A medieval masterpiece: The Monymusk reliquary

News Story

The Monymusk reliquary is arguably the most important piece of early Christian metalwork to survive in Scotland. It is also one of the most iconic objects in National Museums Scotland’s archaeology collections.

Discover how this fascinating object was constructed, and what it tells us about early medieval Scotland.

What is a reliquary?

Reliquaries were used to keep holy remains secure and control who could access them.

The portable nature of the reliquary allowed it to be carried and transported with ease. The Monymusk reliquary was empty when acquired by the Museum. There are no surviving records of the original contents. It is a small box, so could only have accommodated little objects such as small corporeal (body) relics, stones, or pieces of cloth. Alternatively, it may have contained other holy substances, such as oil for anointing.

The enameled side plate, originally one of a pair, enabled the Monymusk reliquary to be carried by a strap or chain. Museum reference H.KE 14.

Origins of the Monymusk reliquary

So much of the biography of this important object is unknown. The Museum acquired the reliquary in 1933 with the help of the National Art Collection Fund. Traditionally, the reliquary was associated with St Columba. It was identified as the Breacbennach (battle standard) carried at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. However, there is no clear evidence for this link, and it seems to be wishful thinking by scholars in the 19th century.

Monymusk is one of a small number of early medieval reliquaries known as ‘house-shaped shrines’. However this description may be misleading. The shape of the reliquary is more likely to reference burial sarcophagi or (idealised) church buildings than houses. Theses reliquaries are labelled ‘Insular’, indicating that they were made in Britain or Ireland. However with the exchange of ideas and art-styles in the early medieval period it is difficult to be more specific about its origins.

Construction

The reliquary is a complicated and fragile object. It is made from silver, copper-alloy (some gilded), enamel, glass, wood, and iron. In its original form there would have been at least 56 pieces. Today, excluding the pins holding the shrine together, 41 separate components survive.

The wooden core of the reliquary behind the damaged copper-alloy side plate. Museum reference H.KE 14.

The core of the reliquary is a wooden box and lid, each carved from a single piece of yew. These are encased in metal plates, with silver on the front of the box and lid, and copper-alloy on the other faces. The silver plates are decorated with very faint animal interlace and held in place by metal frames secured by pins.

Only four of the six original mounts attached to the front of the reliquary have survived. One of the two decorated plates attached to the narrow sides of the reliquary is also missing. A chain or strap would have attached to this plate to allow the reliquary to be carried. To open the reliquary a small rod was drawn out of the left side, freeing a metal clasp embedded inside the lid and front wall of the box.

A close-up view of animal interlace on the silver plates, and one of the surviving mounts. Museum reference H.KE 14.

When was it made?

The Reliquary is usually thought to date to the 8th century AD. Our research suggests the reliquary has in fact been reworked over its life. The round mounts on the front of the box and lid are made from reused pieces from an older reliquary. At some point in the object’s history, circular frames were added to these, and a new set of three rectangular mounts were made to match. Elements of the reliquary are therefore slightly older than the 8th century. The object as it survives today may date to the 10th to 12th centuries.

Nine similar reliquaries survive today, together with a growing body of shrine components. Most were assumed to have been made in Ireland. Monymusk is usually regarded as a Scottish exception. The reliquaries were widely distributed and there are examples from Britain, Italy, and Scandinavia.

Opening the Monymusk reliquary

The Monymusk reliquary would have opened easily, suggesting regular access to its contents. This contrasts with book shrines and some other types of reliquaries that encase the relics and were not intended to be opened. One can imagine the opening of the Monymusk reliquary, and the revealing of hidden and holy contents, as a performance and part of other early Christian rituals.

The reliquary open, showing the inside of the lid. Museum reference H.KE 14.

Decoration

The decoration of the Monymusk reliquary emphasises the front face of the box and lid. On opening the box these parts separate to reveal the contents. Silver (rather than copper) plates decorate the front face and lid. This silver dramatically reflects the light. Early Christian craftworkers often used shining precious metals and gleaming gems on reliquaries. This was a metaphor for divine light and sanctity. It was also a means of radiating these holy qualities to those viewing them. Clusters of stones on reliquaries shone with light and were considered to have miraculous powers. This light also complimented the relics inside the reliquary, but the decoration is most impressive when the reliquary is closed.

Christian imagery

Unlike some other early Christian reliquaries there are no figural or narrative scenes on the reliquary. There is also no decoration specific to the saint or objects once enshrined in the box. This is also true of the other Insular house-shaped reliquaries. Opting for abstract designs such as interlace and entwined animals, rather than explicit imagery depicting the purpose of the box, was deliberate. This contrasts with carved stones from the period which do depict people and events from the scriptures, alongside interlace and geometric designs.

It may seem strange that such an important Christian object has no overt Christian decoration. Archaeologist Robert Stevenson was first to recognise the subtle Christian imagery on the reliquary. He identified a Christian cross formed by the spaces between the interlace strands on the centre of the reliquary’s ‘roof’ .

The interlace panel on the top of the reliquary roof contains a hidden cross. Museum reference H.KE 14.

This forming of crosses ‘in reserve’ between interlace strands is now recognised as a common feature of Early Medieval illuminated manuscripts, metalwork, and sculptured stones. A pair of birds’ heads, interlacing around a central jewelled setting, act as a terminal to each end of the reliquary’s roof. These birds face inward and towards the interlace panel with the ‘hidden’ cross.

One of the interlacing birds on the reliquary’s roof bar that flank the interlace panel with its hidden cross. Museum reference H.KE 14.

Subtle and complex imagery characterises much of early Christian art from Britain and Ireland. In Insular manuscripts, a central cross flanked by two identical creatures, often peacocks, depicted the faithful being drawn to Christ. It's possible that this aspect of the reliquary’s decoration held a similar meaning. It requires the viewer to take time to look, untangle and contemplate. Finding this symbolism on the reliquary for the first time would have taken more than a quick look.

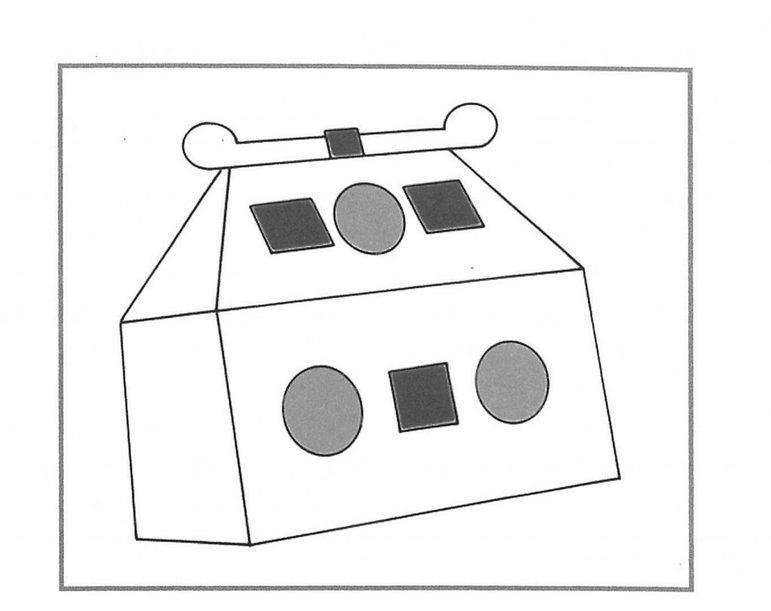

The reliquary mounts shaded to show arrangement in a cross (dark grey).

Decorative mounts

On the closed reliquary, the decorative mounts on the lid and box and the interlace panel on the roof bar can be interpreted as a Christian cross. The mounts can also be read as two separate groups of three – three circular mounts, and three rectangular mounts, both arranged at the points of a triangle. The design of each of the two types of mounts also emphasises these decorative principles in miniature. The circular mounts have three panels of enamel, while the rectangular ones have four, with the spaces forming a subtle cross-shape.

The top of the decorated side plate features a motif of three interlocking spirals. This was a common design in early Christian insular art. An obvious Christian interpretation for these designs is an allusion to the holy Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The central and interwoven Christian themes of the Crucifixion and the Trinity are visually combined through these mounts.

The frames of the mounts were originally gilded but only traces now survive. Museum reference H.KE 14.

The decorative mounts are some of the most worn parts of the reliquary. Here, the gilding is almost entirely removed. This suggests individuals who sought out the reliquary perceived the mounts as a special focus for veneration. Reliquaries were powerful objects. This restricted wear from repeated touching and rubbing of certain parts provides rare hints about the personal beliefs of early medieval individuals.

The Monymusk reliquary is on display at the National Museum of Scotland in the Kingdom of Scots gallery.