The ancient craft of barkcloth across the world

News Story

Barkcloth is a type of natural cloth made by stripping, soaking, and beating or weaving lengths of the inner bark from trees such as paper mulberry, ficus, and elm.

It is produced in countries located along a tropical 'barkcloth belt'. This includes the Pacific Islands, Japan, Taiwan, Island Southeast Asia, India, East, Central and West Africa, tropical South and Central America, and the Caribbean.

The changing use of barkcloth can be attributed to the introduction of cotton fabrics, changing lifestyles, and the loss of trees needed for production. Today barkcloth is still produced in some countries in smaller quantities but remains integral to many aspects of life.

How is it made?

Barkcloth is produced by cleaning bark stripped from its outer layer and boiling or steaming it. It is then beaten over a log or hard surface for several hours with heavy beaters made from wood, horn, stone, bone, or shell. This causes the fibres to soften, stretch and fuse together.

Barkcloth is predominately a type of non-woven cloth. The exception is Ainu barkcloth from Japan, which is woven rather than beaten.

The dried cloth is often decorated. It has a variety of uses across the world including for masks, clothing, bedding, mats, tablecloths or souvenirs for tourists.

Image gallery

The global barkcloth belt

Africa

There were once large centres of barkcloth production in western, central, and eastern Africa. This included the Congo Basin in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, and Zambia. Production was also known in West Africa among the Asante of Ghana, and on the island of Madagascar.

It had a wide range of uses. It was often worn wrapped around the waist, and under the arms or toga style. It had a variety of domestic uses including screening and bedding. Barkcloth also played an important role in ceremonies for birth, initiation, marriage, and funerals.

From the mid-19th to the early 20th century, imported cotton fabrics became more widely available. More modest styles of dress were promoted due to the influence of Muslim and Christian religious practice. Barkcloth production and use declined.

Among many, barkcloth began to hold ambivalent associations with the past. Today barkcloth survives among very few communities where it continues to hold special significance and positive links with long held cultural traditions.

In the Ituri rainforest in the Democratic Republic of Congo, loincloths of barkcloth from a number of ficus species are decorated with intricate painted patterns relating to the natural world around them. These are worn by the Mbuti for ceremonies and performances associated with community rites of passage.

Among the Baganda in the Masaka region of southern Uganda, large rectangles of the distinctive undecorated, reddish brown barkcloth from the mutuba tree (ficus natalensis) is produced. It continues to be a very visible symbol of monarchy and royal heritage.

Recognition of the significance of barkcloth production in 21st century Bugandan cultural identity was acknowledged in 2005 by UNESCO. Ugandan barkcloth making was proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Indonesia

Barkcloth was once produced throughout Southeast Asia. There was great diversity in regional styles. From reddish-brown cloth in the Nicobar Islands to embroidered garments in Laos, regional styles developed according to local customs and needs.

On the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, barkcloth was commonly used for clothing and domestic items until the end of the nineteenth century. In the highland communities of Central Sulawesi, clothes for special occasions were made from soft, white barkcloth. They were painted with bold, symbolic designs, and bright colours. Intricately patterned sigas (men’s headdresses) and halili (women’s blouses) would have been worn at feasts and important life events. Decorated with geometric motifs and symbols like buffalo horns, four-petalled flowers and suns, the cloths also contained spiritual and ritual importance.

From the early twentieth century, the Dutch colonial government took a more active role in Central Sulawesi. Christian missions were established in the interior. Traditional ways of life and dress were discouraged and imported woven textiles were introduced. Barkcloth production and use declined.

Today, the Lore region of Central Sulawesi is one of the last places that still produces and uses barkcloth in Indonesia. It is now recognised and appreciated as a distinctive cultural heritage. Makers from Central Sulawesi have exhibited their cloth in national museums and private galleries in Jakarta. It has also been used by contemporary artists, featuring in costumes and installations in international exhibitions.

In recent years, the craftsmanship and sustainable quality of barkcloth have been promoted by artisans in Bali. They partner with makers in Sulawesi to produce bags and accessories. Although Indonesian barkcloth is no longer produced and used on the scale it once was, it continues to be valued as a unique regional art form with environmental relevance for the future.

Japan

Attush is the Ainu term for barkcloth. It has been made and worn by the Ainu, Indigenous people in northern Japan, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands, for centuries. The climate of these regions and the hunting, rather than agricultural, lifestyle of the Ainu are not conducive to producing silk or cotton, which is commonly used in mainland Japan. Ainu clothing is made from barkcloth, animal skin or, from the 19th century, imported cotton.

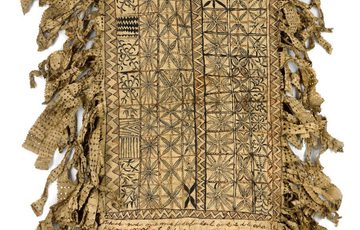

The Ainu produce attush, an attractive buff or golden fabric, from the inner bark of young mountain elm trees. The elm bast fibre, known as ohyo, is soaked then processed into thin strips which are woven on a backstrap loom. The resulting fabric, mainly used for robes, is lightweight yet durable. Ainu robes have a similar overall shape to robes, or kimono, worn by wajin (ethnically Japanese) in mainland Japan. However, the sleeves of Ainu robes are tapered. This uses less material and is more practical when carrying out tasks.

Although the robes are worn by men and women, it is the women who weave the attush as well as make and decorate the robes. Indigo-dyed cotton, acquired through trade, is often appliqued with embroidery to create abstract designs. The designs are said to variously represent thorns, eyes, stars, and possibly animals. These decorative patterns demonstrate the artistic skills and creativity of the maker and are said to please the kamuy (spirits or gods). The patterns are concentrated around the openings (hem, cuffs, and collar) of the garment to provide a protective element from harmful spirits.

Highly decorated attush robes are reserved for ceremonial occasions. Simpler ones are worn in daily life. However, due to the colonisation and forced assimilation of the Ainu in Hokkaido by mainland Japanese in the 19th century, the wearing of attush and other Ainu robes has dwindled. The traditional weaving and embroidery skills necessary to make them has also declined.

Pacific Islands

Pacific Islanders have been making barkcloth for millennia. It was produced in large quantities across the islands of Polynesia and Melanesia. Micronesia is not known to be a barkcloth producing area due to the lack of appropriate trees.

Often referred to generically as tapa across the Pacific Islands, many Islands have their own names for the cloth. These include Fijian masi, Hawaiian kapa, Samaoan siapo, Niuean hiapo, and Tongan ngatu.

The cloths that were created across the Pacific varied in size and intended use. Whilst sheets of barkcloth were made by most barkcloth producing Islands, many Islands also used barkcloth in other ways.

Image gallery

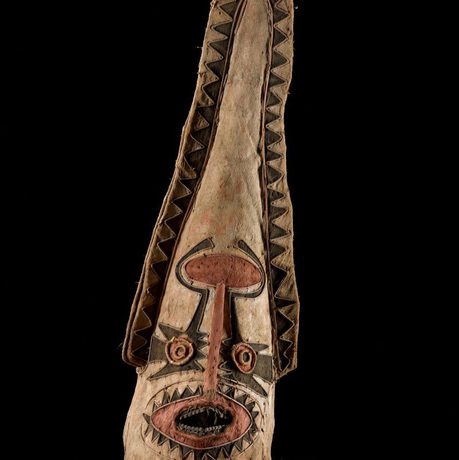

In Papua New Guinea barkcloth was draped over fibre frames to create visually arresting ceremonial masks. In Niue barkcloth is sometimes used to create tiputa or poncho. In Tuvalu barkcloth was used for delicately embroidered belts. Huge lengths of barkcloth would have been presented as gifts at major occasions such as weddings in western Polynesia. In Fiji barkcloth was even used for printing newspapers onto.

Some Pacific barkcloths were highly decorated. Others were left plain stained simply but powerfully with turmeric or other natural dyes.

The production and use of barkcloth declined in many Pacific Islands during the 19th century. This was due to the introduction of cotton fabrics by European missionaries, traders, and government officials. Today it is being revived in places such as Hawai’i, Aotearoa New Zealand and Niue, and remains strong in the Islands of Papua New Guinea, Tonga, Sāmoa, and Fiji.

Jamaica

The tradition of making barkcloth was introduced to Jamaica in the 17th century by African slaves from Ghana and the Congo taken to labour on sugar and coffee plantations. The practice was modified to suit the natural environment of Jamaica and its resources.

Lace bark, as it became known, was made from the bark of the fibrous lagetto tree. Its most common use was for the production of household items and clothing. Unlike other barkcloth, lace bark was made by teasing out the refined fibres of the lagetto bark by hand. The fibres were then dried in the sun. The end result was a fine cloth which resembled lace or linen, hence its name.

By the end of the nineteenth century the trees became scarce due to overuse. The production of lace bark rapidly declined. Recently a small grove of lagetto trees was discovered in Jamaica. There is currently a petition to UNESCO to have the area designated as a world heritage site.

Barkcloth on film

Discover the process of making and designing siapo (barkcloth) in American Sāmoa with siapo artist Reggie Meredith Fitiao.

A note on this film: In April 2020 National Museums Scotland, in partnership with the University of Glasgow, was due to hold a barkcloth masterclass led by Samoan artists Reggie Meredith Fitiao and Ulisone Fitiao, exploring the art of Samoan siapo. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic this event was cancelled and instead Reggie and Ulisone created this video.