Wylam Dilly: One of the world's oldest locomotives

News Story

Wylam Dilly is one of the world’s two oldest surviving locomotives. Built in 1813, it used to pull coal along the Wylam Wagonway to the river, near Newcastle upon Tyne.

The Wylam Dilly steam locomotive is named after the Wylam Colliery, where the locomotive was used. A colliery is a coal mine and its associated surface buildings, and a ‘dilly’ was the name of the coal trucks used on the wagonway.

Previously, the job of pulling coal along the wagonway had been done by horses. But a growing demand for coal in the 1800s meant that colliery managers and owners needed a quicker way of getting coal to their customers.

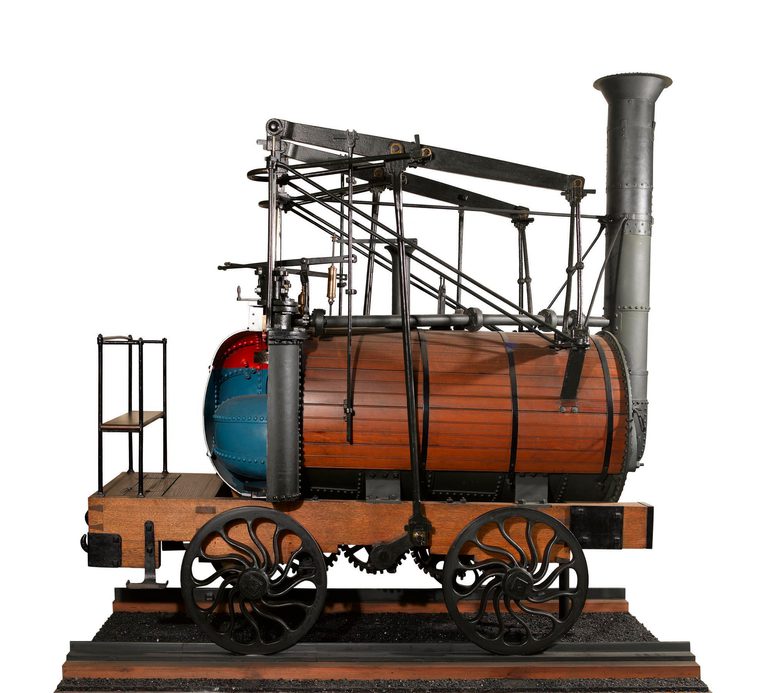

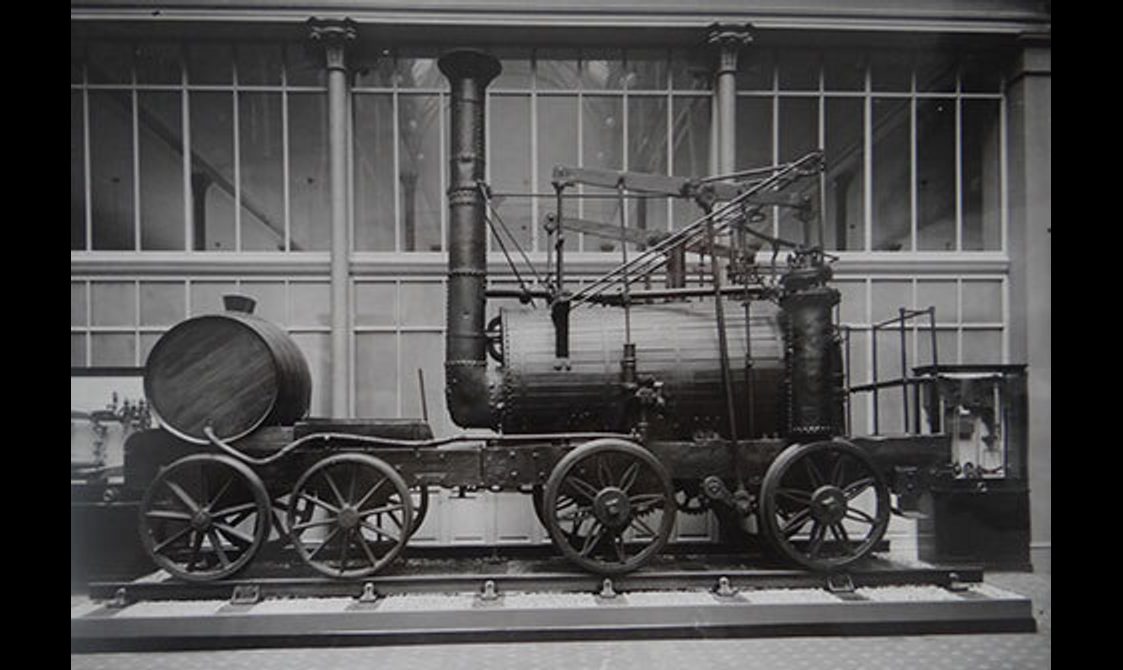

Model of Wylam Dilly. Museum reference T.1885.227

Inventing the locomotive

In the early 1800s a number of people were trying to find new ways of using steam power, especially for moving goods from one place to another. The most famous name associated with steam power is Stephenson.

The ‘father of the locomotive’, George Stephenson (who was born in Wylam and worked briefly at the colliery) finished work on his first locomotive, ‘Blücher’, in 1814. His son Robert Stephenson’s most famous engine, ‘The Rocket’, built in 1829, set the blueprint for locomotives for the next 150 years. The original is in the Science Museum, but you can see a working model at the National Museum of Scotland.

Working model of Stephenson's 'Rocket'. Museum reference T.1937.59.

Before George Stephenson, industrial engineer William Hedley was also looking at how steam power could be used in his work. William Hedley was born in Newburn, west of Newcastle upon Tyne, in 1779. In 1805 he was appointed as Colliery Manager of the Wylam Colliery. Soon after his appointment, an engineer at the nearby Middleton Colliery invented a new locomotive. It used gears meshing on a toothed rack laid between the rails to haul itself along.

Hedley’s locomotive

In 1812 William Hedley began to design and build his own steam locomotive which would run along the Wylam Wagonway.

Hedley’s locomotive would be designed to run on smooth rails rather than using a rack between the rails. In 1812, Hedley had proved by experiment that a locomotive could pull wagons which were heavier than the locomotive without using racked rails. This was a feat which had previously not been thought possible.

By 1813 Hedley had built his first locomotive, and a second was underway. These two locomotives were Wylam Dilly and Puffing Billy.

Wylam Dilly with Hedley’s sons William and George, photographed between 1869 and 1882.

Wylam Dilly takes to the water

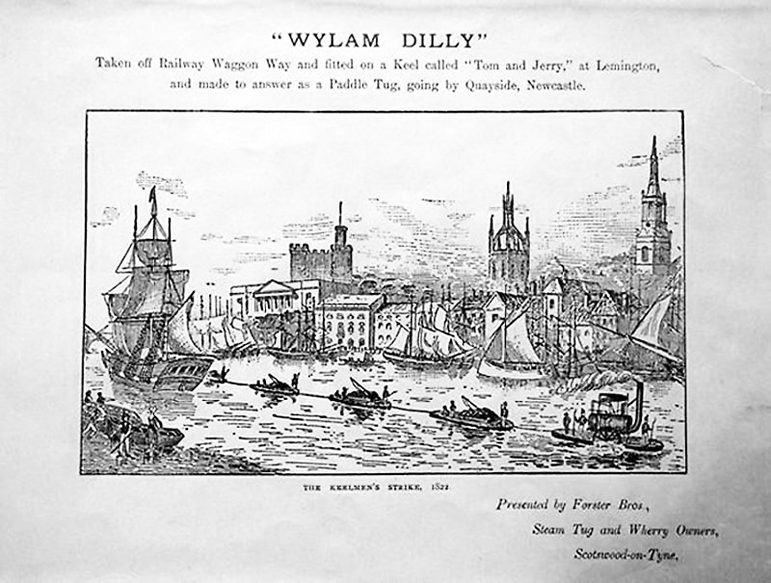

One of the strangest episodes of Wylam Dilly’s history occurred during 1822. Wylam Dilly and Puffing Billy were being used to haul coal from the colliery to the river Tyne. The coal was then off-loaded and put onto keels or small boats to be taken down the river.

In 1822 the keelmen who piloted the small boats went on strike and coal began to pile up on the riverbank. Hedley decided to turn Wylam Dilly into a tugboat, to pull cargo behind the locomotive along the river. This broke the strike.

Wylam Dilly continued to work as a tugboat for some time before being turned back into a railway locomotive.

The amphibious Wylam Dilly pulling cargo along the river.

Wylam Dilly at the Museum

Wylam Dilly worked along the Wylam Wagonway from 1813 until 1882. It worked for 20 years longer than Wylam Dilly's locomotive, Puffing Billy, who was sent to the Science Museum in 1862.

During its 70 years of service, Wylam Dilly was adapted many times. One major change was that the locomotive was given eight wheels instead of four, so the weight of the engine would be spread more evenly.

When the colliery closed, Wylam Dilly was bought by two of William Hedley’s sons, who gave the locomotive to the Museum in Edinburgh in 1882. Wylam Dilly has been in the Museum ever since, except for a short trip in 1890 to be displayed in the Edinburgh International Exhibition of Electrical Engineering.

Image gallery

Wylam Dilly in present day. Museum reference T.2002.38

Wylam Dilly on rails before coming to the museum in 1882.

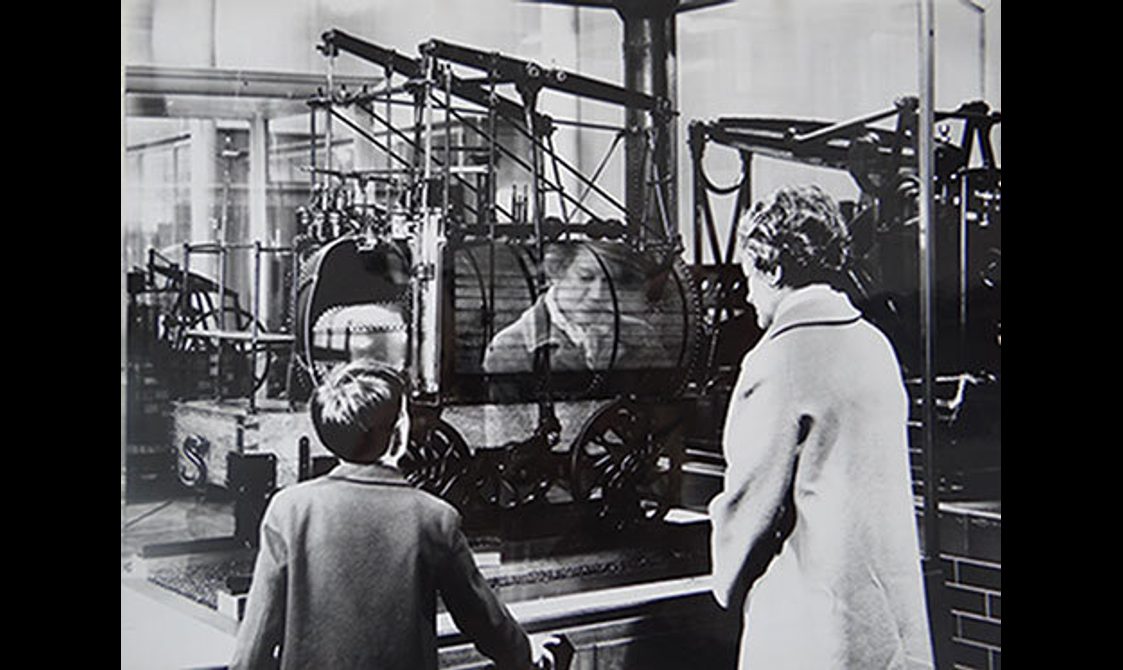

Archive photo of Wylam Dilly on display in the 'Hall of Power'.

This archive photo shows the working model of the Wylam Dilly on display in the 'Hall of Power' in the Museum.