The Qurna Burial: The discovery of a royal woman’s grave in Egypt

News Story

In 1908, an intact burial of a woman and a child was discovered in Qurna, Thebes, Egypt. Over a hundred objects were found in the burial, but the identities of the woman and child are a mystery.

The find was made by a team of Egyptian excavators and British archaeologist W.M. Flinders Petrie. At the time it was described as ‘the richest and most detailed undisturbed burial that has been completely recorded and published.’

The objects have fascinated researchers for years. They are an important source of information about a less understood period of Egyptian history. During this period, Egypt was politically divided. This was around 1600 BC, about 275 years before the burial of Tutankhamun.

The burial also tells us a lot about the cultural connections between Egypt and the powerful Kingdom of Kerma in Nubia (ancient Sudan).

Where was the burial discovered?

In the winter of 1908, William Matthew Flinders Petrie and a team of Egyptian excavators were working on the west bank of Thebes (modern Luxor). They were digging amongst the hills to the north of the road which leads to the Valley of the Kings. These smaller valleys had not been excavated before. Petrie hoped to find tombs in the area, but at first they found very little.

On 30 December 1908, the team uncovered a burial under a rocky outcrop on the north side of the valley. They removed several large boulders and found the burial in a shallow trench.

The excavation of the burial was given more care and attention than was usual at the time. This was probably because of the fragility of some of the objects. Nevertheless, according to Petrie, it was cleared in ‘around five hours’.

Photographs, descriptions, and illustrations show that the objects were tightly grouped in and around the woman’s coffin. The next day, the objects were drawn and photographed.

At the time, Egypt was under British rule. Finds from archaeological excavations were divided between the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the foreign excavation team. Since the head of the Antiquities Service did not want the burial group to be split up, he agreed that it could go to the UK provided it was kept together. Other UK museums were not willing to display the intact burial together, which led to National Museums Scotland purchasing the group.

Who was buried in the grave?

The coffin contained the remains of a woman, around five feet tall, aged about 18-25. With her was a white-painted rectangular coffin of a 2-3 year old child.

Both were wrapped in linen. They had been mummified but not successfully, so their remains were skeletal. The woman and child wore elaborate jewellery. The coffins were surrounded by objects, including furniture, imported pottery, and food.

The variety of objects buried in the grave suggest that they were members of the royal family at Thebes. The grave was also excavated near an area where other royal burials had been found. As such, the woman has become known as the ‘Qurna Queen’.

The coffin of the woman has a hieroglyphic inscription in a vertical column down the centre. A name should appear at the end of this, but it was damaged and lost. This is likely because of the placement of the child’s coffin on top. Since the text that would reveal the woman’s identity is gone, we can only suggest who she might have been.

The length of the gap in the inscription indicates that it contained a substantial title before the name. There is a tantalising hint provided by one hieroglyph. It suggests that it may have read ‘united with the white crown’, a title used for royal women at the time.

From other inscriptions and objects, we have put together a list of women who held this title to try and narrow down who the woman was. This list includes Haankhes, Nubemhat, and Sobekemsaf. It is difficult to be certain though as there may also be royal women who Egyptologists do not know about yet. They were all part of the Theban royal family and lived around the same time. It is likely some of them knew each other, with probably only a maximum of thirty years separating them.

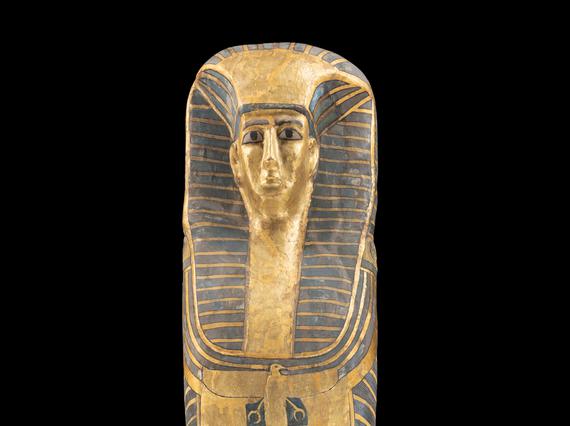

The coffins

The Qurna coffin is a beautiful example of a style known as a rishi coffin. This type of coffin was common in this period (c. 1700-1550 BC). Rishi is the Arabic word for feather, an apt term for the large, feathered wings which wrap around the lid of such coffins.

There are several theories about the meaning of the feather pattern. It could indicate an association with the ba, an aspect of the person’s spirit that could take the form of a human-headed bird. Or the bas of the gods Osiris and Ra, as referenced in a funerary spell from this period.

The Qurna coffin is large, measuring over half a metre taller than the woman who was buried in it. It was made from two whole tree trunks which were skillfully carved to fit together. The base is made from sycamore fig and the lid from tamarisk. The lid is gilded with gold leaf and painted with expensive pigments, particularly Egyptian blue and orpiment yellow.

The coffin shows the owner wearing a striped royal nemes-headcloth and a large beaded collar. On her chest is a gilded vulture with its wings outstretched.

The foot of the coffin is decorated with figures of two mourning women, probably the protective goddesses Isis and Nephthys. The base of the coffin is painted uniformly in blue, with a red line along the lip. The line was intended to provide a magical protective seal.

When the coffin was excavated, some areas of the paint and plaster had been worn away. They were later restored by conservators. The child’s coffin is much plainer than the woman’s. The white plaster which covers it hides planks and dowels of exotic woods such as East African ebony and cedar from Lebanon. It is shaped like a temple shrine.

The jewellery

The woman wore a magnificent set of jewellery. This included a gold necklace, two penannular gold earrings, four gold bangles, an electrum girdle, an electrum button, and a glazed steatite scarab.

The necklace is formed of 1699 individual gold ring-beads strung in four strands. It was secured with a clasp ingeniously designed to blend in completely with the ring-beads.

The necklace and earrings must have been almost entirely new or very little used. The bangles, however, show wear marks indicating the woman wore them regularly. The girdle shows so much wear that it may have been handed down as an heirloom.

The ‘Qurna Queen’ would probably have been at the cutting edge of fashion in her time. She wore very early examples of earrings which only became common after her lifetime. The style of bead used on her girdle (known as ‘wallet beads’) are probably the earliest surviving examples.

The child wore a gold/electrum necklace, two gold earrings, three ivory bangles, a faience bead girdle, and faience bead anklets.

The girdle suggests that the child was considered female.The earrings were probably re-purposed necklace clasps, serving as stand-ins. Even though we cannot be sure about the child’s identity, their jewellery gives us some clues. Their set of jewellery was intentionally assembled for the joint burial from reused and recycled elements. This suggests that it was intended to link the identities and status of the woman and child.

Objects discovered in the Qurna burial

The woman and child were buried with grave goods that indicate exceptional wealth. These include luxuries as well as more everyday objects like baskets, fruit, and even a ball of string.

Numerous carved stone vessels held cosmetics, some of which are still sealed with their contents intact. A beautiful bowl made of a stone called anhydrite is decorated with figures of baboons. A container made from a cow’s horn is fitted with an ivory carving of a bird’s head topped with a spoon and a small hole to allow the contents to flow into it.

Some items are extraordinary because they are so seldom preserved elsewhere. Ten net bags made from linen string were used to hold various pottery vessels, suspended from a wooden carrying pole. Similar net bags are known from both Egypt and Nubia.

Furniture was also found in the burial. While the three stools might seem rather ordinary, wood was scarce in Egypt, so any furniture would have been relatively expensive. Most people made do with sitting and sleeping on the ground, sometimes on woven reed mats. These stools are made from cedar imported from Lebanon. They would have been particularly costly and desirable. The beautifully carved cow or bull feet on the largest stool had gone out of fashion in Egypt, but were popular in Nubia at the time. This may indicate influence from Nubian fashions.

A headrest was also found. It was used to support and protect the head during sleep, and it might have had linen padding. It is made of local acacia wood, but inlaid with ebony and ivory which were expensive imported materials.

Triangle pattern decoration occurs across both Egypt and Nubia early in their history. But at the time of the burial, this pattern of inlays is known only in Nubia. All these items of furniture suggest influence from Nubian culture.

Image gallery

Cultural connections between Egypt and Nubia

Nubia was Egypt’s nearest neighbour to the south, in the area of northern Sudan and southernmost Egypt today. The burial of the ‘Qurna Queen’ contained six exquisite beakers that came from the Kingdom of Kerma in Nubia.

The burial itself is Egyptian in style. But the presence of Nubian pottery in the burial prompted theories about the identity of the woman. Some argued that she was a Nubian princess who married into the Theban royal family. However, this theory assumes that the Nubian Kingdom of Kerma was culturally and politically subservient to Egypt.

Earlier in the 20th century, the colonial attitudes of European and American Egyptologists meant that they assumed that Egypt was culturally linked to Europe. This led them to believe that Egypt was more ‘civilized’ than the rest of Africa. Indeed, the first excavator of the site of Kerma in Sudan originally assumed that it was an Egyptian colony. This has since been proven to be incorrect.

Further excavations have shown that Kerma was the site of a wealthy and powerful kingdom with its own unique culture. The Egyptian objects found there seem to be luxury imports that expressed their owners’ status and wealth.

We now know that Kerma was just as powerful and influential as Egypt. So it makes sense that Nubian items would have been considered desirable. The delicate and beautifully formed Kerma beakers have been described as 'among the finest ceramic art forms ever created'.

Other items from the burial considered either Egyptian or Nubian are actually not so easily categorised. Earrings did not exist in Egypt before the Qurna burial. The idea of earrings seems to have come from Nubia or western Asia. The inlaid headrest looks Egyptian but has Nubian-style inlays. The cow or bull-legged stool is a style that was used in Egypt several hundred years earlier, but was popular in Nubia at the time. The carrier net-bags have parallels in both Nubia and Egypt.

All these objects may indicate shared aspects of Nubian and Egyptian culture. Although Egyptology has often approached Nubia as ‘foreign’, re-examination of the objects suggests a greater extent of mutual influence and shared cultural heritage across the Nile Valley.

Why is the burial important?

The objects from the burial have helped us reassess Egypt’s cultural connections with Nubia. But they tell us so much more. The Qurna burial had remained untouched since antiquity, like an ancient time capsule. This means that many of the objects have been useful in dating and interpreting similar objects in other museum collections.

The burial dates to a period when Egypt was politically divided between competing rulers in different parts of the country. This included occupiers from Western Asia in the north. Thebes was the seat of power for kings who ruled the southernmost part of Egypt. Known as the Second Intermediate Period, Egyptologists know less about this period. The lack of political stability meant that fewer objects and texts survive from this time.

The burial group is an important source of evidence. It shows that the Theban royal court was not completely isolated or at conflict with its neighbours. They had access to skilled craftspeople, resources, and trade connections beyond Egypt, but they also reused and recycled things that were harder for them to access.

Although the identities of the ‘Qurna Queen’ and child remain a mystery, their burial sheds light on many fascinating aspects of ancient Egyptian and Nubian culture.

The Qurna Burial at the National Museum of Scotland

The Qurna burial is the only intact royal burial group outside of Egypt. The group is on display in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

Ancient African Queens: New perspectives on Black History

Discover more about the Qurna Burial in this recording of the online event Ancient African Queens: New Perspectives on Black History.

Dr Margaret Maitland and Dr Solange Ashby examine biases and the cultural connections between ancient Egypt and Nubia. They apply new perspectives to historic collections, in recognition of the importance of Nubian material culture.

This event originally took place on 27 October 2022 and was chaired by Professor Katherine Harloe.