Annie Pirie Quibell: An early female Egyptologist from Scotland

News Story

Aberdeen-born Annie Pirie was one of the first women in the United Kingdom to study Egyptology. Discover how this trained artist and archaeologist has left a lasting legacy.

Of all the different dwelling places, give me, for choice, if not too long a time, a good tomb.

Annie Pirie Quibell, A Wayfarer in Egypt

An artist and an Egyptologist

Annie Abernethie Pirie Quibell (1862 – 1927) was born in Aberdeen. She was the daughter of William Robinson Pirie, a Church of Scotland minister and Principal of the University of Aberdeen. She originally trained as an artist and exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy.

In the 1890s, she was amongst the first women to study Egyptology at University College London (UCL) with the celebrated archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie. Petrie’s position was funded by Amelia Edwards, the novelist, Egyptologist, and co-founder of the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society). Edwards chose UCL because it was the only university in the UK at the time that allowed women to be awarded degrees.

Egyptian excavations

Together with his wife Hilda, Petrie excavated important archaeological sites across Egypt. As part of his excavation team, he often took his students to learn how to excavate. In 1895, he invited Pirie to join his excavations as an artist. She went on to work at several key sites, including one of the earliest temples in Egypt, at Hierakonpolis.

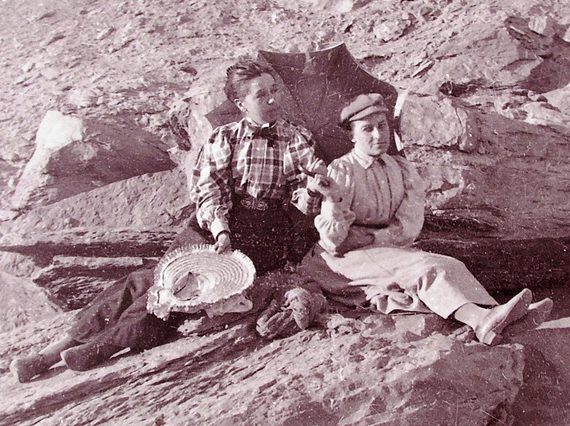

Annie Pirie (left, in plaid) with her future husband's sister Kate Quibell (right) at Hierakonpolis in 1898.

The City of the Falcon

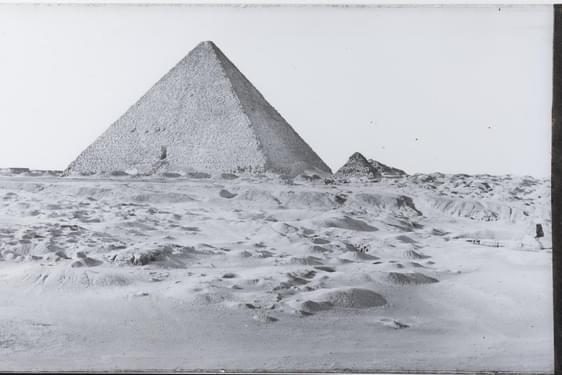

Hundreds of years before the pyramids were built, Hierakonpolis was one of the largest settlements on the Nile. Known to the ancient Egyptians as Nekhen, it was the site of a very early temple dedicated to the falcon-god Horus (c 3400 BC).

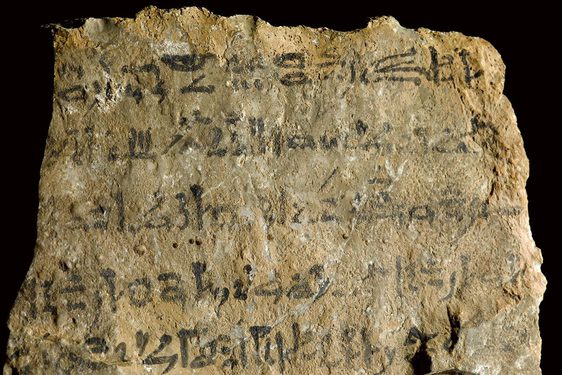

During excavations in 1897-98, a group of objects in stone, ivory and gold, were found buried in a deposit beneath the temple floor. They had been given as gifts to the god around 3000 BC and had been gathered and buried at a later date. These very early finds revealed the foundations of ancient Egyptian religion, kingship, writing and art; as many of these motifs set the standard for the next 3000 years.

Cast of one side of the Narmer palette. The original is made of siltstone and is decorated on both sides and was excavated at Hierakonpolis in 1895. Museum reference A.1974.104.

One particularly important object excavated at Hierakonpolis in 1895 is the Narmer palette. The original is made of siltstone and is decorated on both sides. The largest figure represents one of the first kings of a united Egypt, King Narmer. He is shown about to attack a fallen enemy with a mace.

Illustrating Egypt

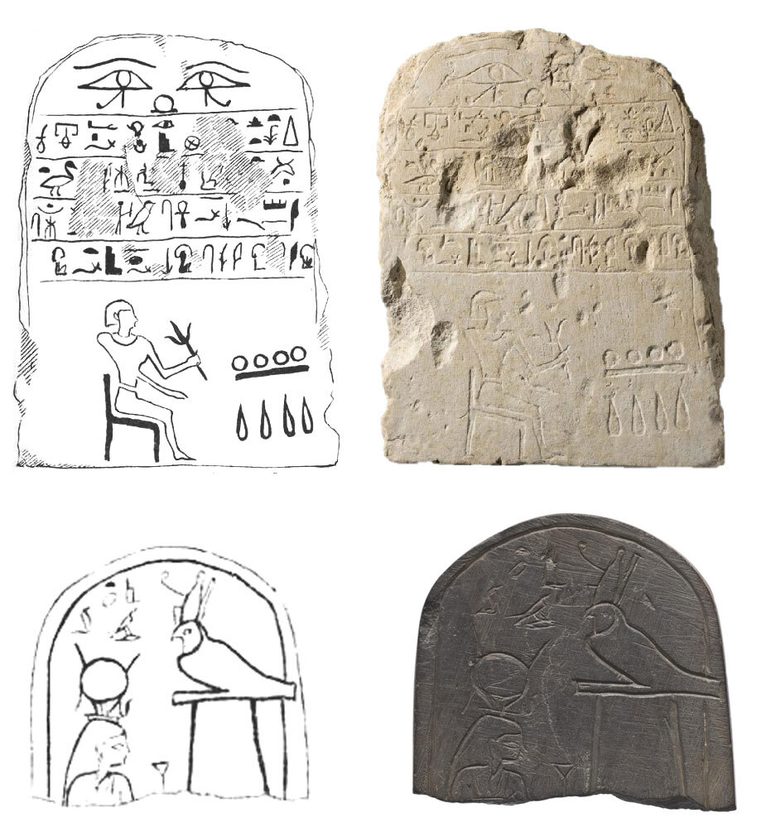

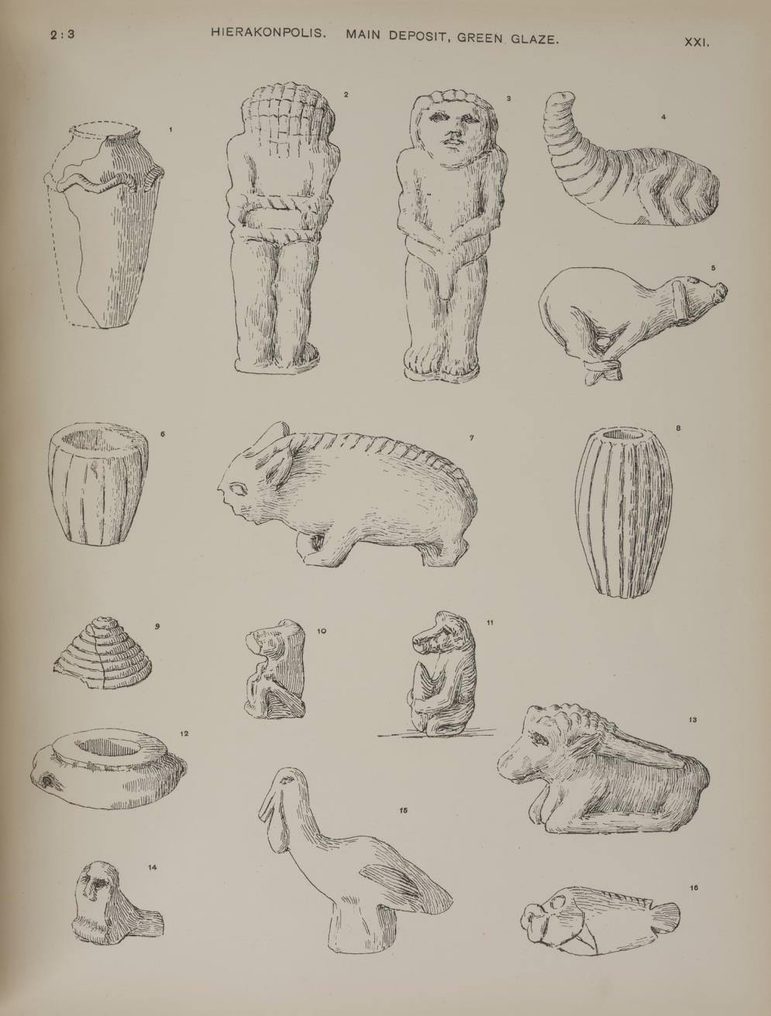

During her time working with Petrie, Pirie’s artistic skill was put to great use, illustrating these unique finds and sites. She produced many of the object illustrations for the excavation publications of the Egypt Exploration Fund (today Egypt Exploration Society). The Fund was founded in 1882 by the writer and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards, and it funded many of Petrie's expeditions. Pirie's illustrations include objects found at Hierakonpolis that are now in the National Museums Scotland collection.

Drawings made by Annie Pirie Quibell of stelae excavated at Hierakonpolis. Stela top right, museum reference A.1956.346. Stela bottom right, museum reference A.1956.344.

Love in the desert

During one of the excavations, Pirie and Egyptologist James Edward Quibell fell in love, apparently while they were both suffering from a bout of food poisoning (a frequent occurrence on Petrie's excavations!). They married in 1900 and worked together in Egypt until 1914, including eight years at the site of Saqqara.

Alongside her illustration work, Pirie wrote Egyptological publications for the general public. Working with her husband, she produced an English translation of the 'Guide to the Cairo Museum' in 1906. She also wrote short guides to Saqqara and the Giza Pyramids for military staff stationed in Egypt.

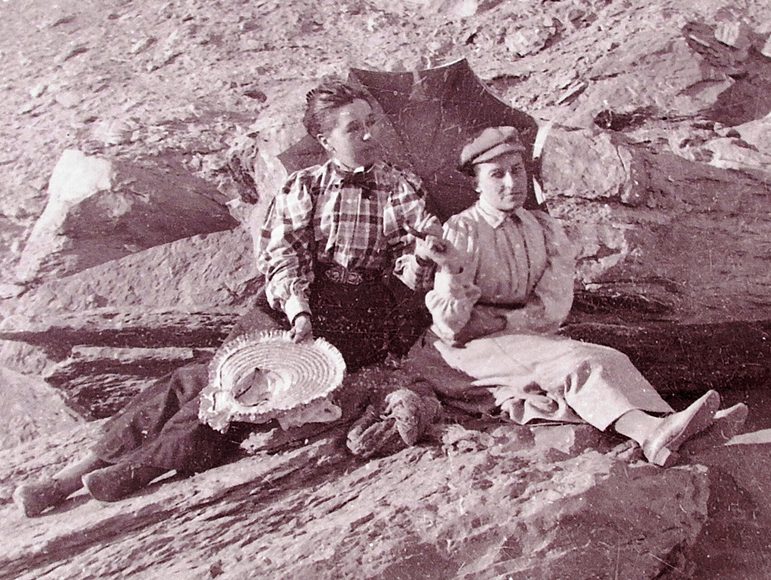

Annie Pirie and her husband James Quibell, January 28, 1902.

Return to Britain

After returning to Britain, Pirie published two further books, 'Egyptian History and Art' (1923), and a memoir 'A Wayfarer in Egypt' (1925). She was also responsible for arranging the Egyptian gallery at the Marischal Museum at the University of Aberdeen.

She died of leukaemia 1927 at the age of 65. She left a lasting legacy, particularly through her illustrations, which are still used by researchers today.

A book plate of a series of drawings by Annie Pirie Quibell of objects excavated at Hierakonpolis. From J. E. Quibell, Hierakonpolis Part I (1900). Museum reference LIB.2017.7.1.

You can see objects excavated and illustrated by Annie Pirie Quibell in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.