A short history of the mineral leadhillite

News Story

This unexpected story has everything. Scotland's second-highest village, Scottish and French kings, a library, Paris, gold and more!

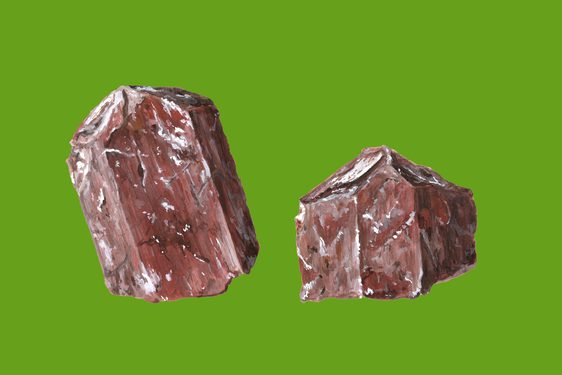

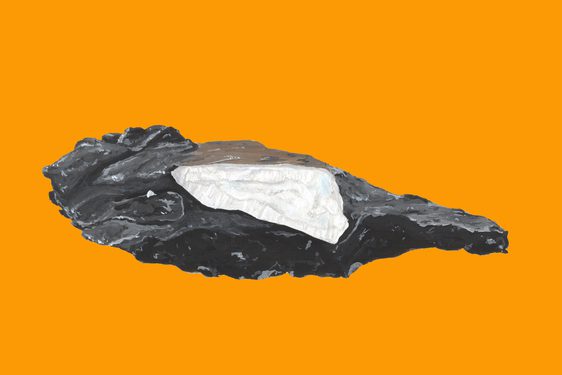

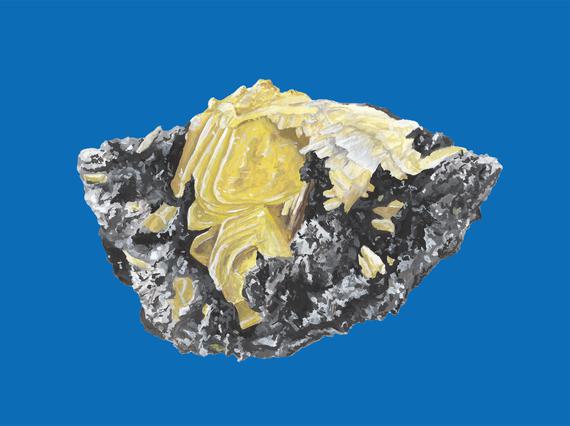

Leadhillite is formed by the alteration of the primary lead ore, here galena, when it was exposed to water, and oxygen near the earth’s surface. It can be colourless, grey, grey-green, yellow, or light blue. It is what mineralogists call a secondary mineral. This means that it is formed by the alteration of the primary lead ore, in this case galena (PbS).

A lead sulphato-carbonate, leadhillite has the chemical formula Pb₄(SO₄)(CO₃)₂(OH)₂. It's named after the village of Leadhills in Lanarkshire, Scotland. The area around Leadhills was perhaps the richest metal mining area in Scotland. It has produced a large number of mineral species, including nine that were first discovered there. Leadhillite being just one of them.

Mining at Leadhills-Wanlockhead was carried out for centuries. Historical documents show that in 1239, King David I of Scotland granted a Charter to the Monks of Newbattle to mine at the locality. Mining may have gone on before this date, but there is only scant archaeological evidence for any earlier activity.

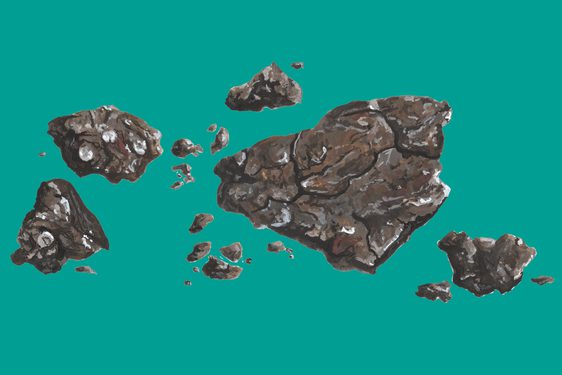

As well as lead, gold and silver were recovered from here. Enough gold was mined at one time to produce coinage during the reigns of James V and Mary. In fact, part of the Scottish Regalia is made from Leadhilll-Wanlockhead gold. Mining eventually ceased altogether in the 1950s after over 700 years.

The village itself grew out of the need to accommodate the miners and their families. But conditions were harsh. Leadhills and Wanlockhead are the two highest villages in Scotland and are frequently cut off by snow. Along with the mining and minerals, Leadhills also has an important place in the social history of the UK. It is the site of the oldest public subscription library in Britain.

The Leadhills Miners Reading Society was set up in 1741 by the miners. They had an entrance fee of 3 shillings (15p) and an annual subscription of 2 shillings (10p). From these monies, books were purchased for the education and benefit of the miners. The library still exists today in the original building. A small museum of lead mining was established in nearby Wanlockhead. The remains of the former mine are still visible, scattered around the countryside.

Despite its clear Scottish heritage, the mineral was first described by a French scientist, Jacques Louis Comte (Count) de Bournon. A refugee from the French Revolution, de Bournon came to Britain in around 1791. He worked on and catalogued the mineral collection of Sir John St Aubyn, a Cornish MP and collector.

de Bournon returned to France in 1814 after the restoration of the monarchy. The new king, Louis XVIII, persuaded de Bournon to sell his collection to the crown. This formed the basis of the Royal Mineral Cabinet, now housed in the Natural History Museum of Paris. In 1817, de Bournon published a catalogue of this collection. In it is the first mention of what was to become leadhillite. There is no indication of how de Bournon obtained these specimens, but they remain in this collection today in Paris.

In 1820, a fuller and more accurate description of this mineral was published by Henry James Brooke in a short paper in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. However, the mineral still had no name at this stage. Brooke called it sulphato-tricarbonate of lead in his paper.

For the first mention of the name leadhillite, we must return to France. In 1832, Francois Beudant, Professor of Mineralogy in Paris, published an important textbook entitled Traité Élémentaire de Minéralogie. In it the name leadhillite first appears referencing the earlier work of Brooke.