The Culduthel wristguard rivet caps

This set of four small sheet gold caps that covered copper rivets on an archer’s stone wristguard.

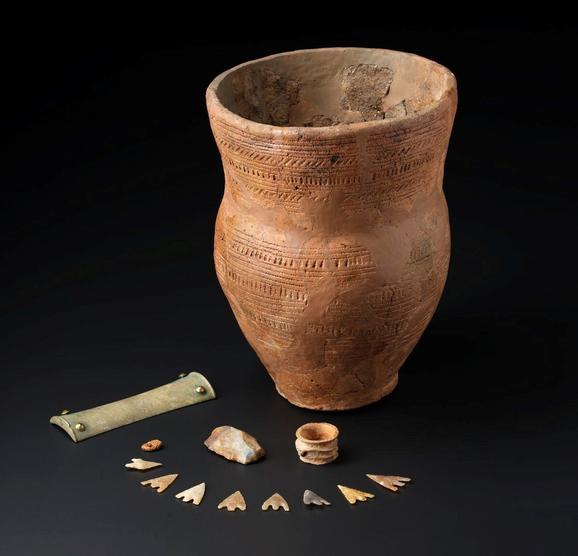

The wristguard was found in a stone cist (box-like grave) in 1975 in the grounds of Inverness Royal Academy, along with the remains of an adult man who had been buried in a sleeping position. He was accompanied by a large Beaker (which would have contained some kind of drink), a set of eight fine flint barbed-and-tanged arrowheads, a bone ring (possibly for a belt or for a quiver), an amber bead and a flint strike-a-light: everything that a high-ranking hunter/warrior would need for the Afterlife.

The bones have been radiocarbon-dated to 2280‒2020 BC, which means that this grave dates to either the end of the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) or the beginning of the Bronze Age.

Although the stone object has been called a wristguard (or bracer) – a device used in archery to prevent the bowstring from snapping back on the wrist – in fact it’s more likely to have been a decorative ornament that was riveted to the outside of a functioning wristguard made of animal hide. We can say this because a number of such objects have been found in graves on the outside of the forearm; the actual wristguard would serve its purpose on the inside of the arm.

The stone wristguard is very special.

Image gallery

It’s very rare indeed for a wristguard to have gold-capped rivets: only two others are known, one from Kelleythorpe, Driffield, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and the other from Barnack, Cambridgeshire. Both are in the British Museum.

The Kelleythorpe example is very similar in shape to the Culduthel wristguard, and all three of these gold-embellished wristguards have been made of tuff from Great Langdale in Cumbria. Thanks to research undertaken by Ann Woodward and colleagues, we now know that over a dozen wristguards were made from this rock.

So, the stone for the wristguard comes from over 300 miles (nearly 500 kilometres) away; and we don’t currently know where the gold originated, but it would certainly not have been local. This wristguard would have been an extremely prestigious possession, marking out its owner as a person of wealth and high social status.

And what’s even more fascinating is that isotopic analysis of the man’s tooth enamel has shown that he wasn’t a local. He most probably spent his childhood on the Antrim Plateau in north-east Ireland. So how did he come to be buried in Inverness?

We know that copper from Ireland was being transported to north-east Scotland at this time, probably via Kilmartin Glen and up Loch Ness. There are several other graves with Irish connections in and around Inverness, and so it may be that our well-dressed hunter/warrior had been an entrepreneur, involved in the importation of Irish copper. He would certainly have cut a dash with his fancy archery gear!

Dr Alison Sheridan, Research Associate on a.sheridan@nms.ac.uk