Coco Chocolatero: Feathered Serpent or Fire-Breathing Dragon?

News Story

This small, polished coconut shell harnessed into the form of a goblet is an example of a colonial American houseware that may be unique in Scotland.

Properly known as a Coco Chocolatero, this is a style of coconut cup developed in the Americas, specifically for drinking the important indigenous beverage, chocolate.

The Coco Chocolatero. Museum reference A.1956.1384.

Coconuts and chocolate

Coconuts, otherwise known as 'Indian nuts', had been a regular, and early import from South Asia into the Mediterranean area since the second century, along with other, better known commodities like pepper.

Coconuts were considered medicinal and magical, and created curiosity as exotic new things during the Age of Exploration. Coconut shells used as cups became commonplace and by 1500, the coconut cup was an established and popular form of European fine luxury dinnerware.

The Spanish and Portuguese brought coconuts and coconut cups with them when they arrived in the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century.

Chocolate was the indigenous formal beverage in the American regions where Europeans invaded first. It was very culturally significant: taxes were paid to the Mexican Empire in cacao beans, and chocolate consumed only by the highest castes. Europeans very quickly adopted this drink.

Cocos Chocolateros

The term 'Coco Chocolatero', or 'Coco' for short, appears in colonial American language by the late 16th century. These coconut cups were designed specifically for drinking chocolate, as opposed to wine, or other drinks, of their European counterparts.

Medieval and early modern European coconut cups consisted of large coconut shells and generally stood on tall, handle-less stems. Colonial Latin America heavily influenced fine European dinnerware trends resulting in new Coco Chocolatero designs. European coconut cup stems were shortened, the shells shrank substantially, and the cups sprouted small handles.

The American coconut cups metalwork was cast using moulds, which were copied and shared, so similar shapes appeared over and over again. Handles much like the museum’s Cococan be found elsewhere, and another popular handle featured the Spanish lion.

An example of a coco cup in our collections. This coconut cup with silver mounts is possibly late 16th century. Museum reference A.1960.762.

Popularity

Cocos made their way back across the Atlantic as the popularity of chocolate spread, along with other types of chocolate-drinking accessories such as silver spoons and silk handkerchiefs.

According to descriptions in inventories and newspapers, by the seventeenth century, even English royalty owned Cocos Chocolateros.

The Earl of Sandwich’s 1668 hot chocolate recipe for two - as featured in Tatler Magazine in December 2021 - calls for:

4 tbsp raw cacao

1 tsp cinnamon

Pinch of Jamaica pepper (allspice)

2 tbsp sugar

3 vanilla pods, removed before serving (or 1tsp vanilla essence)

Milk – to drinkers’ taste

By the eighteenth century, cocos were so well-known that Mexican painter Antonio Pérez de Aguilar included one in his still life of a cupboard.

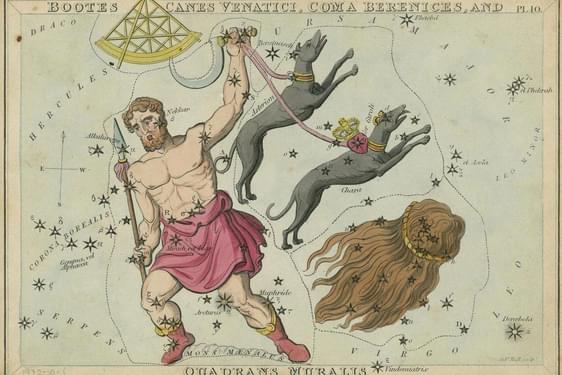

Antonio Pérez de Aguilar’s Alacena (Cupboard), oil on canvas c.1769. The Coco Chocolaterois at bottom centre. Antonio Pérez de Aguilar. Museo Nacional de Arte

Snakes or dragons?

On our Coco, the snakes may suggest an origin in present-day Mexico or Guatemala. The snakes possibly represent the feathered snake god of the Mexica and Maya, Quetzalcoatl, who was often depicted with a head and looked dragon-like to Europeans.

Snakes, dragons, or Quetzalcoatl? Detail of the silver stem of the Coco Chocolatero. Museum reference A.1956.1384.

This very American Coco Chocolatero may also reflect a Spanish-American silversmith’s impression of Chinese dragons. Colonial Spanish-American elites were just as familiar with Chinese porcelain as their European peers, and some may even have appreciated the similarity of Chinese dragons with Quetzalcoatl. During the the Spanish empire, Chinese goods, including porcelain decorated with dragons, were loaded onto Spanish ships in the Spanish Philippines, carried across the Pacific, offloaded in western ports, carried overland to eastern ports, and then shipped across the Atlantic to Spain.

Detail of the Coco Chocolatero’s silver handle. Museum reference A.1956.1384.

Journey to the museum

We are yet to find the specific origins of the Coco Chocolatero or of its counterpart, which was gifted to National Museums Scotland on behalf of Sir Eric Miller (1882-1958) in 1956. It is one of a number of silverware items which were gifted and acquired by National Museums Scotland with the aid of The National Art Collections Fund from Sir Eric Miller.

The ‘counterpart’ to the coconut cup. English, London, 1653 – 1654 (Museum reference A.1955.233.

Miller became an avid collector of antiquities, arts and books from British dealers and auctions and a valued contributor to museum and library collections. Born Hans Eric Müller, Miller was from Darlington in north east England, the son of a German schoolmaster. After his father’s death he moved to London and had a long business career with the company Harrisons and Crosfield.

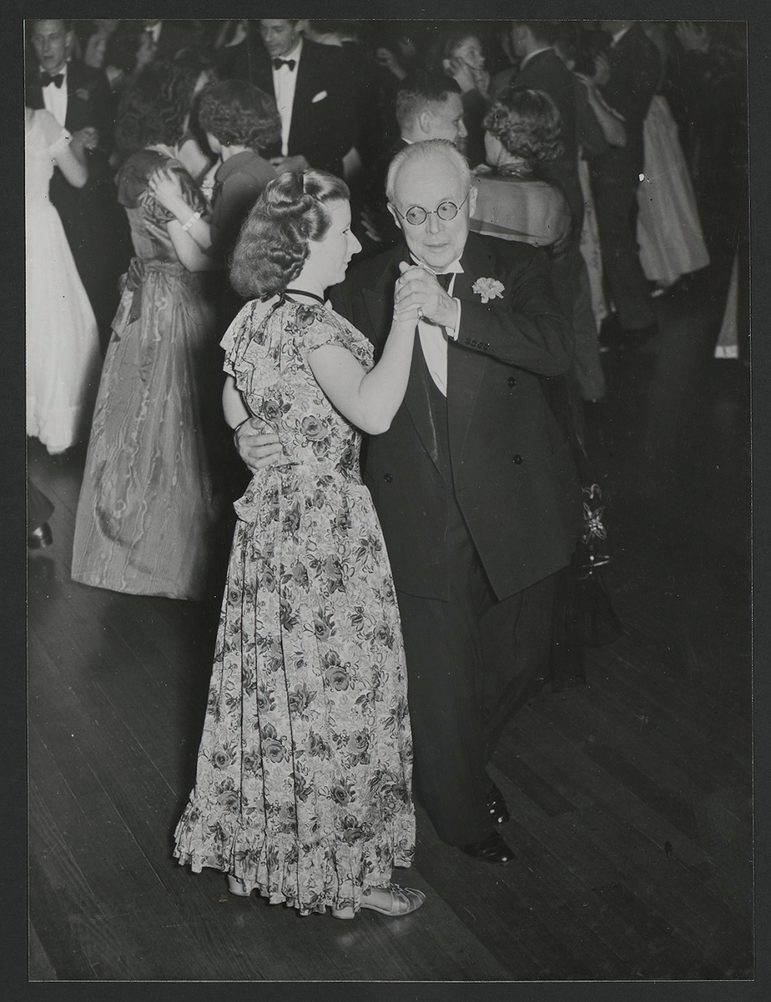

Image featuring Sir Eric Miller (director 1908-58, chairman 1924-56) at a reception celebrating his 50 years with Harrisons and Crossfield.

Harrisons and Crosfield originated as a Liverpool firm, then traded from London after 1854. It was parent firm to many international companies and Miller held directorships of eighteen of them during his career. One of their core interests was the rubber trade, which Miller was at the heart of: he was secretary to the first rubber plantation company to be floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1903. Miller had business colleagues in Edinburgh (home of North British Rubber Company from 1894) and perhaps visited the Museum one of his business trips to the city.

Miller had a personal decorative arts collection and during his lifetime he contributed both directly and indirectly to many other public collections including: The National Maritime Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Port of London Authority Library, the British Library, the British Museum, the library at Malay House and the new Malayan Museum, both in colonial Malaysia.

Coffee and independence

As independence movements spread across Latin American in the nineteenth century, Cocos Chocolateros came to be seen as mementos of a colonial past and they gradually fell out of use. This was about the same time that coffee replaced chocolate as a preferred beverage and as an important cash crop for new nations.

Our cup is likely to be an example of colonial nostalgia rather than dating to the colonial period. Until more scholarly work on Cocos Chocolateros occurs, and without scientific assessment of the metal content of our Coco, its route to Scotland from the Americas remains a bit of a mystery.

With thanks to Professor Kathleen Kennedy for contributing to this article.