The material lives of ordinary people: rare 19th century Chinese cotton

News Story

When you think of historical Chinese dress, what material comes to mind? Most people would probably assume silk. But the majority of the population in Qing dynasty China (1644-1911) actually wore cotton.

However, this reality is not reflected in museum collections. Chinese textile collections are dominated by silk clothing, often worn by the elite. This is because these fabrics are the ones that have survived. There is a critical gap between material survival and historical experience. This is the gap between what people collected versus what people actually wore.

A group of objects in National Museums Scotland provides a rare means of redressing this gap. They show the fabrics worn and used by ordinary people living through the tumultuous last decades of the Qing dynasty.

Image gallery

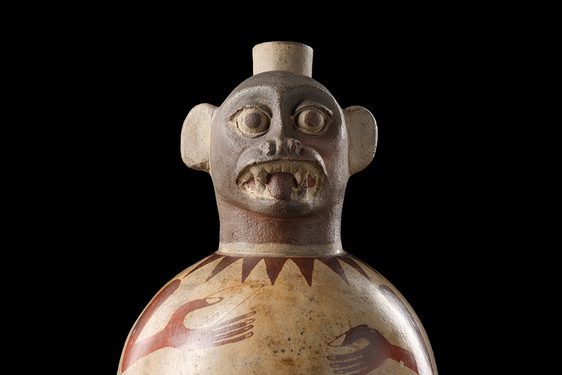

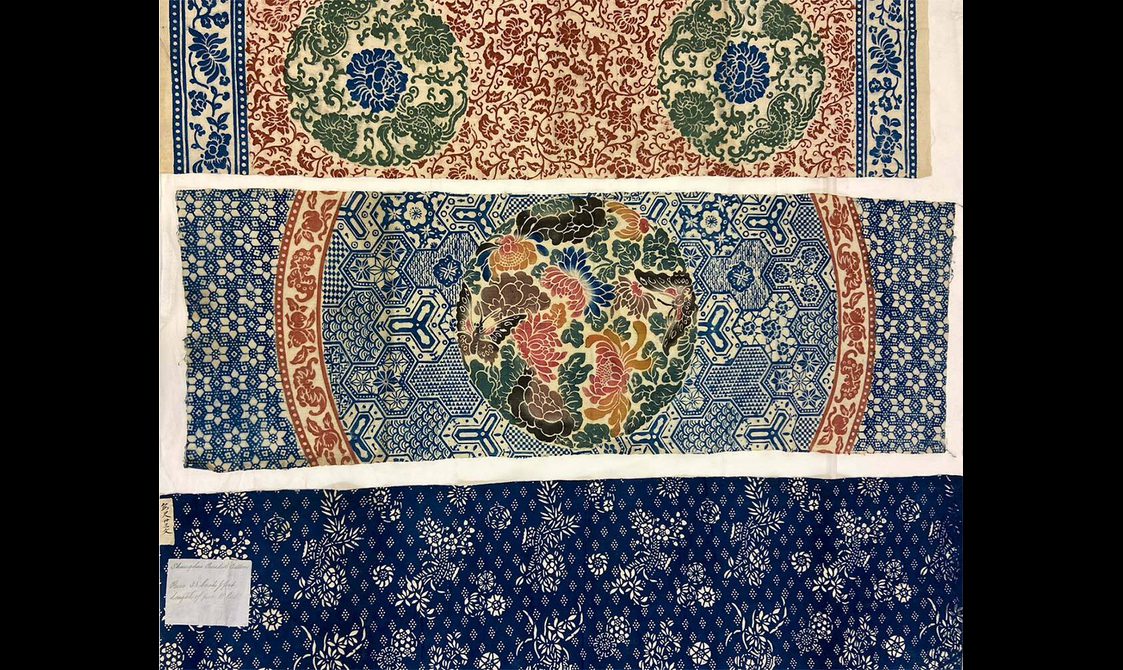

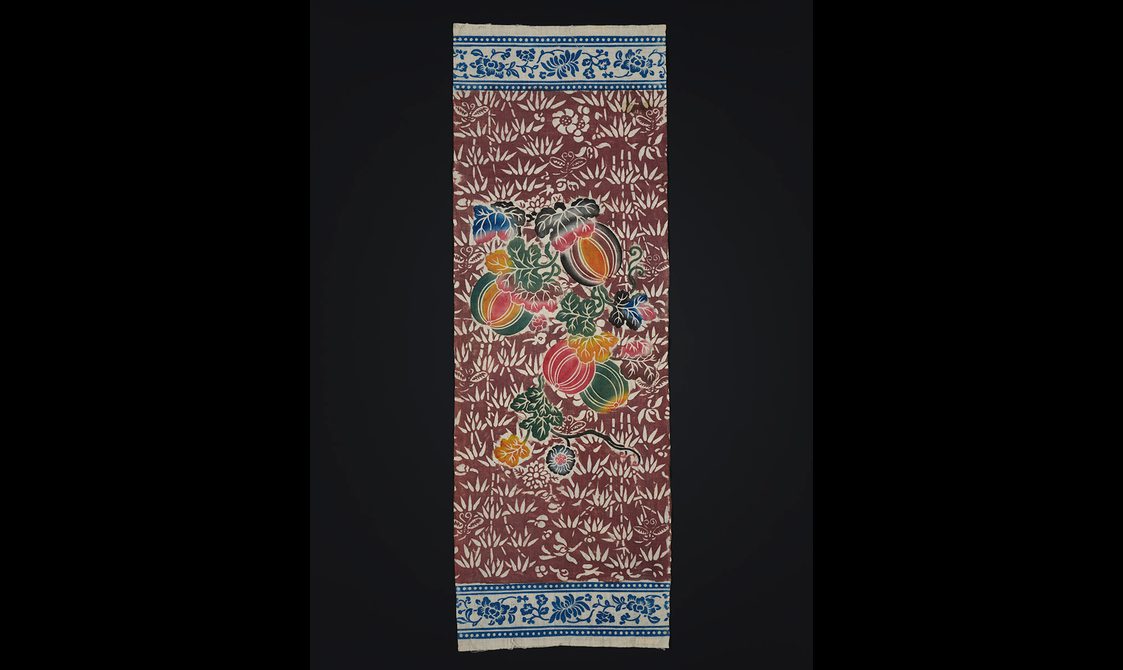

Three samples of printed cotton cloths, collected in Shanghai in the 1850s to illustrate the cotton manufacture in China. Museum reference A.129.D.1 series.

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.J

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.M

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.I

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.H

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.L

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.P

Colourful cotton designs

These plain-woven cotton fabrics are printed with bright colours. The designs are built around roundels of peonies and cicadas. Butterflies and flowers are set against a ground of geometric or floral patterns. These printed fabrics are samples, rather than complete pieces. Their designs suggest that three lengths were required to complete a piece, with the roundel positioned in the centre or in the four corners.

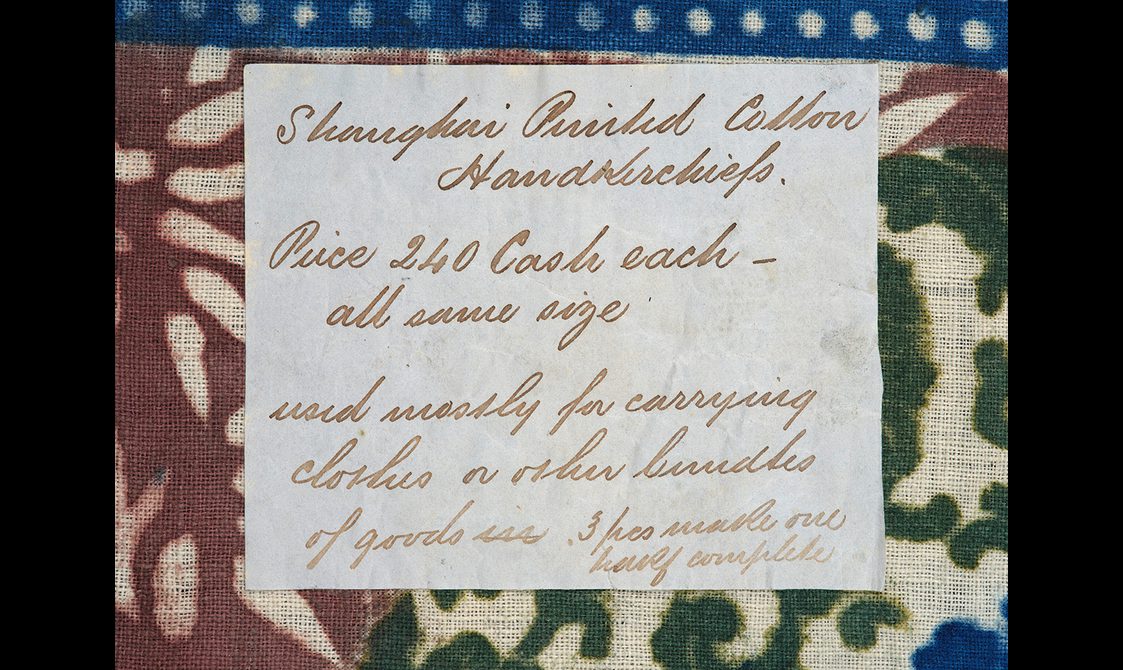

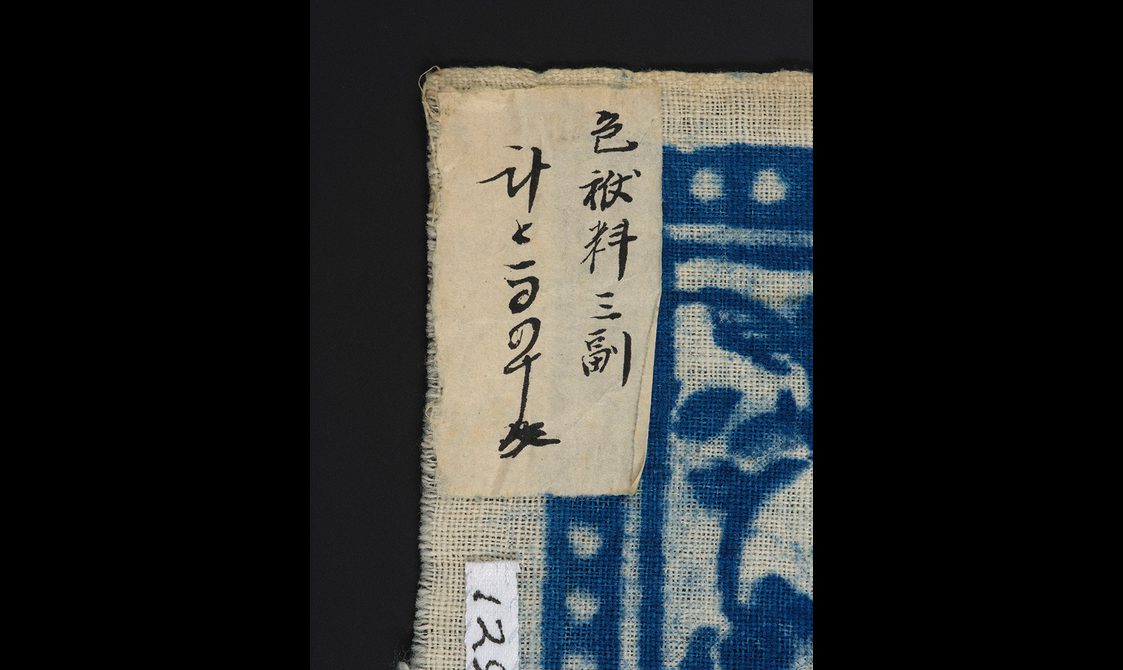

This is corroborated by Chinese and English labels on the back of two of the samples. The English label describes them as ‘Shanghai Printed Cotton Handkerchiefs,’ used for carrying clothes or other bundles of goods, but the Chinese label calls them a 'baofu' 包袱 or carrying cloth. They specify that three pieces made a complete cloth. The samples are priced at 240 'cash' or copper coins each. Since each sample measures around 35 x 100 cm, a complete handkerchief or cloth would have been around 100 x 100 cm or 1 square metre. These brightly coloured fabrics would have been a lot cheaper than silk versions.

These samples were likely collected to inspire Scottish textile manufacturers. The donor of the cottons was a merchant named Patrick J. Dudgeon (1817-1895). He first went to China in 1834, to Canton (Guangzhou 广州) where he worked for a company called Turner and Co. At that time, Canton was the only port in China that Europeans were allowed to trade from.

Image gallery

Handwritten label on printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.L

Handwritten label on printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.L

Printed cotton: China, Shanghai. Museum reference: A.129.D.1.L

British trade with China in the 1800s

The East India Company had successfully monopolised trade from China to Britain. They had been importing Chinese silks, porcelain, and tea from Canton to Britain since the 1700s. For many years they struggled to find a British trade good of comparable profitability to the Chinese manufactures. But by the early nineteenth century, imports of Indian raw cotton and opium allowed them to reverse the long-standing trade deficit.

In 1833, under pressure from northern industrialists and free trade campaigners, the East India Company’s monopoly was removed. Trade with China was now open to all. This was the year before Dudgeon arrived in Canton. He had made a fortune in his time in Canton. He returned home in 1850, before purchasing an estate in Kirkcudbrightshire in 1853.

Portrait of Patrick Dudgeon (1817–1895) by William Marshall Brown (1863–1936).

Collecting cottons for Scotland

Dudgeon's real passion was mineralogy. Educated at the Edinburgh Academy, he had founded the school's Mineralogical Society. He was no stranger to travel and had spent time collecting mineral specimens in China and Japan. He was likely commissioned to collect the cottons by George Wilson (1818-1859). Wilson had been appointed director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland in 1855 one year after it had been founded. The museum would later become the National Museum of Scotland.

With the goal of being ‘a Museum of the Industry of the world in special relation to Scotland,’ Wilson needed examples of industrial art, including those relating to textile manufacture. Or, what he described as: ‘all the intermediate bodies which intervene between such (finished) products and their raw materials’.

Dudgeon returned to China in 1857, this time heading not to Canton but to Shanghai, which was then in a tumultuous state. The British state had refused to bow to the Qing government’s desire to stop the import of opium. This had led to the first Opium War (1839-1842).

Overpowered by superior British military technology, China had to sign the Treaty of Nanjing (1842). This was one of a series of so-called 'unfair treaties' that it would be forced into signing over the coming decades. As a result, five other ports including Shanghai were opened to foreign trade.

New trade routes with Shanghai

Shanghai was sited near to Jiangnan, the leading regional producer of silks and cottons, and the economic heart of China. It became the most important port in China. There, Dudgeon collected a group of 71 objects. These were titled as: ‘Illustrations of the Chinese Cotton Manufacture and Models and Tools’.

Museum records tell us they contained everything that you would need to make Chinese cotton fabric in this period. The collection featured a basket used for picking cotton in the field as well as a spinning wheel and yarn traveller. There was a cloth loom complete with cloth partly made and a muster of new cotton roved ready to spin. There were also specimens of plain, dyed, and printed cloth.

But Wilson died in 1859 and seven years later, the Industrial Museum of Scotland redefined itself as the Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art. After its rebrand, the museum was more concerned with art and design than industry. These models of manufacture collected by Dudgeon became less relevant to its mission. Over the course of the early twentieth century, the museum deaccessioned most of the raw materials and tools. Only fourteen objects from Dudgeon’s collection remain.

However, the museum kept what are arguably the most important objects. The seven printed cotton lengths and the cotton printing woodblock still survive today. Together this group speaks to a cotton printing tradition that has been little explored in Chinese textile history.

Millions of bolts of Chinese cotton

It has been estimated that in the mid-nineteenth century, China produced around 600 million bolts of cotton per year. In comparison, 15-25 million bolts of silk were produced. Every year, about 300 million bolts were produced by families for their own consumption. The other 300 million bolts were produced for the market. The best quality cottons came from Jiangnan – the region around Shanghai. Its annual production has been estimated at 45 million bolts of cotton. The bulk of this would have entered long-distance trade within China, but it was also produced for export markets.

Each year about one million bolts of a plain-woven, undyed fabric were exported from Canton to Europe. These were called nankeens because they were believed to have been produced in Nanjing (Nanking). However, this is a misconception, as they were also produced elsewhere.

Image gallery

Pair of man's nankeen trousers of beige cotton with straps to go under the foot: British, about 1830 - 1840. Museum reference: A.1978.539

Pair of man's nankeen trousers of beige cotton with straps to go under the foot: British, about 1830 - 1840. Museum reference: A.1978.539

Pair of man's nankeen trousers of beige cotton with straps to go under the foot: British, about 1830 - 1840. Museum reference: A.1978.539

Pair of man's nankeen trousers of beige cotton with straps to go under the foot: British, about 1830 - 1840. Museum reference: A.1978.539

There are several examples of nankeen pantaloons in National Museums Scotland's textile collections. One pair from the 1840s shows why the material was so popular. The sturdy, tightly woven fabric was perfect for the new tailored trouser styles of the early nineteenth century. Much of what survives in museums is this undyed, plain-woven cotton produced for export. However, contemporary texts suggest that Jiangnan was also renowned for its brightly coloured and printed cottons that would have been sold in domestic markets.

Most stages of Chinese cotton fabric production were rural household activities done by women. A woodblock print genre known as the 'Ten Tasks of Women' shows a woman engaged in the tasks of making cotton fabric. She is shown ginning, bowing and spinning the raw cotton, sizing the warp, warping the loom, and weaving the cloth.

A scene depicting the different stages of cotton production. Fangzhi tu 纺织图, Fengxiang county, Shaanxi 凤翔县(陕西), Qing dynasty, woodblock print, after Zhongguo minjian nianhua shi tulu, shang 中国民间年画史图录, 上, p.161, no.160.

However, the finishing stages took place in large-scale urban workshops. Male wage labourers would be employed for calendaring, dyeing, and printing. Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these workshops expanded their range of dyes. One cotton merchant's manual listed 68 recipes for different colours. These shades included evocative names like ‘swallow tail blue’ or ‘eagle back grey’.

Cotton cloth printers also became renowned for their printing techniques. China has a long history of producing printed textiles. This includes the clamp-resist dyed silks of the Tang dynasty and the wax-resist batiks developed by Miao ethnic groups in Guizhou.

In the Jiangnan region, the most prevalent printing method was paste-resist blue and white prints. These are created by applying a resist paste made from lime powder, glue, and alum to a wooden stencil, and then submerging the cloth in a vat of indigo dye. This technique was known as 'medicine spot cloth' (Yao ban bu 药斑布). There has been a revival of this tradition today by contemporary artists. This style has been replicated by Wu Yuanxin 吴元新, founder of the Nantong Blue Calico Museum.

Contemporary artist Wu Yuanxin 吴元新 in his studio.

Evidence of a rare printing technique

The cottons in National Museums Scotland’s collection evidence a lesser-known printing technique. In the early nineteenth century, a Shanghai man named Chu Hua wrote a Cotton Manual (Mumian pu 木棉谱). This was a survey of the cotton industry, including printing and patterning. He mentioned one technique where wooden blocks were carved with motifs of flowers, birds, and animals. The cotton cloth was then placed on top of this block, and several colours were brushed on to create an effect he described as colorful as painting. This type, known as 'brush printed patterns' (shua yin hua 刷印花) is the technique shown in the examples collected by Dudgeon.

The wooden printing block in National Museums Scotland's collection is carved with designs on both sides. One side features carvings of scrolling naturalistic floral branches and birds. The other side of the block features a geometric pattern known as Song brocade (Songjin 松锦). The block is quite large, measuring 70 cm x 49 cm. It is too big to pick up and print from as you would an Indian cotton printing block, or indeed a Scottish one of this period.

The museum register, based on Dudgeon’s notes, records that:

‘The chintz is made by wetting the block with dye, by the short haired brush first, the cloth is then laid on and rubbed over the pattern, occasionally applying fresh dye over the cloth with the long brush.’

Image gallery

Chintz block with patterns carved on both sides: China, 19th century. Museum reference: A.129.C.1

Chintz block with patterns carved on both sides: China, 19th century. Museum reference: A.129.C.1

The lost art of printed cottons

But why do so few examples of this technique survive today? To answer this, we need to look to the Shanghai textile markets where Dudgeon purchased the cottons.

Chinese textile markets were reshaped by foreign cotton manufacture after trade routes opened up in the mid-nineteenth century. Alongside Chinese-made cottons, Shanghai markets now sold Indian chintzes as well as industrially produced cottons from Britain, America, and Russia.

In his publication ‘A Chinese Commercial Guide’ of 1848, John Robert Morrison described how foreign chintzes:

'should be well covered with large gay flowers, green ground preferred. No formal figures or Chinese representations are suitable. Swiss and French chintzes preferred to English.'

But the fifth edition of this work, published 15 years later, cautioned that these foreign cottons were consumed chiefly in the maritime provinces. It added that they formed just a small proportion relative to native manufacture throughout the empire.

'Chintzes and prints (yinhua bu 印花布) have been greatly overdone during the last few years; the China markets can only take off a very limited quantity.'

These vibrantly coloured cottons with their 'Chinese representations' of peony and cicada roundels demonstrate why imports of foreign cottons found a challenging market in China.

But a later account, a local gazetteer of Shanghai county (Shanghai xianzhi zhaji 同治上海县志札记) written in 1871 gives more context for these fabrics. It said that these brush-printed designs were used mainly for quilts and bundle wrappings, and not many people wore them as garments.

The technique fell out of use which makes it all the more remarkable that these objects survive. Not only do they represent Chinese cotton printing traditions, but also the colourful patterns bought by ordinary consumers.

Written by

Dr Rachel Silberstein

British Academy Visiting Fellow