The mysterious 15 million year gap in our evolution

News Story

If the first four-legged animals had never emerged from water onto land, our world today would not exist. Yet how did this great step happen? For decades, scientists didn’t know. Now, the mystery is finally being solved – and fossils discovered in Scotland lie at the heart of the story.

The Earth is approximately 4.6 billion years old, and our story starts 360 million years ago.

Scotland, 360 million years ago

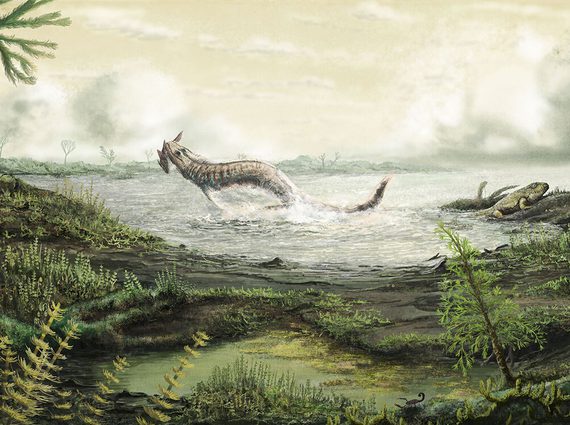

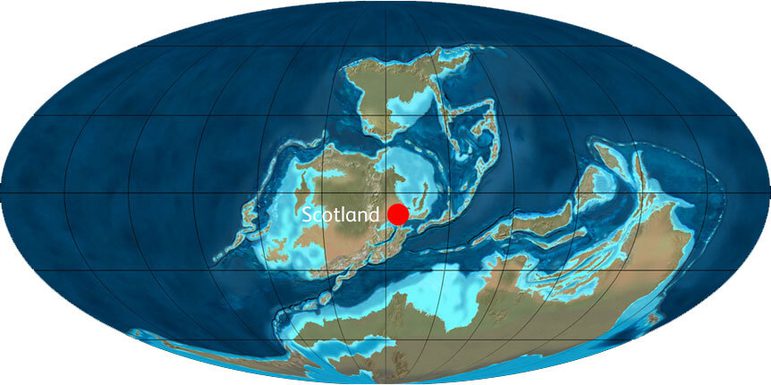

360-345 million years ago, Scotland was a very different place. Lying close to the equator, the vegetated land was hot, humid, and subject to droughts and flooding. It was in this setting that a major evolutionary event occurred; tetrapods (backboned animals with four limbs) invaded land.

For many years, scientists had no idea how this had happened. There was a 15 million year ‘gap’ in the fossil record. Very few tetrapod fossils from this period had been found, so there was no evidence to show how this giant step had taken place.

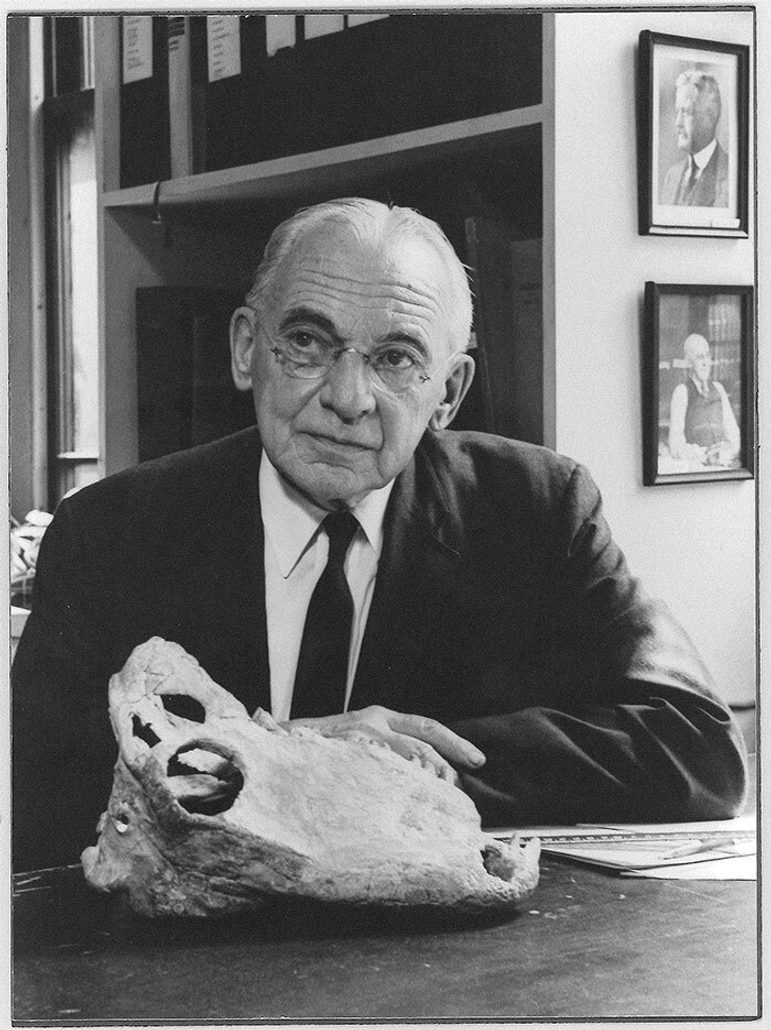

Harvard professor Alfred Sherwood Romer (1894-1973) identified this hole in the fossil timeline. So it became known by scientists as ‘Romer’s Gap.’

Earliest life on land

Long before vertebrates evolved legs, there was already life on land. Fossil evidence includes 475 million year old fossil spores of liverwort-like plants, and a 425 million year old air-breathing millipede from Stonehaven.

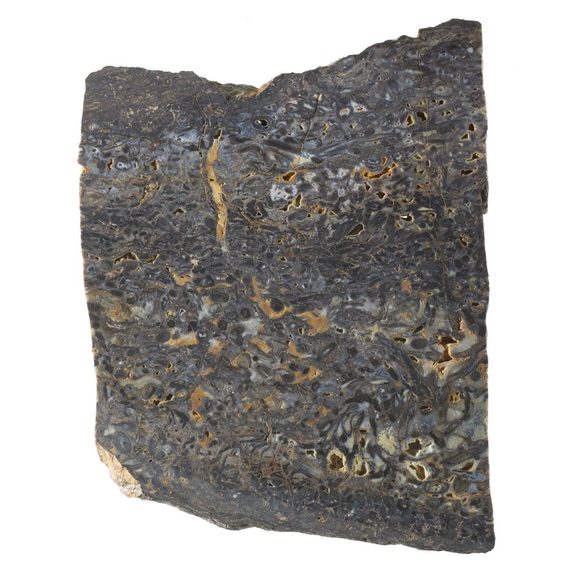

Scotland has evidence of the first terrestrial ecosystem in the world. It was preserved in a bed of sediment called Rhynie Chert, in Aberdeenshire. This 410 million year old rock is made from silica (the same material as glass), and was formed from hot volcanic springs. It contains plants with beautifully preserved cells, primitive spiders, and the oldest known fossil insects. A fungus was also living at that time that grew up to 9m tall!

Yet there was no evidence of tetrapod life on land.

Fish fingers

There were, however, tetrapods living in the water. Fossils show that they had four limbs, and looked as though they should be equipped for life on land. But the limbs of these animals were not adapted to support them out of water. Their feet had as many as eight toes, and scientists now believe they used their legs to crawl along lake and river beds.

But how did these ‘fish with legs’ become adapted to life on land during Romer’s Gap?

Made for walking

Fast forward past the Gap, and there is ample evidence of tetrapod life on land. The earliest tetrapod fossils found after Romer’s Gap show that amphibians were well adapted to walking on land. These new animals had long, slender limb bones and had evolved the ability to breathe on land. They also had a maximum of five toes on their feet. This basic foot pattern has remained with every form of tetrapod since, from reptiles to humans.

Some of the best-preserved fossils of animals from this period were found in Scotland, in particular from the East Kirkton Quarry in West Lothian.

But how had the pre-Gap water-dwellers evolved into these almost reptile-like land lubbers? Without fossil evidence from the Romer’s Gap period, nobody knew.

Finding the missing fossils

Scientists had been trying to unravel to the mystery of the Gap since it was first identified in the 1950s. Some believed that oxygen levels were too low for tetrapods to survive on land, so they thought they simply hadn’t existed. Stan Wood (1939-2012), a self-taught Scottish field palaeontologist, was not so sure.

Stan had found many important fossil sites during five decades of searching. This included the site at East Kirkton Quarry where the earliest post-Gap tetrapods were discovered.

His friend and colleague Tim Smithson had promising, but incomplete, evidence that tetrapod fossils could be found at the Scottish Borders. Stan and Tim began investigating at several sites across the area. These sites, especially Willie’s Hole at Chirnside, contained a diverse range of fossils including fishes, scorpions, and plants. Eventually, they discovered tetrapod fossils dating from within Romer’s Gap. Part of the missing chapter had been found.

Remarkable discoveries

Spurred on by Stan's discoveries, scientists went to the site at Willie’s Hole, hoping to find more evidence of tetrapod life on land. What they found was truly amazing.

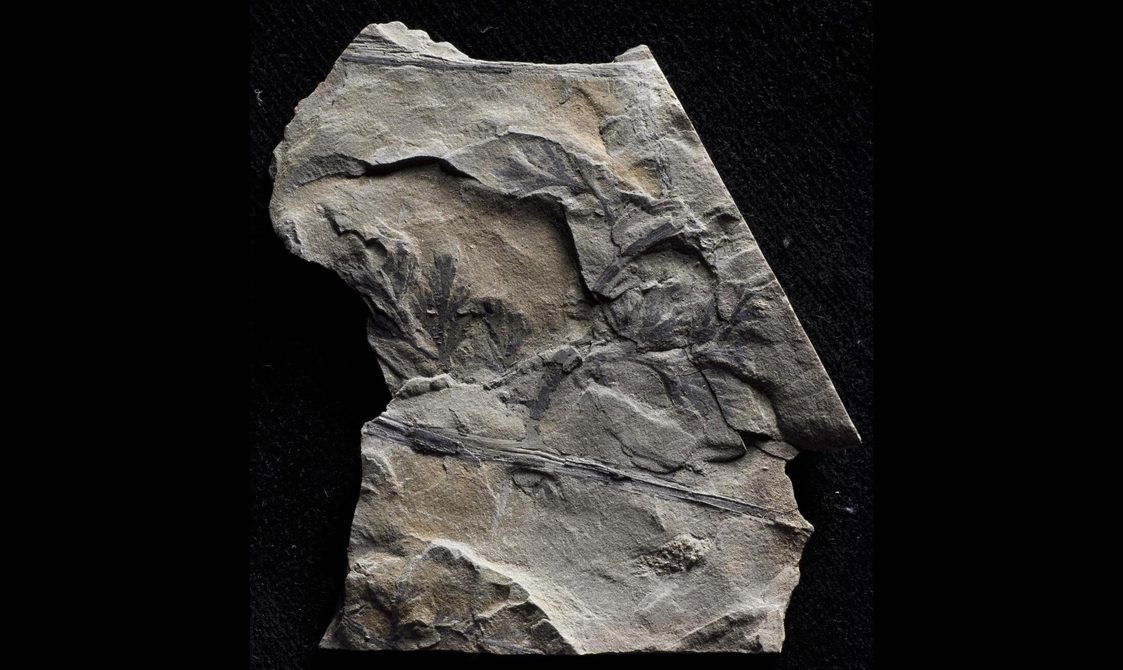

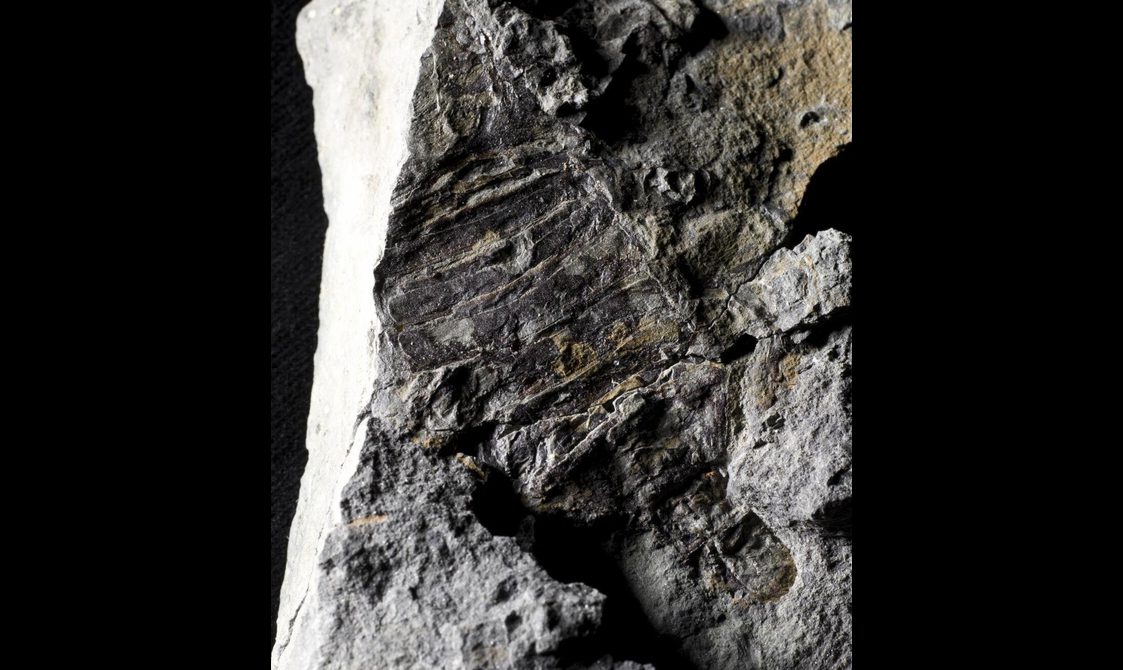

Buried within the river bed were remarkably complete fossils of animal bones, surrounded by fossilised plants and arthropods such as millipedes and scorpions. Such a complete ecosystem, alongside unique evidence of early land-based tetrapods, had never been seen before.

These fossils allow scientists to piece together the world and environment of the early amphibians, and they give us important clues about the mystery of the tetrapod journey from water to land.

Image gallery

The missing tetrapods

The Romer’s Gap tetrapods found in the Scottish Borders are extremely diverse. A wide range of body sizes were discovered. This includes large tetrapods such as ‘Ribbo’, nicknamed for its large prominent ribs. These discoveries confirm that oxygen levels can‘t have been too low to restrict growth.

Many of the fossils found show changes that would have allowed tetrapods to walk on land. This includes changes in limb structures and evidence for well-developed lungs for breathing out of water. Despite these adaptions, research suggests that their legs were likely still too weak for them to walk without their bodies touching the ground.

Scientists at work

Many of the Romer’s Gap fossils were discovered during a major research project funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). This project ran from 2012 to 2016 and took Stan Wood and Tim Smithson’s discoveries as a starting point. The aim was to discover more about life during Romer’s Gap. Leading experts from across the UK, including scientists from National Museums Scotland took part.

In the summer of 2015, the Museum completed a major excavation at Willie’s Hole. This excavation was unusual because the fossil-bearing rocks they were looking for were at the bottom of a river. The river had to be diverted to allow the scientists to remove the fossils from the bedrock.

Image gallery

The ancient environment

Fossils cannot be understood without placing them in the context of their age and environment. Clues about these can be pieced together from the sediments in which they were found.

Traditionally, mechanical tools or acid were needed to study fossils in rock. These highly skilled processes are usually slow and difficult, and may damage the fossil or leave it in a fragile state.

A newer way to observe hidden fossils has radically altered this process. The use of X-ray CT scanning allows scientists to scan the fossil before creating a digital model. This can then be enlarged and printed on a 3D printer. This technique was used by the NERC team to study the Romer's Gap fossils.

What's next?

Fossils found in Scotland are beginning to answer many of the questions originally posed by the mystery of Romer's Gap.

As Romer's Gap closes, a new gap in our knowledge opens. We still do not fully understand why tetrapods evolved the ability to walk and breathe on land. Will Scotland’s rocks reveal the next stage in the evolution of life on land?