Reduce, Reuse, Recycle: Repurposing plastic waste

News Story

Where does our plastic go? Dr Ali Clark considers how artworks by Oceanic artists made from recycled plastics present local solutions to a global problem.

In 2017 the UN released a report warning that by 2050 our oceans may contain more plastic by weight than fish. Plastics are the most common form of marine rubbish. It is estimated that over 8 million tonnes of plastic are entering the ocean each year.

Plastic is an ever-increasing component of the world’s oceans.

This waste comes from a variety of sources including the plastic bottles and bags we commonly use and discard to plastic nets used and abandoned by the fishing industry. Marine life can easily get caught in these abandoned nets or mistake plastic waste for food.

In 2020, National Museums Scotland acquired new artworks from Oceanic artists that reuse plastic waste found in the oceans surrounding their homes. The lives of Pacific peoples and Torres Strait Islanders are intimately intertwined with the ocean surrounding their islands. It has social, cultural and economic importance. While the ocean is a source of food and income, it is also linked with the ancestors and creation stories.

The ocean is also a source of materials used in cultural objects. For example, in the Torres Strait Islands, turtle shell was used to create unique masks worn in ceremonies. These masks represented ancestors and associated totems, often combining human and animal features. A healthy ocean is therefore very important for all aspects of life.

Contemporary practitioners, drawing on customary knowledge, are adapting plastics to create new cultural objects, demonstrating cultural resilience in a fragile world. These objects ask us to reassess our relationship to plastic.

Recycling and reusing

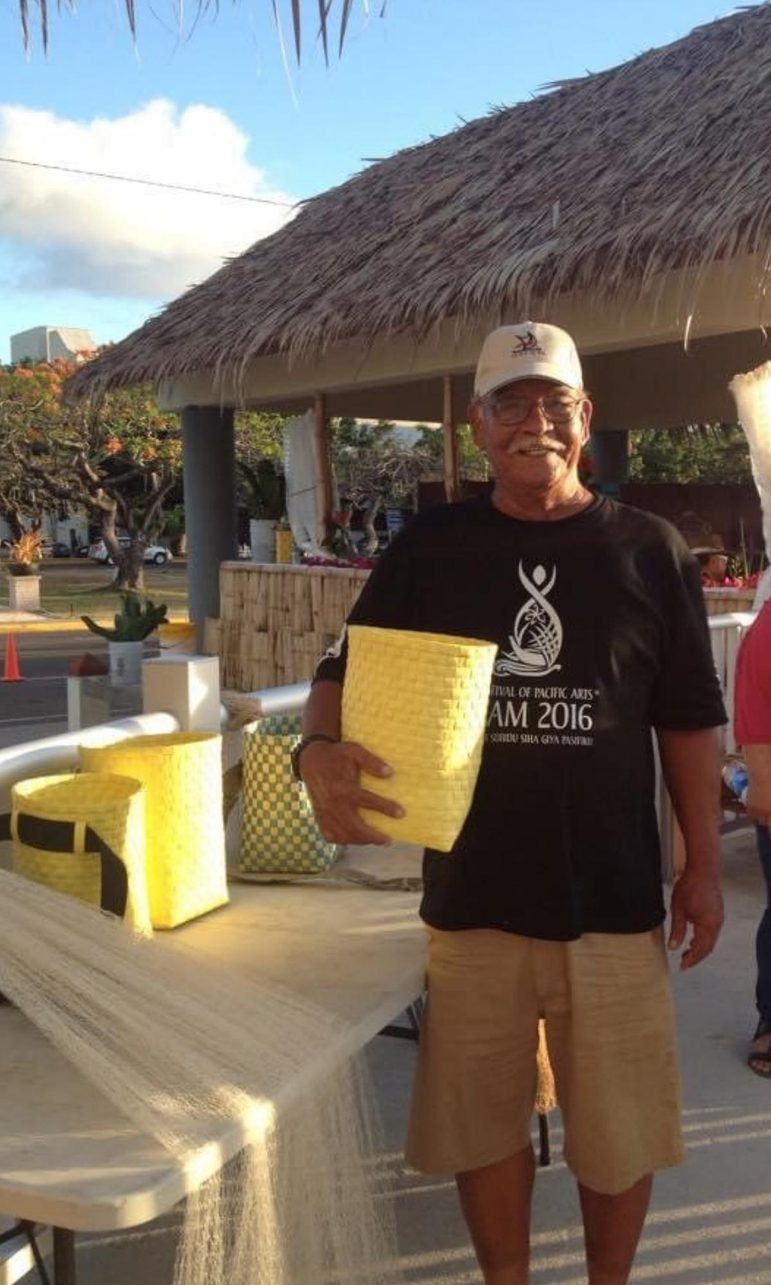

These fishing and gardening baskets are made from polypropylene pallet strapping, collected from the seas and the beaches on the Pacific Island of Guam. The strapping is used to secure objects to pallets during shipping and is often used to bind boxes of frozen fish. Straps that break during the shipping journey get lost or abandoned in the surrounding waters. The baskets, made by master fisherman and net maker Anthony C Guerrero, are contemporary versions of traditional Chamorro baskets and demonstrate the use of new materials found littering the natural environment.

Anthony C Guerrero holds one of his recycled plastic baskets. Guam, 2016.

An example of a basket woven from recycled plastics. Museum reference V.2021.9.2.

An example of a basket woven from recycled plastics. Museum reference V.2021.9.1.

The strapping is collected, cleaned and processed by Guerrero, before being cut into strips ready for weaving. The fishing baskets are used by the talayeru (net fisherman) in Guam. Looped onto a fisherman’s belt, the basket leaves the talayeru’s hands-free for throwing the circular net ringed with weights into the water. The basket is then used to hold fish caught in the nets. Both baskets are practical tools as well as political statements, reminding us that much of the plastic waste found in the Pacific is generated by the transportation and construction industries whose temporary presence in the Islands leaves a lasting legacy.

Ghost nets

The Torres Strait Islands, located off the north coast of mainland Australia, are a hot spot for ghost nets. Ghost nets are plastic fishing nets from the global fishing industry that have been lost or abandoned in the ocean, trapping fish and marine animals. Because of ocean currents and monsoon winds, nets from all over the Pacific Ocean end up in the waters around these small islands.

The nets entangle turtles, dugongs, shark and small fish. The nets also destroy coral as they get dragged across the reef by ocean currents. Turtles are particularly vulnerable and represent 95% of the marine animals found tangled in ghost nets each year, with an estimated 10,000 affected by the nets in the last decade. It is thought that these plastic nets can survive in the ocean for up to 600 years so projects like that run by Erub Arts can significantly benefit the turtle population.

An olive ridley sea turtle entangled within a ghost net.

‘Nguzu Waru Kazi (My Little Turtle)’ by Florence Gutchen, Torres Strait Islands, Australia, 2020. Museum reference V.2020.17.1.

For the past 10 years, artists based at Erub Arts have been cleaning up their oceans by collecting these ghost nets and reusing them to create new sculptural forms with traditional weaving techniques. The nets are collected by Erub Sea Rangers who clean and process them. The artists then weave and sew using the fibres from the nets to create the ghost net sculptures.

Each sculpture evokes the interconnection between the ocean, Torres Strait Islanders and caring for their island. The sculptures depict marine life found in the Islands and include turtles, sharks, fish, jellyfish and coral as well as the frigate birds which rely on the ocean for food. They help to raise awareness of the worldwide problem of ocean pollution.

Ethel Charlie works on ghost net fish.

‘Peter Piper’ by Jimmy John Thaiday, Torres Strait Islands, Australia, 2020. Museum reference V.2020.17.2.

In 2014, the then US President Barack Obama said in a speech at COP20 that “the nations that contribute the least to climate change often stand to lose the most”. Pacific Island nations and the Torres Strait Islands contribute less than 1.3 per cent of the plastic waste found in the world’s oceans yet they feel the impact of this waste in their environment the most. Anthony’s baskets and the ghost net sculptures from Erub Arts are local solutions to a global problem and stark reminders of the work that each one of us needs to do to reduce the impact of plastics on the environment worldwide. Now more than ever we need to be thinking local to act global.

‘Serina’ Jellyfish by Racy Oui-Pitt, Torres Strait Islands, Australia, 2020. Museum reference V.2020.17.3.

What can you do?

- Reduce your plastic use. Swap a single-use plastic bottle or hot drinks cup for a reusable one. 6 really good alternatives to plastic - Friends of the Earth

- Recycle any plastic waste you do produce. Recycling Sorter Tool - Zero Waste Scotland

- Find a beach cleanup in your area. Beach Cleans - Marine Conservation Society

Written by

Dr Ali Clark

Senior Curator, Oceania