The story of Jamaican silver during the colonial period

News Story

Content notification: this article includes a quote from an 18th century document which contains offensive language.

A large and important collection of silver objects made in eighteenth century Jamaica, when it was subject to British colonial rule, was generously bequeathed to the National Collection by Robert Barker in 2021.

The collection is made up of 57 individual items. Almost all were made in Jamaica. At the time of this silverware’s production, the economy of these Caribbean islands was built on enslaved plantation labour.

Over 30 years, avid silver specialist and researcher Robert Barker built this collection. Robert was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1960 and began collecting as a boy. Initially he focused on coins, before expanding to historic and contemporary silverware. He was not simply a collector, but also a scholar.

His interest in archival research led him to the rediscovery of an Assay Office in Jamaica. Assay Offices quality checked and marked all gold and silverware. The existence of the Jamaican Assay Office founded in 1747 suggests that such items were being produced on the island. This knowledge had previously been lost.

The mark of quality, or assay punch, from the Jamaican office was that of an alligator’s head. Once Robert knew what to look for, he set out to locate and collect silverware which carried the mark. He investigated a group of Scottish silver previously thought to be from Old Aberdeen due to the marks on it. In 1986, he published the results of this research in an article titled ‘Jamaican Goldsmiths, Assayers and their Marks from 1665 to 1765’.

The article laid out the argument for the reclassification of this silver from Scottish to Jamaican-made. His findings were met with widespread approval amongst silver specialists. This led to museums, like National Museums Scotland, updating their collections information to reflect the discovery.

The Makers

The Scottish connection runs deeper than the historic confusion over the Old Aberdeen silver. The creation of Jamaica’s Assay Office was brought about by the petition of two Scottish goldsmiths, Charles Allan and William Duncan. The system that was adopted was akin to the one running in Edinburgh. Around half of the silver in the bequest was made by Scottish goldsmiths who had emigrated to Jamaica. These included William Duncan, Charles Allan, Archibald Campbell, and John Roxburgh. The most prolific maker amongst these was Charles Allan. He partnered with Archibald Campbell after he arrived around 1742.

Archibald and Charles already knew each other from their time in Edinburgh. Their families had been friendly. When Charles was orphaned around the age of 13 it was Archibald’s father, Colin Campbell, who took him in and gave him an apprenticeship. This may have been due to a more intimate family connection. Allan’s mother’s maiden name was also Campbell.

Alongside these Scots, there are nine other goldsmiths associated with this bequest. These include Abraham Kipp from New York, Newcastle-trained George Hetherington, and Louis Dupont from London.

Louis Dupont is responsible for the only object in the bequest that is not Jamaican; a sugar caster. It was made in Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and Dominican Republic). It is thought that Louis’s father was the goldsmith Pierre du Pont from Poiters, France, and that the family were Huguenots. In 1747, Dupont declared bankruptcy and it was around this time that he ventured to the Caribbean. The plantation economy, based on enslaved labour, offered great financial opportunities.

Image gallery

The silver

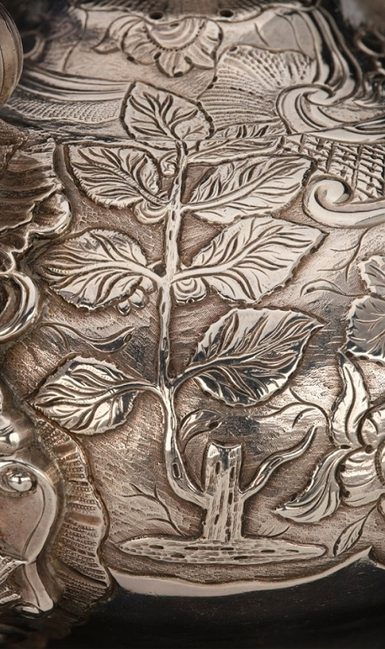

The group is an excellent representation of the types of silverware that you would expect to see during the eighteenth-century in wealthy households. It includes a tea kettle, a large two handled-cup, spoons and ladles, candlesticks and candle snuffers, sugar bowls, and salt cellars.

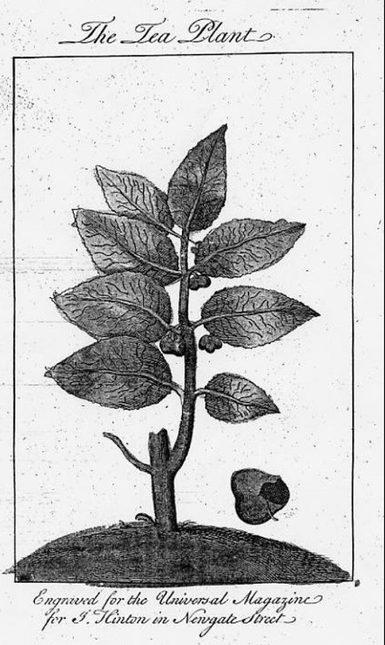

The tea kettle was made by Solomon Saldana and the plant decoration near the spout depicts a tea plant. His inspiration for this was located by Barker in the Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure. This was a periodical designed to be “instructive and entertaining to gentry, merchants, farmers, and tradesmen ...". It seems that the Magazine was important to goldsmiths too.

Slavery

Eighteenth century Jamaica was a centre of sugar manufacture. Its economy was based on the work of enslaved labour. The goldsmithing industry formed part of this colonial economy, and was therefore enabled by the profits of slavery. The silverware produced on the island was purchased by plantation owners. Some of the people who created it were originally enslaved.

Correspondence between Charles Allan and members of the Dalrymple family offers a glimpse into the world of an eighteenth century goldsmith in Jamaica. It reveals how this profitable business was fuelled by the labour of enslaved people. Allan borrowed a significant amount of money from Sir Hew Dalrymple, 2nd Baronet of North Berwick, and his brother Dr Robert Dalrymple. He used this money to help start his business in Jamaica. At one point, Allan struggled to repay the loans.

On 19 August 1746, Allan wrote to Sir Hew "I had at one time above ten white people who by there irregular life are all dead excepting one, their deaths was a prodigious loss to me". Later in the same letter, he wrote "my Negroes are all learning to work very well [and] I expect in six months' time to be able to do all my affairs without the assistance of white people".

Living on an island in the tropics proved difficult for many Scots. Not all of them liked or survived their time there. Yet people continued to emigrate to Jamaica during the eighteenth century. The majority emigrated to make money, which usually meant using an enslaved workforce. Allan’s letter highlights his own desire to use this labour to increase his profits. At the same time, he indicates that he is training enslaved people to work within the elite craft of goldsmithing.

Collections like this let us look deeper into the Jamaican manufacturing industry. We can unpick the international trading systems that brought such objects back to the ‘home country’. They tell of highly trained artisans, enslaved and free, working on the production of gold and silverware on the island of Jamaica. Today their legacy forms part of the largest collection of eighteenth century Jamaican silver in Britain in public ownership.

National Museums Scotland acknowledge gratefully the generous donation by Robert Barker of this fascinating and valuable collection.