6 world-class type specimens in our stores

News Story

Type specimens are among the most important objects in natural science collections. They are the specimens on which the scientific names of species of animals, plants or minerals are based.

Animals and plants are named using the Linnaean system of binomial nomenclature and are given a genus and species name, e.g. ours is Homo sapiens. Each species' Latin name describes a unique feature, or where it was found or who found it.

The original description in a scientific publication must explain the unique features that make it different from any other species along with an illustration of the type. For fossils, additional specimens found subsequently and figured in scientific publications may be more complete or better preserved than the type and show additional features.

For animals, if there is only one specimen then that is the holotype. Additional specimens mentioned in the description can be paratypes. If several specimens are described together, they are syntypes. Sometimes the best syntype specimen is later selected as the main type and is called a lectotype. Sometimes type specimens are lost or destroyed (e.g., wars, fires, floods), so that a replacement neotype may be chosen.

1. Siberut macaque, Macaca siberu

Charlie was a macaque monkey that lived at Bristol Zoo from 1976 to 1997. He was preserved as a study skin and skeleton registered at National Museums Scotland. Charlie was originally identified as a Mentawai Island macaque, Macaca pagensis.

Macaca pagensis is found only on the Mentawai Islands of North and South Pagai, Sipora and Siberut off the coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. They were described as a new species in 1903. In 1995, field researchers Agustín Fuentes and Monica Olson noticed that that macaques from Siberu looked different from those from the other islands. Researchers gave the Siberut macaque a new name as a subspecies, Macaca pagensis siberu, based on Charlie and a study skin in the Natural History Museum in London.

In 2002, it was recognised that the Siberut macaque was so distinct, it is in fact a separate species. The new species was named Macaca siberu, and Charlie was selected as the lectotype.

Skull of adult Charlie the Siberut Macaque. Museum reference Z.1999.24.

2. Goodman’s mouse lemur, Microcebus lehilaytsara

In 2005, Zurich Zoo imported nine mouse lemurs from Andasibe Province Taomasina, Madagascar to release into their huge new Madagascan rain forest exhibit, Masaola. Originally identified as rufous mouse lemurs, Microcebus rufus, genetic tests showed that they were a new species. They were named Microcebus lehilaytsara, Goodman’s mouse lemur, by Christian Roos and Peter Kappeler just a few months after their arrival.

One female died later in 2005. In 2015, she was donated to National Museums Scotland, where she is preserved as a skin and a skeleton and registered as Z.2015.180. She is one of nine syntypes for this species.

Type specimen of Goodman's Mouse Lemur. Museum reference Z.2015.180.

3-4. Macphersonite and Mattheddleite

The Earth System section looks after thirteen official type mineral specimens. One of these is especially unusual: it contains two distinct type minerals within a single specimen.

This rare type specimen includes both Macphersonite and Mattheddleite on the same small sample.

Macphersonite is a pale green, resinous crystal located at the centre of the specimen. Mattheddleite is the best observed under a microscope. It is the fine, slender, needle-like crystals that are white to transparent, covering the other minerals.

The sample was found at Leadhills Dod, Leadhills, Lanarkshire. This specimen was originally acquired because it contained a fine example of the mineral Leadhillite (a hydrated lead sulfate carbonate mineral). One hundred years later, two rare new minerals were discovered on the specimen.

Minerals are defined by their chemical formula. Macphersonite is Pb₄(SO₄)(CO₃)₂(OH)₂. This means it’s a hydrated lead sulfate carbonate. Mattheddleite’s formula is Pb₅(SiO₄)₁.₅(SO₄)₁.₅Cl, known as a lead silicate sulfate chloride.

Both minerals are named after people who worked at National Museums Scotland. Matthew Forster Heddle was a Scottish physician and amateur mineralogist who was active through the 19th century. Heddle contributed a third of our Scottish collection and designed the 1895 Scottish mineral gallery.

Dr Harry G. Macpherson was at one time, Keeper of Geology. Both minerals were discovered by Alec Livingstone, a curator of mineralogy at National Museums Scotland.

As of August 2025, scientists have identified just over 6,100 mineral species. Each newly recognized mineral must have at least one designated type specimen - the reference sample used to describe and define it. In most cases, two or three specimens are preserved in different institutions for security and study.

On average, just over 100 new mineral species are discovered each year. Eventually, the total number of known minerals on Earth – including those found in meteorites – is expected to exceed 9,000.

Sample of Macphersonite and Matheddite. Museum reference: G.2019.25.4979.

5. A fossil invertebrate from Carlops, Eoghanspongia carlinslowpensis

Our Palaeobiology collection contains many type specimens of fossil animal and plant species. New species are regularly being described. The animals are divided into vertebrates (those with backbones, e.g. fish) and invertebrates (without backbones, e.g. molluscs).

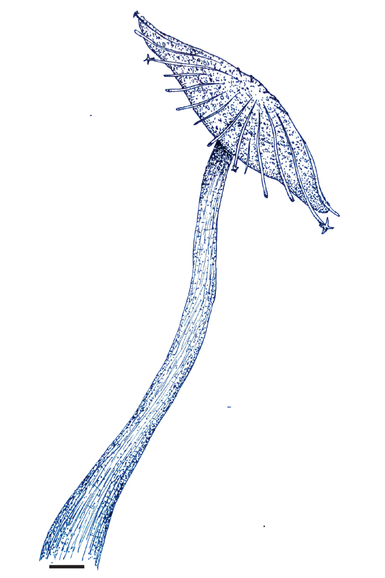

Specimen G.2010.38.1 is an example of a fossil invertebrate type. It is the holotype of a fossil sponge that was named Eoghanspongia carlinslowpensis. It's named after the Scots name for the town of Carlops (Carlin Lowps), the closest town to where it was found in the Pentland Hills. Important fossils of Silurian age, dated as 438 – 433 million years old, have been collected from the Pentland Hills since the first half of the 19th century. Though this particular species was only discovered 15 years ago.

The fossil sponge has an unusual, umbrella-like morphology. It contributes to the uniqueness of the fossil sponge fauna from the Pentland Hills, as nothing like it has been found anywhere else in the world. In 2019, it was named in a scientific paper.

The holotype of fossil sponge Eoghanspongia carlinslowpensis. Museum reference G.2010.38.1.

A reconstruction of how Eoghanspongia carlinslowpensis probably looked in life.

6. A fossil vertebrate ‘Lizzie’, Westlothiana Lizziae

In the 1980s, a very important fossil vertebrate type was discovered in Scotland. It was named Westlothiana, after where it was discovered in East Kirkton quarry, Bathgate, West Lothian.

The fossil got its nickname 'Lizzie' because it looked so lizard-like. But don't let the name fool you. It was thought to be the oldest known reptile, but ‘Lizzie’ is not actually a lizard and it is impossible to tell if ‘Lizzie’ was a female.

Read more about Lizzie.

Fossil remains of Westlothiana Lizziae. Museum reference G.1991.47.1.1.

Across Natural Sciences, our collections and specimens are open to researchers for examination. We'd be happy to help you conduct research. Please contact our staff to enquire.