The court arts and history of the Kingdom of Benin

News Story

For centuries highly skilled artists and artisans of the Edo Kingdom have produced outstanding artworks. They are of immense cultural value in the royal city of Benin in present day Nigeria.

The current Oba, or king, belongs to a dynasty that has governed the kingdom from a court centred in the royal city of Benin in south-eastern Nigeria from at least the 13th century. Edo oral history indicates that the kingdom was founded in around the 10th century. It was ruled by a dynasty of kings titled Ogiso, who first established a court in the region of Benin City. The Ogisos also established the beginnings of the palace craft guilds. This led to the development of the kingdom’s unique artistic traditions in ivory, wood and metal.

In about 1200 CE, the Ogisos are said to have been replaced by the current dynasty. Prince Oranmiyan from the neighbouring kingdom of Ife was invited to take the throne at Benin. Oranmiyan soon returned to Ife, but he left a son who took the new title of Oba. This was the highest political and religious authority in the Edo Kingdom.

Conquest and contact

During the 15th and 16th century, Benin expanded its territory through military conquests. At this time, Benin also made contact with Portuguese merchant adventurers on the coast and began to trade with them.

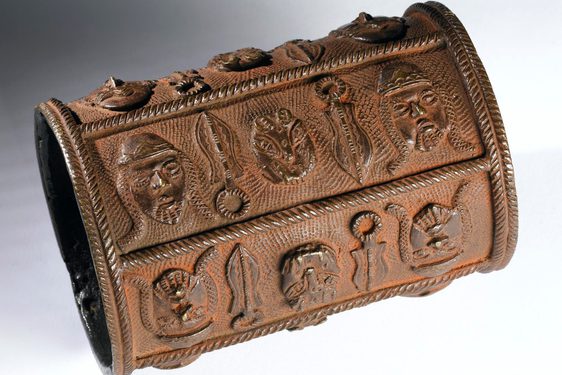

New goods were introduced by Portuguese merchants. This included Indian and European cloth, coral beads, and brass currency bracelets. These were incorporated into works of royal and courtly regalia.

Benin’s royal craft guilds

Guilds of specialist craftspeople were controlled by the palace. These guilds produced a wide range of highly accomplished works for the Oba and his court. This art was central to the ceremonial life of the Edo Kingdom.

Craftspeople created works to mark rites of passage such as birth, marriage, and death. Their work also utilised for the celebration of annual festivals and to honour and commemorate the royal ancestors. The coronation of a new Oba was also marked with works by guilds. Surviving works therefore reflect the cultural and political history of this powerful empire.

Royal commemorative heads

Sculpted heads cast in copper alloys are still important items for commemorative altars dedicated to the royal ancestors. Each new Oba is required to commission a shrine to honour and commemorate his predecessor. This is part of legitimising his own succession.

The heads are made in pairs and placed on either side of an altar. Sacred rattle staffs, bells, and other significant cast figures are placed alongside the heads. Most cast heads have a hole in the top, which served to hold an elephant tusk. The tusks were richly carved with relief images relating to the deceased Oba’s royal authority and personal achievement.

Commemorative head of an Oba (King) made of cast brass/bronze. West Africa, Nigeria, Edo State, Benin, 18th to 19th century. Museum reference A.1898.381.

In Edo philosophy the head is the seat of a guiding spiritual force. It is associated with a person’s destiny and judgement, as well as his or her knowledge, intelligence, character, and leadership. Stylised commemorative altar heads are therefore powerful visual references to the spiritual authority and success of past Obas. The physical and spiritual strength of the reigning Oba is connected with the well-being of the entire kingdom. Royal ceremonies are performed in Benin City each year to spiritually strengthen the Oba.

The style of cast altar heads changed over time. Art historians have developed a timeline which recognises eight stylistic variations of heads dating from around 1400. National Museums Scotland’s collection includes a later commemorative head. It dates stylistically from the 18th to 19th century. It can be dated by the presence of winged elements on each side of the cap, and a flanged base richly decorated with royal symbols of leopard, mudfish, and the heads of sacrificial animals. Like the older style heads, details include multiple rows of coral beads around the neck and a coral bead cap, worn as symbols of kingship to the present.

Benin under colonial rule

During the second half of the 19th century, the Edo Kingdom was weakened by conflicts over succession. It lost some of its military, political and economic power. At the same time, British imperial ambition for control over west African markets and territories led to increased pressure on the Oba to open the Edo Kingdom to ‘free trade’ with British commercial firms. The invasion of Benin by British troops in 1897 resulted in the removal and exile of the reigning Oba Ovonramwen. He was replaced by British overrule.

Following the death of Ovonramwen in exile in 1914, his son was crowned Oba Eweka II. He reigned with limited powers under British supervision. Eweka II rebuilt the royal palace and restored the craft guilds. He set up the Benin Arts and Crafts Council to produce artworks for new external markets.

At Nigerian Independence in 1960, the Edo Kingdom was incorporated into the Nigerian state. Successive Obas from the kingdom’s ruling dynasty have retained their title and many cultural practices. The monarchy and its court rituals still provide a political and cultural focus in Benin City for Edo-speaking people.

There are several objects from Benin on display in the World Cultures galleries in the National Museum Of Scotland.