Investigating the Galloway Hoard rock crystal jar

News Story

Some of the Galloway Hoard's most precious treasures were found packed in a silver-gilt lidded vessel. One of them was a unique object made of rare rock crystal fitted with gold. It has a fascinating history as well as an intriguing name on it.

Buried around AD900, the Galloway Hoard is the richest collection of rare and unique Viking-age objects ever found in Britain or Ireland.

The rock crystal object is one of several objects wrapped in textile from the lower deposit of the Hoard. These are the subject of a major conservation and research programme.

One of the wrapped bundles in the lidded vessel contained an object of rock crystal and gold. The wrapping itself was sumptuous. The object was first wrapped in linen, and placed in a pouch of fine leather, or suede. In between was a layer of samite, a luxurious decorated silk which must have come from Byzantium or Asia. The silk was precious in its own right, and appears to have been an inner lining for the pouch.

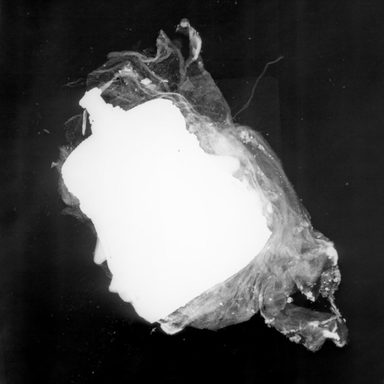

When the wrapped bundle was removed it was carefully recorded by AOC Archaeology using X-radiography. These were the first glimpses of the mysterious object underneath its wrappings. We saw a carved rock crystal, mounted with an elaborate gold meshwork with what appeared to be a spout at the top.

We worked in partnership with Dan O'Flynn in the Department of Scientific Research at the British Museum. Together we conducted 3D X-radiography that allowed us to see inside the wrapped bundle without disturbing the fragile textiles. Over 1000 X-ray scans were taken from every possible angle. These were then stitched together to produce a three-dimensional digital model of the object within. This allowed us to examine the rock crystal object and its gold meshwork for the first time. This method allowed us to preserve the integrity of the fragile fabric wrapping. Better informed, we could then plan further work.

The 3D digital model confirmed that the rock crystal was drilled through the centre and aligned with the spout on top. It was definitely a small jar. There was also a tantalising glimpse of an inscription in gold on the base. At that point it was still hidden by the wrapping. We then turned to the carved rock crystal, already visible in profile through its wrappings. The unique shape of the carved rock crystal also revealed a much longer history.

An ancient heirloom

Carved rock crystal is exceedingly rare in early medieval Britain and Ireland. Crystal of great clarity was difficult to find. The material is very hard and the expertise needed to carve rock crystal was not common in the ancient world. The workshops of Imperial Rome had the technology, but there was a lull until the later 10th century. This was when centres of production re-emerged in the Islamic Caliphate.

However, the Galloway Hoard was buried in the century before the rock crystal boom in Fatimid Egypt. The ends of the protruding lobes carved all around the surface are well worn. With a material as hard as rock crystal it would take a long time or a lot of wear to abrade away these leaf-like protrusions. This suggests that the origins of this carved rock crystal are likely to be much earlier.

The leaf-like protrusions around the carved surface of the rock crystal make most sense when viewed upside-down. They resemble acanthus leaves from the top of a Corinthian column, a common form of Classical architecture. Wherever the surface is unworn we can see additional details carved into the crystal, like leaf stems. Upside down, we can also see how the round top of the jar would have originally connected to a column below.

One of the uses of carved rock crystal in the Roman Empire was for miniature, architecturally-inspired pieces. Rock crystal columns very similar in size to the Galloway Hoard object survive in the Vatican collections in Rome. One has been found in the early Christian catacomb of Domitilla. These small crystal columns come in a variety of forms. The Corinthian capital is unique to the Galloway Hoard rock crystal. But all of them have central drilled cavities. This was perhaps to hold the separate components of the column together.

The Galloway Hoard rock crystal seems to have been kept as a prized heirloom. At some point, several hundreds of years after its original manufacture, this column capital was turned upside down and repurposed as a gold-mounted jar with a spout aligned on the central drilled channel.

A precious relic

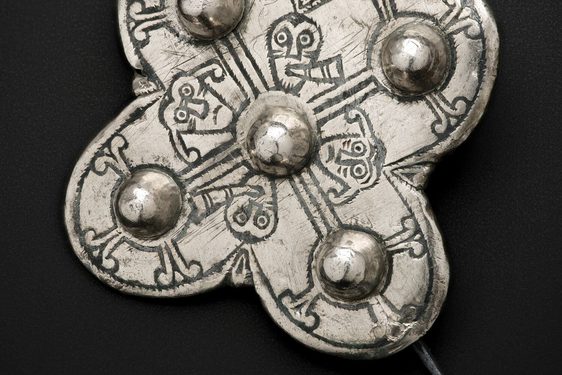

The goldwork on the jar is also unique. Numerous early medieval objects were decorated with filigree. This is a decorative technique using fine applied gold wire. This one stands out as especially complex.

Typically, Anglo-Saxon filigree makes use of beaded wire, which is absent here. Instead, the top of the vessel is decorated with spirals of twisted wire and granulation (small balls of gold individually soldered onto the object). A plaited wire binds the top to the meshwork that wraps around the carved surface of the rock crystal. The baseplate is also decorated in a similar, but again distinct, filigree technique. The exceptional quality of the goldwork indicates this piece was from a very high-status workshop.

The channel which had been drilled through the centre of the rock crystal when it was part of a column was aligned with the gold spout at the top. It was likely the jar was for holding a small amount of liquid. It is still not clear whether the gold base made the jar water-tight. The translucent nature of the rock crystal also makes it possible that it could have contained a solid object. Whatever it held, it would have been a precious substance. Lavishly wrapped, the jar and its contents appear to have been treated like sacred relics.

The biggest surprise from the 3D X-radiography was that the gold baseplate appeared to have an inscribed message. Its letters were difficult to read at first. They were made from a similar kind of gold wire and gold granulation that was used for the ornament on the top of the jar. Upon closer examination, and now free of their textile wrapping, the message reads:

+ H Y G V A L D E P : F A C : I U S S

+ Bishop Hyguald ordered [this] to be made

(Reading confirmed by Elisabeth Okasha, University College Cork)

The identity of Bishop Hyguald is subject to ongoing research. There is no documented bishop by that name. Other Hygualds are recorded in early medieval Northumbria, the kingdom which included modern-day Galloway.

The Durham Liber Vitae is a list of people associated with the monastic community of St Cuthbert. It has several instances of the name, but none are identified as bishops. However, there are interruptions to the historical source material from the ninth century onward. Hyguald is likely to be an otherwise unrecorded Northumbrian bishop from that time.

An ongoing investigation

Further analysis of the object may yet reveal more clues about where and when it was made, and what it was made for. But there are a few things that are already clear. Like the silver arm-rings inscribed with Anglo-Saxon runes, a pendant made with an early 9th century Mercian coin, and the name of a Northumbrian bishop on this object ties the Galloway Hoard ever more into the Anglo-Saxon world. It is easy to forget that much of what is now in southern Scotland had been part of the Northumbrian kingdom for over two centuries by the time the Hoard was deposited.

Along with the pectoral cross found in the upper layer of the Hoard, it is clear that some of the objects were property of the Christian Church at one point. The careful wrapping of the rock crystal jar is a glimpse at how precious relics, as this may have been, were kept and transported in this time. It is also a testament to the wealth of the Church in what would become Galloway, even at the height of the Viking Age.