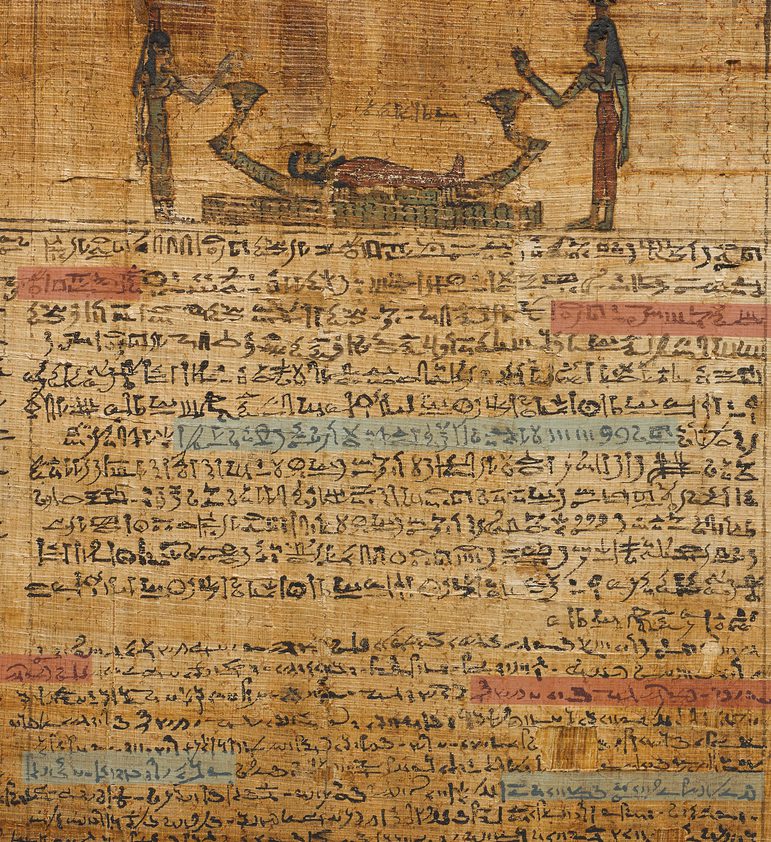

Column 3 of the funerary papyrus of Montsuef, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic. The second quotation is highlighted in blue.

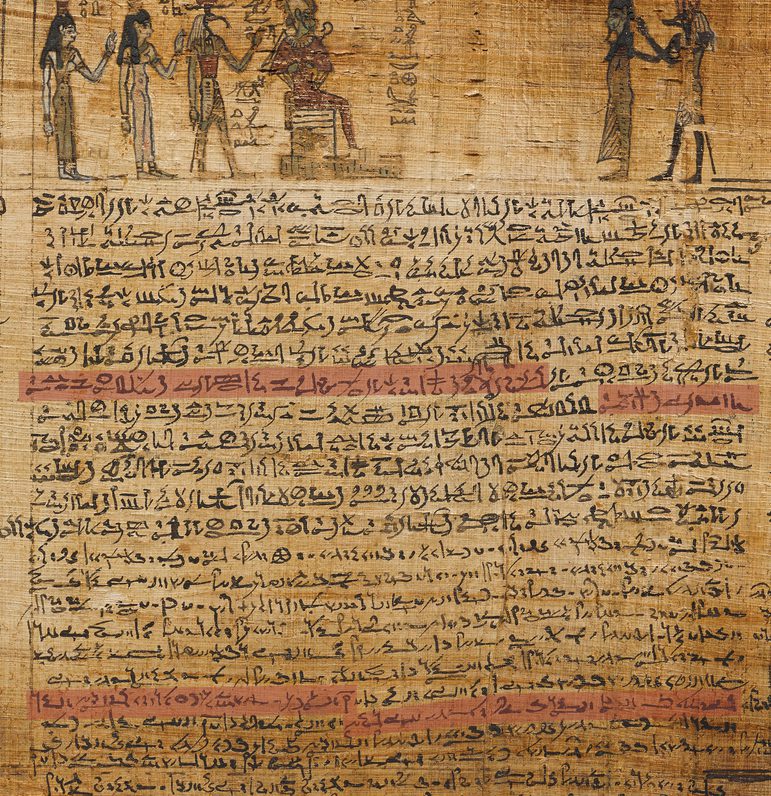

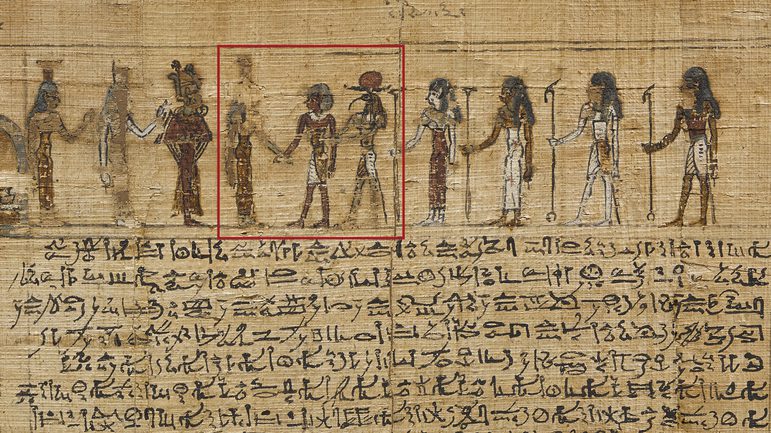

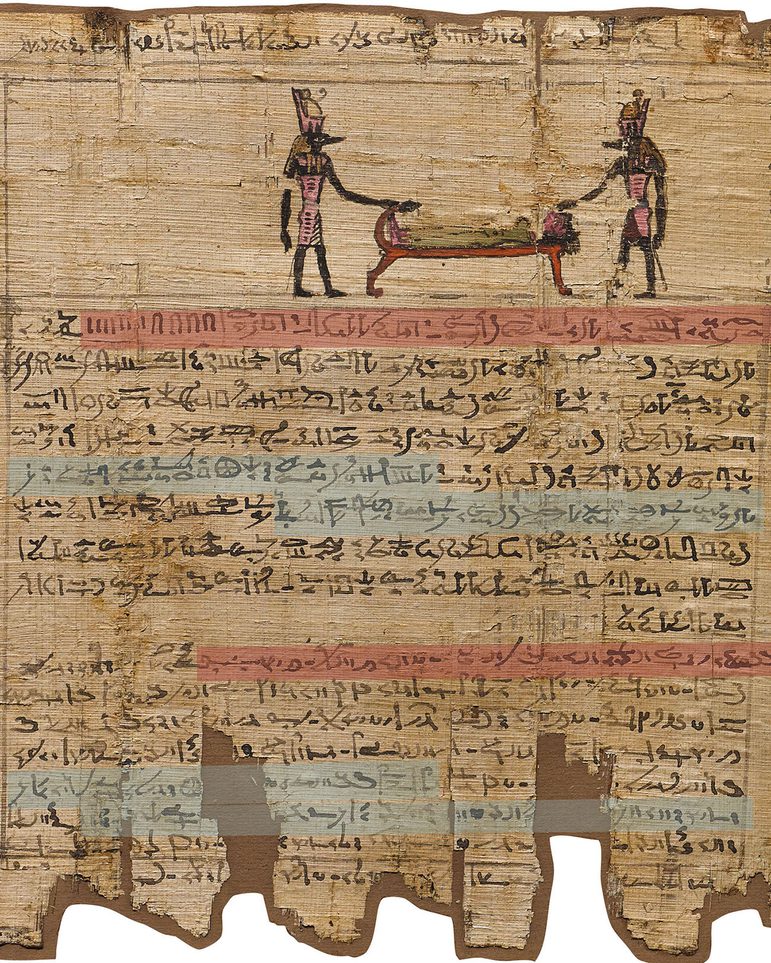

4. Presentation to Osiris

This image shows the jackal god Anubis presenting the mummified Montsuef to Osiris, seated on a throne, followed by Thoth, Isis and Nephthys.

The text tells us about the good life Montsuef lived:

‘You passed your lifetime on earth having a full measure of every good thing that your heart desired, no man having become poor because of you and without having done a misdeed.’

Column 4 of the funerary papyrus of Montsuef, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic.

5. Speeches to Osiris

The first selection of text tells us Montsuef was a good man:

‘O one who has died and gone to the West, you grew old on earth in a happy life. Do not let worry be in your heart. Small children go to the West, but you reached a great age on earth. You drank and ate there. You did all that your heart desired and everything was spread out before you. “No” was not said in your presence on any day.’

The second selection of text tells Montsuef what to say to Osiris:

'Call out in a loud voice: O my lord, my father Osiris! I am an excellent man who is on the path of righteousness…I have not committed a sin, your abomination, in my lifetime… I gave bread to the poor.’

Column 7 of the funerary papyrus of Montsuef, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic. The second quotation is highlighted in blue.

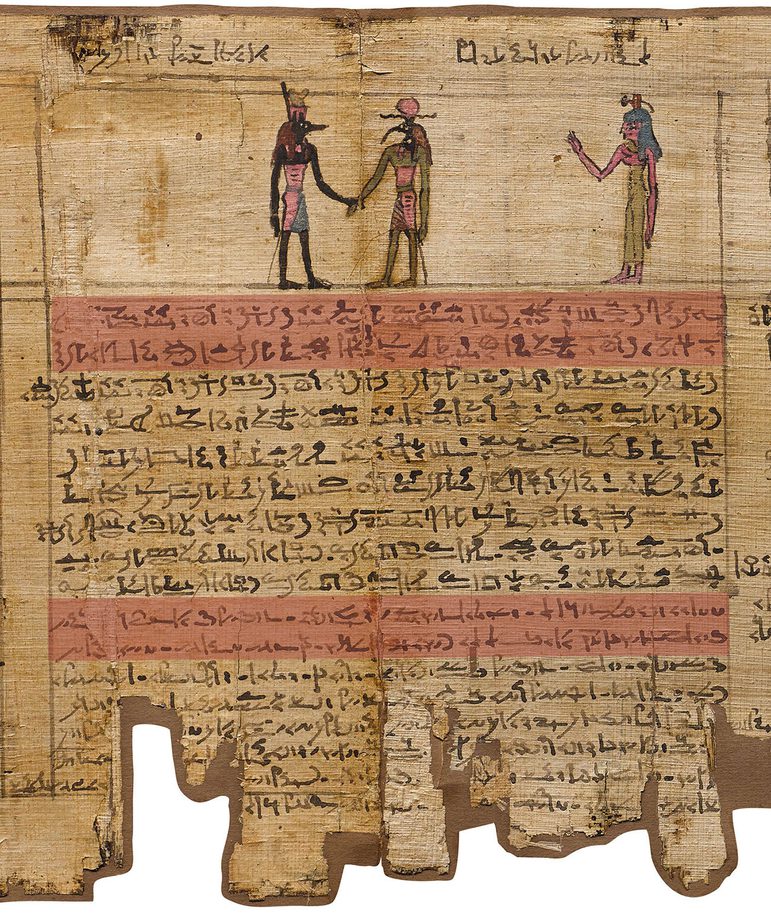

6. Presentation to Ma’at

The image shows Montsuef being presented to Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice, by the god of writing Thoth. Thoth records the verdict on the judgement of Montsuef. The text derives from an ancient funerary ritual that was over 2000 years old when this papyrus was written.

The Opening of the Mouth ritual was used to reawaken the senses. The eyes, nose, mouth and ears were touched while an appeal to the gods was recited, ‘May you establish his heart in his body. May you open his eyes for him. May you open his mouth for him. May you open his nostrils for him.’

Column 10 of the funerary papyrus of Montsuef, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. The image shows Montsuef being presented to Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice, by the god of writing Thoth.

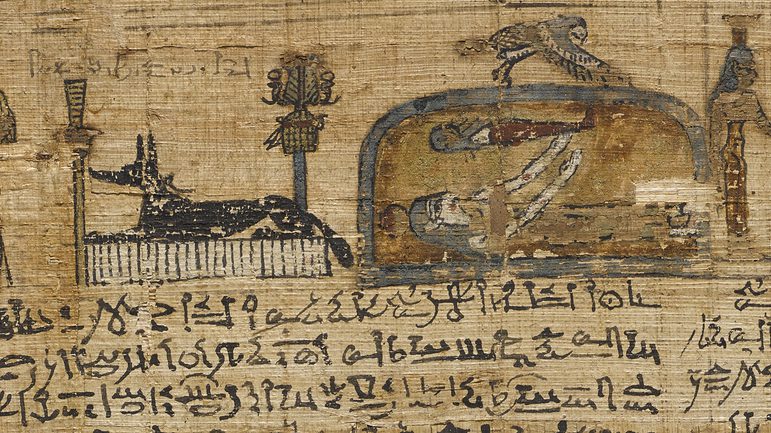

7. Montsuef’s spirit leaves the body

Montsuef is shown lying in his sarcophagus in the protective embrace of the sky goddess, Nut. Montsuef’s spirit is shown leaving his body in the form of aba-bird. The jackal god Anubis guards the cemetery.

Column 11 of the funerary papyrus of Montsuef, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC.

Tanuat’s Papyrus

Tanuat’s papyrus is a shortened version of her husband’s and the spells are adapted to suit her. A key difference is Tanuat is referred to as ‘the Hathor Tanuat’, referencing the female counterpart to the funerary god Osiris, to ensure the preservation of Tanuat’s gender.

Six key images and passages have been described and translated to help us understand Tanuat’s life and death.

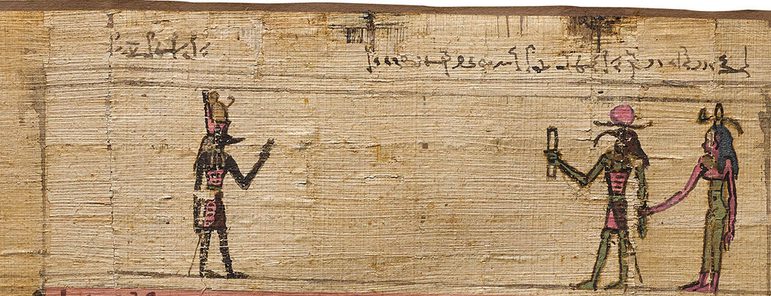

1. A protective papyrus for Tanuat

The illustration depicts Tanuat with the ibis-headed god of writing, Thoth. The inscription says Thoth wrote this papyrus to serve as protection for Tanuat.

Tanuat’s birth date, 31 May 62 BC, is written as ‘Regnal year 19, the 26th day of Pakhons-month, of Pharaoh Ptolemy XII (father of Cleopatra VII)’.

The date is described as ‘the happy day of the birth of a good woman’, the daughter of ‘a great leader named Kalasiris’.

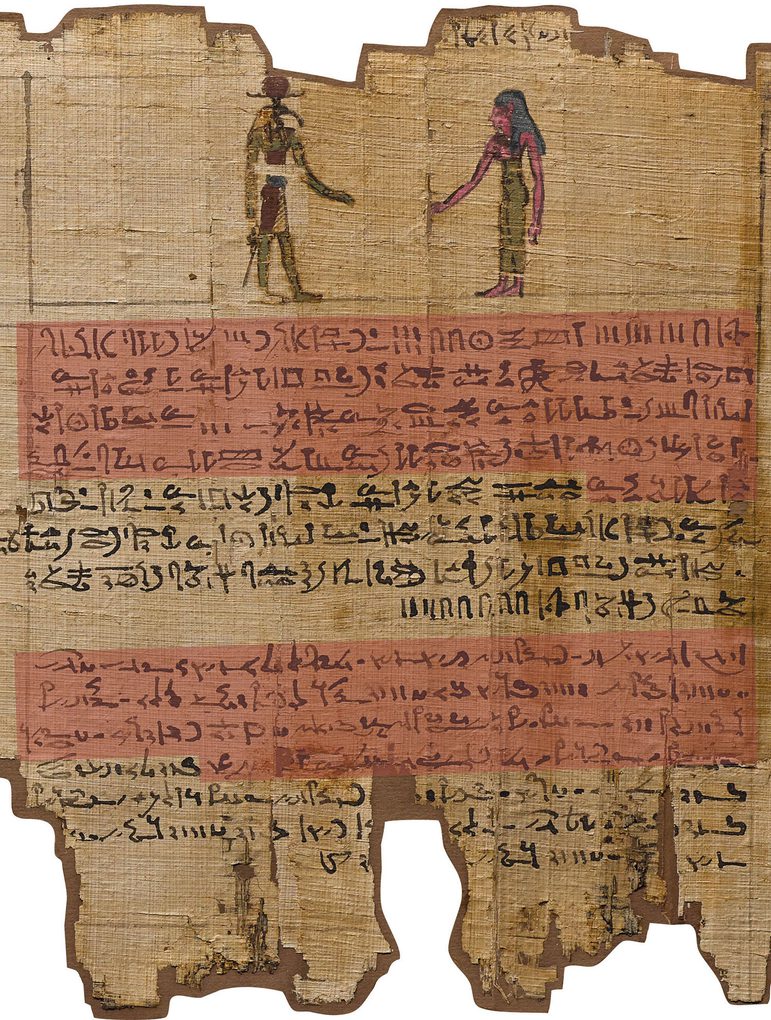

Column 1 of the funerary papyrus of Tanuat, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic.

2. The life and death of Tanuat

Tanuat was 54 years old when she died, just 48 days after her husband.

The date of Tanuat’s death, 21 August 9 BC, is written as ‘Regnal year 21, the 28th day of Mesore-month, of Caesar Autocrator (Roman Emperor Augustus).’

Column 2 of the funerary papyrus of Tanuat, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic.

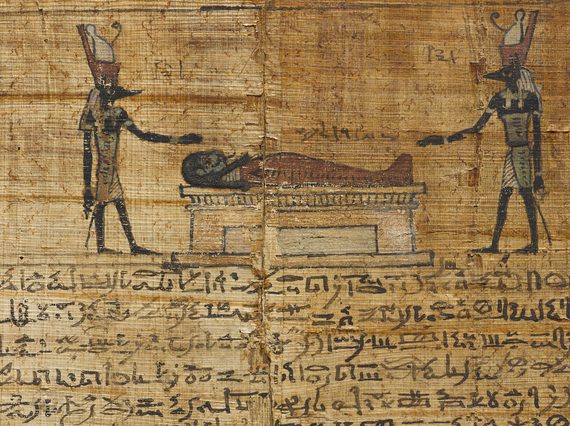

3. The mummification of Tanuat

Tanuat is shown lying on a mummification bed. The two jackal-headed figures represent Anubis, the god of mummification. Priests who performed the embalming sometimes wore a jackal-mask.

The text says that Anubis will ‘will revitalise your flesh. He will make your skin whole. He will cause your skeleton to be firmly held together.’

Column 3 of the funerary papyrus of Tanuat, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC.

4. Tanuat transformed

Tanuat is shown transformed into a sanctified being. On her head, she wears a lotus-flower, a symbol of rebirth, and a cone of fragrant perfume. She is addressed as ‘the Hathor Tanuat’, to associate her with Hathor, the goddess of fertility, and ensure her rebirth.

The text says: ‘‘May you come, content, one of the happy women, to the necropolis of Djeme (the West Bank of Thebes), having completed your span of living a pleasant life on earth. You left a son and daughter behind you, one succeeding another in the house of your father.’

Column 6 of the funerary papyrus of Tanuat, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic.

5. An illustrator’s error

Captions written at the top of the papyrus were instructions for the illustrator. Sometimes errors were made. Here the caption above Anubis says ‘a figure of Osiris’.

Detail of column 7 of the funerary papyrus of Tanuat, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC.

6. A good woman enters the afterlife

In the text, the god Osiris says ‘This woman whose heart is humble, let her be among the noble women who follow Osiris. Let her ba-spirit be rejuvenated together with their bas. Let her body endure in the afterlife.’

The text says that Tanuat will be praised because of ‘the greatness of her virtues’ and her ‘good deeds will be recited in the presence of Osiris’, who will favour her eternally.

Column 9 of the funerary papyrus of Tanuat, Thebes, Egypt, 9 BC. When indicating where the text has been translated, the quotation is highlighted in red, first in demotic above, then again below in hieratic. The second quotation is highlighted in blue.

Catch a glimpse of how papyrus is made and discover the conversation work undertaken on these funerary papyri in this short film.