Old square toes: A rare pair of British jack boots

News Story

In 18th century Europe, developing trends in male footwear made sure that riding boots were – in Nancy Sinatra's words – 'Made for Walking'.

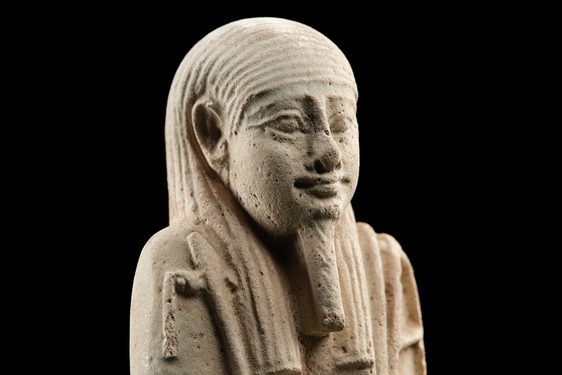

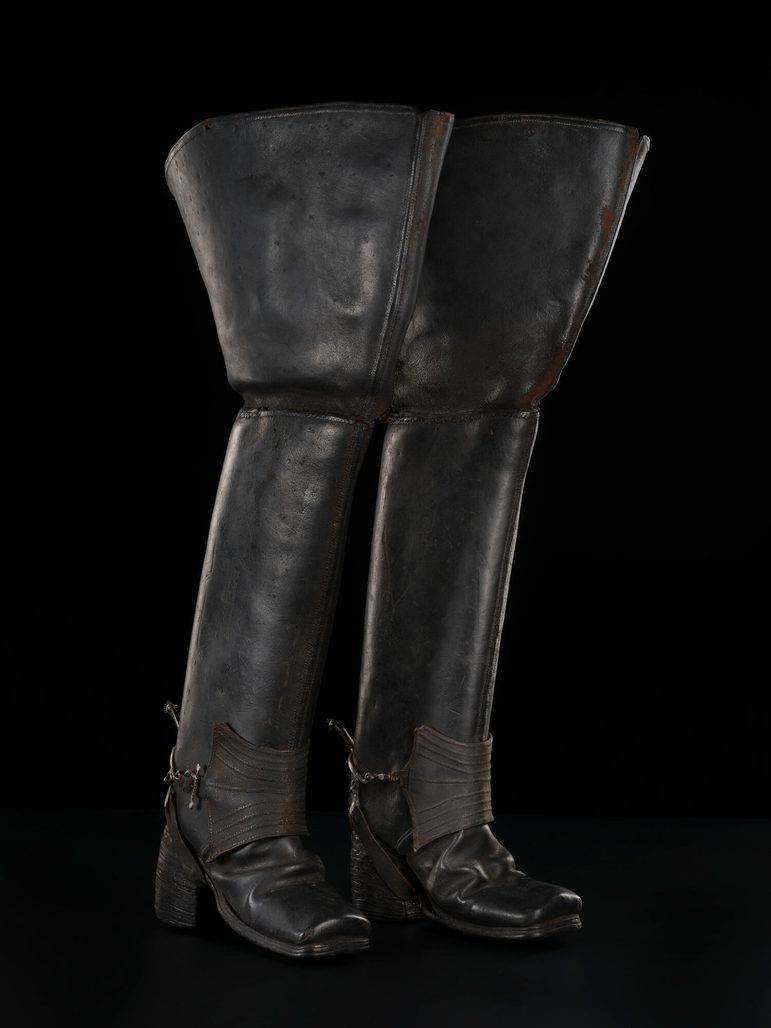

A pair of jack boots, cavalry boots or riding boots in black leather, c. 1660 - 1685. Museum reference V.2024.110.1.

Between 1720 and 1750, fashionable men were gradually casting off their equestrian jack boots in favour of jockey boots for greater mobility on foot.

Jack boots are incredibly thick, stiffened leather boots designed to protect and support a mounted rider. Jack boots of a different style are still worn today by the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment. Jockey boots are a much lighter, flexible leather with a stiffened sole. The flexible materials makes it easy for a rider to dismount then walk or run to their next venture.

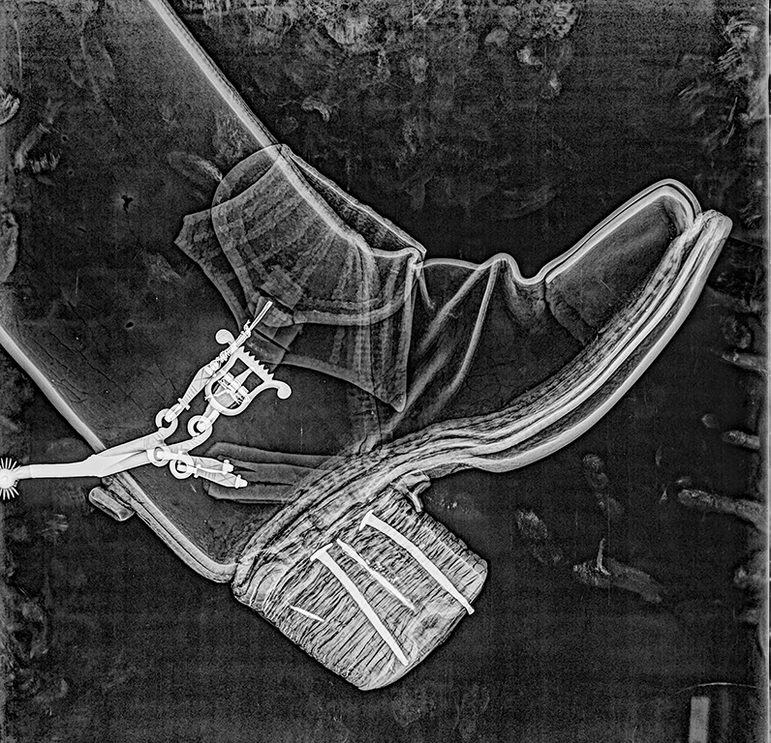

Detail of jack boot showing a metal spur with engraved detail and a broad leather straps across ankle front. Museum reference V.2024.110.1.

A pair of jack boots in National Museums Scotland’s collection likely date from the early 18th century. This was when jack boots began to fall out of popular use. The pair are currently the oldest non-archaeological men’s footwear in the collection.

For long-term preservation, they have been surface cleaned, assessed and photographed. The photography allows a greater number of people to see the boots, and reduces the need for handling.

To celebrate the boots’ newly revived looks and ongoing care, we delved into their cultural significance. The jack boots tell two stories. One is of the history of our collections; another is how they were used in day-to-day life during the first half of the 1700s.

Boots fit for riding

The jack boots were given to The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1838 by a Mr John Menzies. This collection is now part of National Museums Scotland’s holdings. They were described as a ‘pair of Jack Boots and Spurs, temp. Charles II’

They were understood as both an antique and a curiosity of dress, and likely to have been prioritised as very old and unusual boots. It’s not known that they had any specific connection to Scotland.

The reference to their era through a royal person is not coincidental. In 1838, painted portraiture was an important source for understanding the dress and armour of bygone eras. Worn when riding, jack boots were associated with the noble and regal patrons who commissioned equestrian portraits.

Styles of jack boots varied across Europe. Louis XIV was painted with his boots showing the distinctive red sole and heel he introduced to the French Royal Court.

Despite stylistic differences, they all fit the essential purpose of a thick, sturdy boot for horse riding. The sturdy construction of these boots made them a novelty, even when they were still commonly worn.

Portrait of a Man on Horseback by John Wootton, c. 1740.

Investigating the boots

When assessing the condition of the boots, our approach is to look for signs of their former life. A notable feature of these boots are holes in the upper leg leather, one of which has torn further. The holes serve no obvious practical purpose. Their position and no sign of attempted repair makes it probable the holes were created many decades ago: probably for display purposes in the 19th century.

Our preservation ethics today prioritise minimal intervention to objects. While unfortunate for their condition, the nail holes do tell us these boots were on show for an extended period.

Although not treated so reverently in the past, we at least know that the boots have been valued, viewed and enjoyed as part of our collections. The novelty of the jack boot is an enduring one.

Making jack boots

In his recent publication Shoes and the Georgian Man, Matthew McCormack explains how Jack boots got their name from the process of 'jacking', whereby hide was treated with wax and then tar or pitch to make it waterproof.

Our pair of boots have very heavily treated legs to make them completely solid, while the thigh covers have more flexibility. An X-ray revealed a double layer of leather over the toe. The heels and soles are created with layers of leather, pinned with nails.

During their years of use, the boots would have had regular and thorough applications of polish to maintain the leather. Our gentle surface clean has reduced the appearance of white residue that had begun to show on the boots, referred to by conservators as ‘fatty spew’. Fatty spew is essentially wax or other elements of the leather treatment coming out of the leather over time.

X-ray on jack boots which shows nails. Museum reference V.2024.110.1

Expensive footwear

Like many historic garments, 17th and 18th century jack boots rarely survive. But when they do they can tell us about past European cultures, and how British riding styles helped re-shape attitudes to formality in dress.

Boots were expensive in the 18th century due to the amount of leather used in their making. On average they cost five or six times that of a pair of shoes. Boots were a garment of wealthier classes, just as sport and cavalry riding were only afforded by specific classes. This means that in many cases their maintenance and care probably fell to a servant. However, jack boots were a good investment: they were so robust that their wear and tear would have been minimal. Lighter footwear required regular repairs. In the accounts of the Richardson of Pitfour family from Perthshire of around 1767–1780, new shoes and shoe repair bills were paid about every six months.

The robust and expensive nature of jack boots meant they were mainly (but not exclusively) associated with men in specific roles. In 1739 the Derby Mercury reported a highwayman thief wearing ‘a dark Drab Great Coat, dark Wig, and strong Jack Boots’.

In 1731 Walter Giles was convicted of stealing ‘Half-Jack Boots, one Great Coat, and one Silk Handkerchief, Value 25s. 6d.’ from a Hostler when he was resting at an Inn (Fog’s Weekly Journal, March).

A militant style

A series of toasts (oaths) listed in the Belfast News-Letter on 13 August 1779 and made by Lord Charlemont’s Company of Armagh Volunteers included: ‘Those that would rather die in jack boots than live in wooden clogs.’ It refers to the social distinction of making better wages while risking your life, or staying safe and poor.

A much earlier news item in 1719 stated the seizure of 300 pairs of jack boots as evidence of armaments intended for the Jacobite uprising. This makes it clear that jack boots were regarded as military and body armour (Flying Post, 17-19 March).

On our jack boots there is a carefully stitched repair in the thigh-protecting leather. Given the likely use of the boots as cavalry (or highwayman’s) equipment, this is potentially a repaired sword cut.

Detail of jack boots showing a stitched repair. Museum reference V.2024.110.1.

In 1733, Caledonian Mercury reported that the King of France had ordered his cavalry

‘to wear Jockey Boots instead of Jack Boots, that they may be the better in condition to serve on foot as well as on horseback’

Yet two years later papers were reporting the commissioning of thousands of jack boots in London for the Portuguese cavalry. The most practical decision for a military unit was evidently debated.

Jack boots in culture

In popular culture jack boots became a novelty or source of satire. In 1699 the Flying Post described a Sheriff in pursuit of a man escaped on route to being hanged:

‘not knowing what to do, gave his Horse and Jack Boots to a Fellow to hold and putting on the Fellows Brogues, he went about the fields [looking for his prisoner]’

Jack boots also featured in street performances. Artists used them for acrobatics, knowing that their audiences would understand the difficulty of wearing the boots.

The lack of mobility in jack boots leant itself to the popular British pastime of betting in the eighteenth century. In August 1750, one man won ‘a considerable Wager’ by walking ‘in French Jack Boots of 11 Pound Weight … from Shoreditch Church to the Three Mile Stone the Top of Stamford-hill’ in under an hour.

Close up of jack boots showing square toe. Museum reference V.2024.110.1.

Close up of jack boot showing stacked leather heel and square toe. Museum reference V.2024.110.1.

Fashionable boots

Riding boot design gradually trended towards a rounder toe and lighter fit over the course of the eighteenth century. As a result, the square toe and bulky stiff high leg of the jack boot came to be considered old fashioned.

In one printed exchange of October 1776, the correspondents were identified as ‘old square toes’ versus ‘young round toes’. Boot styles started to signify being old-fashioned versus modern and this cultural memory of jack boots out-lasted their use.

From the mid-18th century riders began adopting lighter jockey boot styles in Britain. This led to it being fashionable to be seen walking in town in riding dress, or when informally meeting friends. Turning up to social engagements in your riding boots would have raised eyebrows at the lack of formality, but it also signaled an active life and fashionable indifference. Pushing the boundaries of comfort and convenience between riding and socialising – casting off those jack boots – had a radical effect on deformalising elite dress codes.

Written by

Dr Emily Taylor

Assistant Curator, European Decorative Arts