Understanding hoards in the Viking Age

News Story

To understand the Galloway Hoard, we need to understand the the world around AD 900. Historical context and comparisons with other Viking-age hoards is essential. We lay out what a hoard is, how historians and archaeologists have interpreted them, and why the Galloway Hoard is truly unique.

What is a hoard?

A hoard can be many things. Often it is multiple objects of the same type or the same material, and usually precious metals.

Hoards are usually thought of as buried collections of precious objects. They may have been hidden for safekeeping, then lost or forgotten due to death or misfortune. Viking-age hoards are particularly susceptible to this stereotype. The period is so often seen as endless raiding, looting, warfare, and violence. There were many reasons for hoarding in the past, and many reasons why hoards might be preserved under the ground until the present day.

Interpreting Viking-Age hoards

The interpretation of Viking-age hoards is often based on ideas of hiding wealth with the intention of later retrieval. But the Norse sagas contain examples where wealth was buried in the ground deliberately so that it could be accessed in the afterlife. Treasures were also buried to seal an oath, or to claim land.

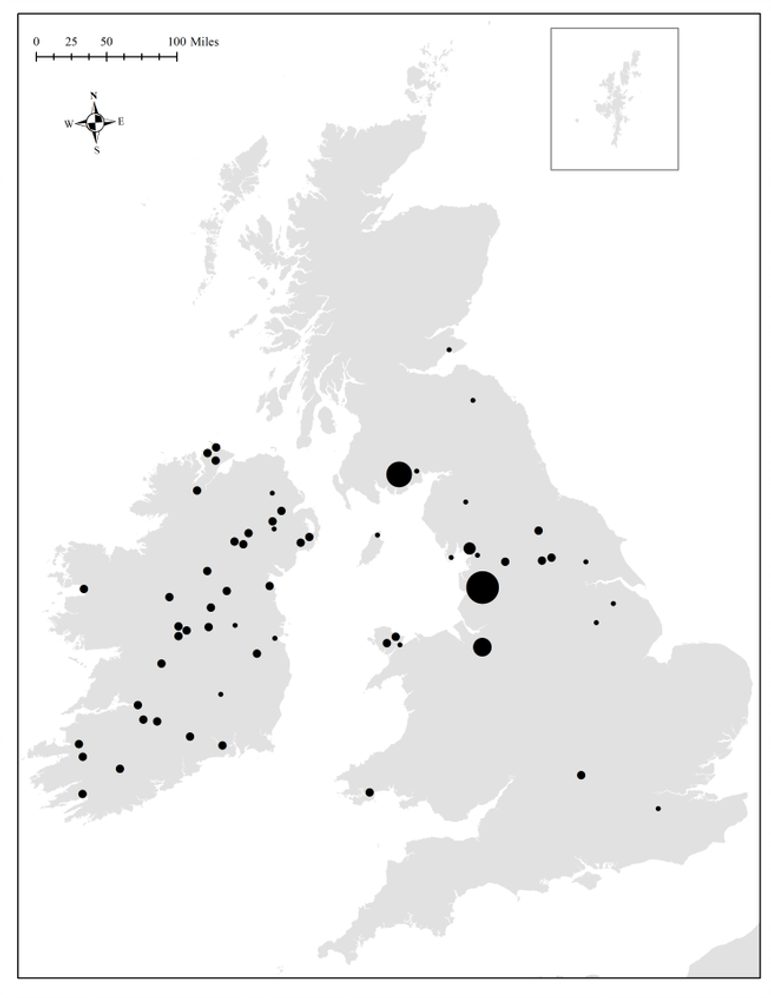

Many Viking-age hoards from Ireland are found in or near churches. These observations call into question our stereotypes about ‘Viking’ hoards. It makes us question who owned them and buried them, and the role of the Church in the silver economy in Viking-age Britain and Ireland. Even in a Christian context, sanctuary could be sought at a religious centre for possessions, not just people. Vows could be exchanged and arrangements made regarding retrieval, donation, and inheritance.

Understandings of hoards as either ‘economic’ or ‘ritual’ are reflective of modern, rather than contemporaneous perspectives. There was likely very little separation between spiritual and worldly value to the medieval mind.

The Viking Age in historical context

During the 9th century connections had been established across the North Sea to Scandinavia. This was through warfare first and settlement later. The first impact on Scotland was probably in the Northern and Western Isles. The earliest records are the fateful attacks on the monasteries at Lindisfarne (AD793) and Iona (AD795).

Chronicles and historical records were kept at these monasteries. The source material is probably accurate, but not unbiased. These primary accounts of predatory attacks on ecclesiastical sites by savage heathens have permanently affected the public perception of this period. This is a stereotype difficult to get away from.

We often imagine ‘Vikings’ as a new people, but they were not of a single geographical origin other than broadly Scandinavian. They integrated very quickly into the politics and society of Britain and Ireland. But they still maintained contact with their home territories. The case of the Gall-Gàedil (Gaelic speaking foreigners) whose name survives in the region of ‘Galloway’ shows that existing languages, habits, and customs were adopted by these newcomers.

Importantly, the Galloway Hoard is described as a 'Viking-age hoard', not a 'Viking hoard'. Through the 20th century the term 'Viking' has been misused. It often describes an ethnic identity for these Scandinavian colonisers, as if they were a single people or a nation. This is a retrospective view that does not match the archaeological evidence. People at the time did not know they were living through a Viking Age. Going ‘a-viking’ was an activity or way of life. They used several names for Norse-speakers like Northmen, heathens, Gaill (foreigners), but almost never Vikings!

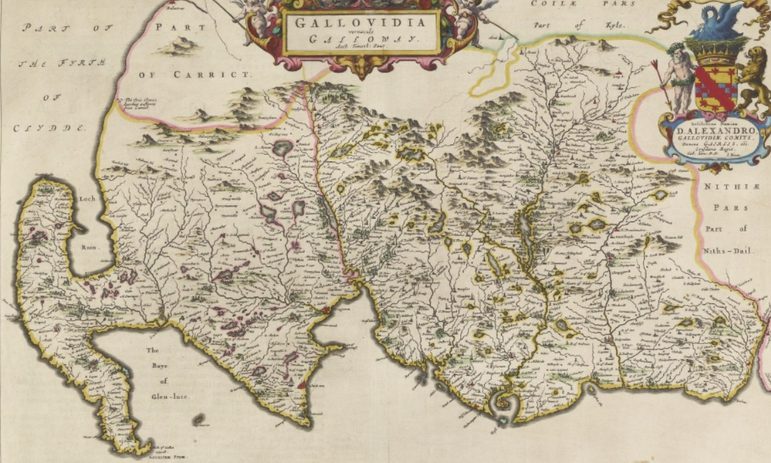

Galloway: a crossroads of nations

Historical sources are largely silent for Galloway. Formative events nearby, however, are well documented. The Great Heathen Army arrived in England in AD865, probably from a bay in Frisia at the mouth of the River Scheldt. In 876 the army took York. Their winter camps in Lincolnshire are associated with the prototypes of the types of arm-ring found in the Galloway Hoard.

In AD878 an Anglo-Scandinavian kingdom of York was established under a Danish Prince, Gudfrid. The prince had converted to Christianity and had the support of the Church of Saint Cuthbert. Ireland and Pictland were frequently plundered. A thousand captives were taken from Armagh in AD869, and Dumbarton Rock was besieged and destroyed in AD870 with two hundred ships returning to Dublin laden with captives.

During the second half of the 9th century, dynasties of Scandinavian origin controlled territories on either side of the Irish Sea. They had urban trading centres in Dublin and York. To the north, the Pictish kingdoms lost territory to Norse-speaking settlers, leading to the formation of the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba. The kingdom would later become the medieval kingdom of Scotland, and was first mentioned around AD900.

To the south, England was partitioned into an area of Danish rule (the so-called Danelaw). Alfred of Wessex and his descendants worked to unite the remaining realms into what would become England.

Between these emerging kingdoms was a more politically ambiguous area that has few surviving historical sources. From Chester to Glasgow there were Brittonic-speaking communities of the west. Areas like Galloway were subject to the fluctuating power of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. Galloway was also connected through its long coastline to the Irish Sea. It has considerable evidence for Viking-age hoards and finds. It even has a small number of ‘pagan’ burials with grave goods.

This is a pivotal time when the modern nations that now make up the United Kingdom are first appearing. But this is a retrospective view – the privilege of the historian. People at the time would have lived with fear and uncertainty. The danger of invasion, violence, and the threat of slavery brought by the changing social and political forces loomed. Yet, some also stood to benefit from these changes, creating new opportunities and forging new identities.

Galloway seems to have stood between worlds longer than most parts of Scotland. In the eleventh century there was a ‘king of the Rinns’. As late as the twelfth century the ‘earls’ of Galloway resisted the expansion of the kingdom of Scotland.

Galloway Hoard vs other Viking-age hoards

The Viking Age can also be thought of as a Silver Age. At this time new sources of silver became available through connections to Scandinavia, the Baltic Sea, and beyond. This abundance of silver is demonstrated through the increase in burial of silver hoards.

The main sources of Viking-Age silver in Britain were coinage from the Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian kingdoms. Dirhams from the Islamic Caliphates of Central Asia were also a key source.

A large proportion of the silver in the Galloway Hoard is incomplete. It contains hacked-up objects (hacksilver), as is common in Viking-age hoards. When items in a hoard are broken it is a sign that these fragments were valued for their raw material. They were being gathered for recycling, to be melted down and made into new objects. The ‘broad-band’ arm-rings found amongst the simple silver bars (ingots) are typical of the Viking-age Irish Sea zone. They are found in hoards dated to a short window of time, c 880-930.

Curating treasures, then and now

The Galloway Hoard also has old, worn, and fragmentary objects. Their material would not be suitable for recycling. They were kept, and in many instances carefully wrapped in silk, linen and leather, and buried within a special container. This immediately challenges some common modern assumptions. The value and the motivation for collecting and burying is called into question.

Anglo-Saxon metalwork and other unusual objects of glass, rock crystal, and other stones are not normally found in ‘Viking’ hoards. They do not fit traditional concepts of Viking-age wealth. A string of well-worn glass beads looks like it may have been used for decades if not longer.

Two remarkable pendants each contain much older material. A rock-crystal ball was maybe centuries old by the time it was mounted in silver. A unique pendant made from a broken glass bead, held together by its silver frame, was set with a pierced coin of Coenwulf, king of Mercia (died 821).

Initial radiocarbon dating of fragments of wool wrapping a silver vessel returned a date of AD 670-780. This pre-dates the first viking raid at Lindisfarne in 793. There are objects in the vessel also wrapped in silk or leather pouches which were treated with some care themselves. We know that sacred objects like relics of the saints were wrapped in silk in the early medieval period. It is possible the vessel contains objects venerated by their association with a saint’s shrine.

The Galloway ‘Hoard’ is therefore more than a single thing. There are hoards within hoards. Different parcels of silver may relate to the different names inscribed on the silver arm-rings. The vast array of materials – especially precious organic material – are only rarely found in hoards of this period. This poses new questions that may change what we think about the Viking Age.

Over a hundred objects brought together over several centuries can tell us about hundreds of ancient lives from over a thousand years ago. Men and women, makers and owners, traders and thieves, the pious and the profane – we may never know all their stories. But through further analysis we will know so much more about their world than we did before the Galloway Hoard was discovered.

There is much still to be revealed, and we know enough now to expect the unexpected.