A unique 3000-year-old hat made of horse hair

News Story

In 1953, when Donald John Mackay was out peat-cutting near Kirtomy in the old county of Sutherland with his 10-year-old daughter Babette, his spade brought up a curious mass of hair, bound into coils. Little did he know that he had just found Scotland’s earliest recognisable garment, a 3000-year-old hat made from horse hair.

The discovery

The mass of hair was spotted by eagle-eyed Babette as her father’s spade cut into peat at a depth of around 1.22 metres. DJ recognised that this strange and fragile construction of hair, held together by peat, looked like a hat. He took it home and told a local schoolmaster, Donald MacLeod about his findings. Mr MacLeod reported the find to staff in the (then-named) National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland (NMAS) in Edinburgh. NMAS then acquired the hat in 1961.

Disentangling the hat

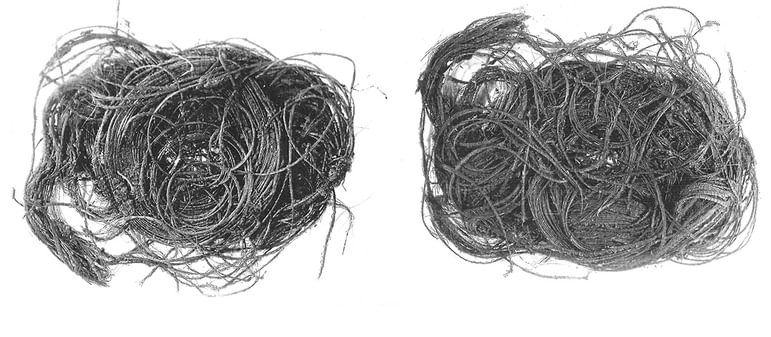

Photographs taken when it entered the museum show how it looked like a ‘confused and dilapidated mass’ of bound hairs, as it was then described. In the wrong hands, this could have ended up as a spaghetti-like mess. Fortunately, the hat was delivered to Audrey Henshall – who was Assistant Keeper and specialist in ancient textiles.

Audrey was able to confirm that it was, indeed, the remains of a hat. With her customary care and meticulous attention to detail, she undertook a forensic deconstruction of the mass of hair. As she worked, Audrey took detailed notes and measurements. These have proved to be invaluable to our recent research, since without them, the remains can be hard to decipher.

Image gallery

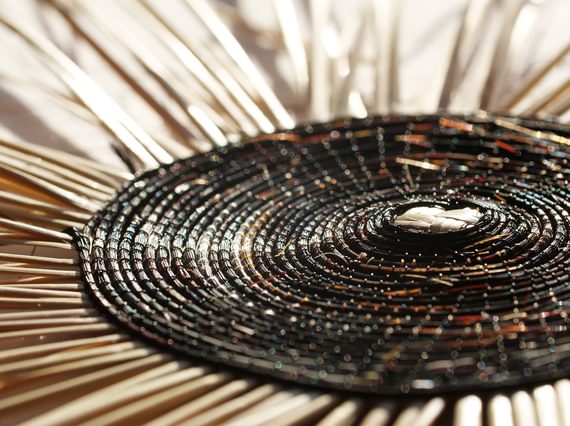

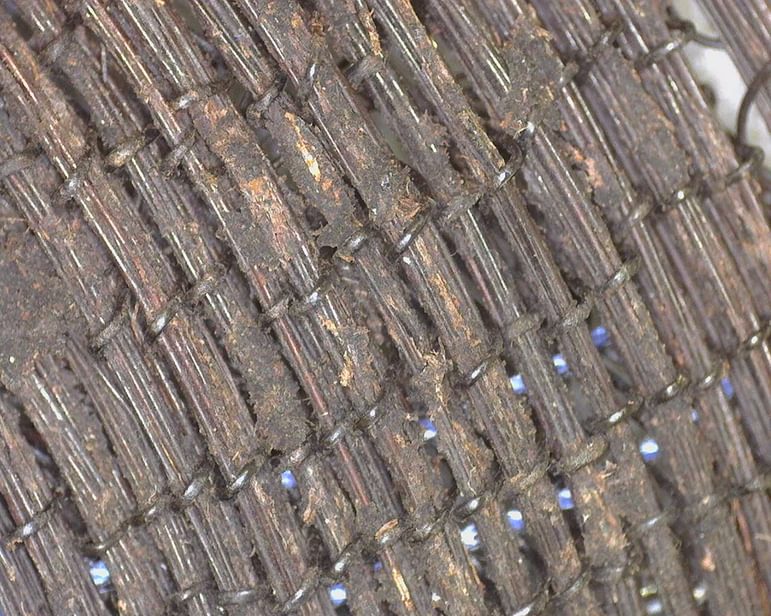

The crown of the hat consists of a tightly-spaced coil of ‘cords’, each cord comprising around 12–15 individual hairs, bound around by a further hair. The very centre of the crown survives as a small spiral with a hollow in the middle. The crown could have been flat or slightly domed.

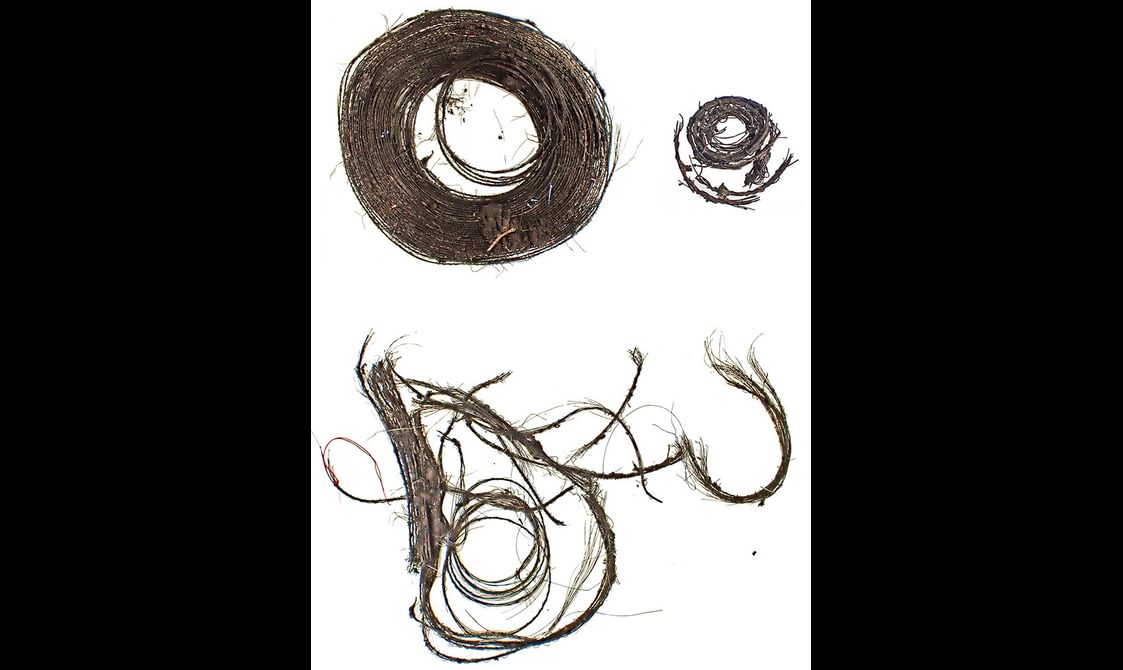

Below the crown, Audrey found a hoop of coiled cords. The diameter at the bottom (inner edge on the photo) was slightly narrower than that at the top (outer edge). This indicated that the wall of the hat sloped in at this point. With this, as with the rest of the hat, Audrey had to take steps to prevent the structure from falling apart, as it was only peat that kept the cords in position. She bound the cords together with thin wire and added coloured cotton to indicate how the different parts of the hat connected with each other.

Below that, she found two larger ‘hoops’, forming the upper and lower parts of the hat’s brim. This double layer of coiled horse hair ensured the hat would look equally good when viewed from below as from above. The coils here were bound with double hair loops.

Audrey also realised that these coiled cords must have been attached to something else that had decayed away completely in the peat. She was able to tell this because the loops formed by the hair strands that were used to bind the bundles of hairs in the cords were slightly bigger than the cords themselves. Each loop must therefore have passed underneath another substance such as a piece of straw, 1.5–2 mm in diameter, that ran crosswise to the coils. The infrastructure formed by the pieces of straw gave the hat its rigidity. Audrey also noted that the bundle of hair in each cord had been fastened at one end with a knot. These knots were slipped under the hat so that they would not be visible.

After measuring and documenting the parts of the hat, Audrey created a full-sized paper mock-up.

The use of horse hair in garments

Wishing to find out what the source of the hair had been, Audrey consulted fibre expert Michael Ryder. It was confirmed that it had come from the tail of one or more horse (or pony). Audrey also started looking into other ancient non-woollen garments, including a tasselled horse-hair belt from Cromaghs, County Antrim, curated by the National Museum of Ireland. Clearly she had intended to write up her notes for an article in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland but, due to other work commitments, this never materialised. The hat, and her notes and drawings, were put away in the store and there they remained, untouched, until 2014 when the contents of the store were moved to a new location.

Audrey had no way of knowing how old the Kirtomy hat was, and so it had been stored along with medieval and later objects. During the store move, the hat was shown to Dr Alison Sheridan who was then Principal Curator of Prehistory and who realised it might be considerably older. Alison arranged for a hair from the hat to be radiocarbon-dated, and the result came back as 1190–920 cal BC. This placed it in the Late Bronze Age, roughly contemporary with another object featuring horse hair in the collections - the so-called ‘Sheshader Thing’ from the Isle of Lewis - which Alison previously had radiocarbon-dated, to 1270–820 cal BC.

In 2024, a fresh round of research into the Kirtomy hat commenced. In order to double-check whether the original identification of the hair species as equine was correct, a sample was examined under the NMS’ scanning electron microscope, but it was found that the hair’s surface was too degraded to retain any tell-tale surface features. However, diameter measurement using the NMS high-powered Keyence digital microscope, together with analysis at York University, confirmed that the hat is indeed made from horse hair. From its length we know the hair must have come from the tail.

Horses in the Bronze Age

The discovery that the National Museums Scotland collections contained not one but two Late Bronze Age artefacts made using horse hair was remarkable. These objects are among the earliest evidence for the presence of domestic horse in Britain and Ireland. It is now known, from a growing number of radiocarbon dates, that the domestic horse is likely to have arrived on our shores between 1460 and 1260 BC. We may use the term ‘horse’, but actually these creatures would have been pony-sized. Like the Exmoor or New Forest ponies, they would be no taller than around 13 hands (around 1.37 m) at withers height (the ridge between the shoulder blades).

Around the time when the Kirtomy hat and the Sheshader ‘Thing’ were in use, items of horse gear began to appear in the British and Irish archaeological record, including in the hoard of bronze artefacts recently found near Peebles, and in another bronzework hoard found not far away at Horsehope in the 1860s. . The evidence suggests that horses – precious possessions – may well have been used to pull prestigious vehicles belonging to Late Bronze Age VIPs. The Peebles hoard even includes a set of jingle plates, also known as a rattle plates, which will have been attached to a horse’s cheek-piece and would have jingled as it cantered along.

If, as seems likely, horses were being used as draft animals at this time, then it is likely that their tails would have been trimmed, to prevent them from getting caught in the equipment linking them to the vehicle – and so there will have been a supply of tail hair, available for use in hat-making (and possibly for other purposes too).

Reconstructing the Bronze Age garment

Textile and fibre expert Dr Susanna Harris and historical costumier Lilja Husmo were invited to take a closer look at the remains, with a view to Lilja recreating the hat. A grant from the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland enabled Lilja to undertake that work.

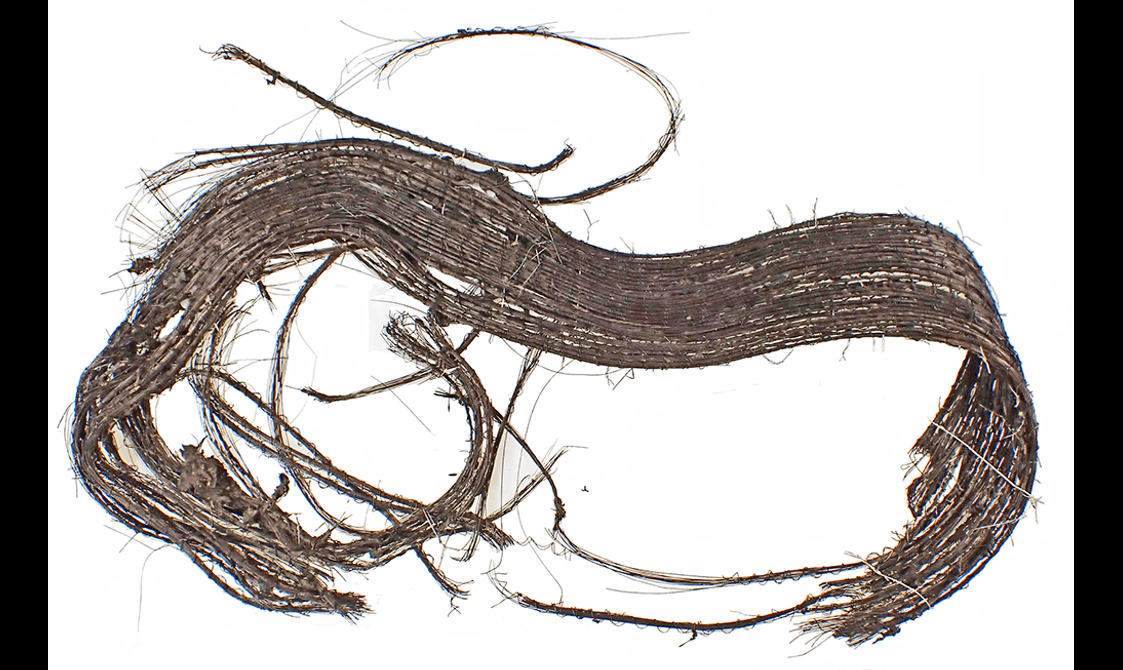

Susanna and Lilja concluded that Audrey had been spot on in nearly every detail of her work. Susanna was able to identify the technique used to create the hat as an example of ‘wrapped twining’. Wrapped twining is an unusual variant of simple twining. This particular technique is known from basketry, but never before known to have been used to make a garment in prehistoric Britain and Ireland. This was another ‘first’ for this remarkable artefact. Wrapped twining uses three sets of working elements: a passive element (or warp) that is bound by two paired elements (wefts), one rigid and one flexible. In the hat, the single or double hair used to bind each bundle in a cord makes up the flexible element, called the running weft, while the rigid weft is the knotted bundle of hairs. The warp will have been the straw (or similar) infrastructure.

Susanna was also able to confirm that the Kirtomy hat counts as Scotland’s earliest recognisable garment. It is not the earliest evidence for the twining technique more generally in Scotland. Objects featuring simple (not wrapped) twining of vegetable fibres have been found in Early Bronze Age cist graves at Crantit in Orkney and at Langwell in the old county of Sutherland. These could have been used as matting, lying under the body (at Crantit) or as covering it (at Langwell) – rather than as garments. Similarly, ox-hides have been found as a wrapping for human bodies in some high-status Early Bronze Age graves in Scotland and elsewhere, but this does not mean that they had necessarily been worn as garments.

After visiting the original hat pieces, Lilja began to create a reconstruction of the hat. She used millinery-grade straw for the infrastructure, splitting it and soaking it in hot water before use. Procuring horse tail hair proved to be more complicated than anticipated, especially as living horses and ponies need their tails as fly-swits. Some tail hair was supplied by Miri (or rather, by her owner Dr Julie Gardiner) and some pony tail hair was supplied by Gail Brownrigg. Nicole Petrie kindly permitted the tail of her beloved horse Casper to be used. It was particularly appropriate that Casper’s tail was used since, during his life, he had a fascination for people's hats.

Image gallery

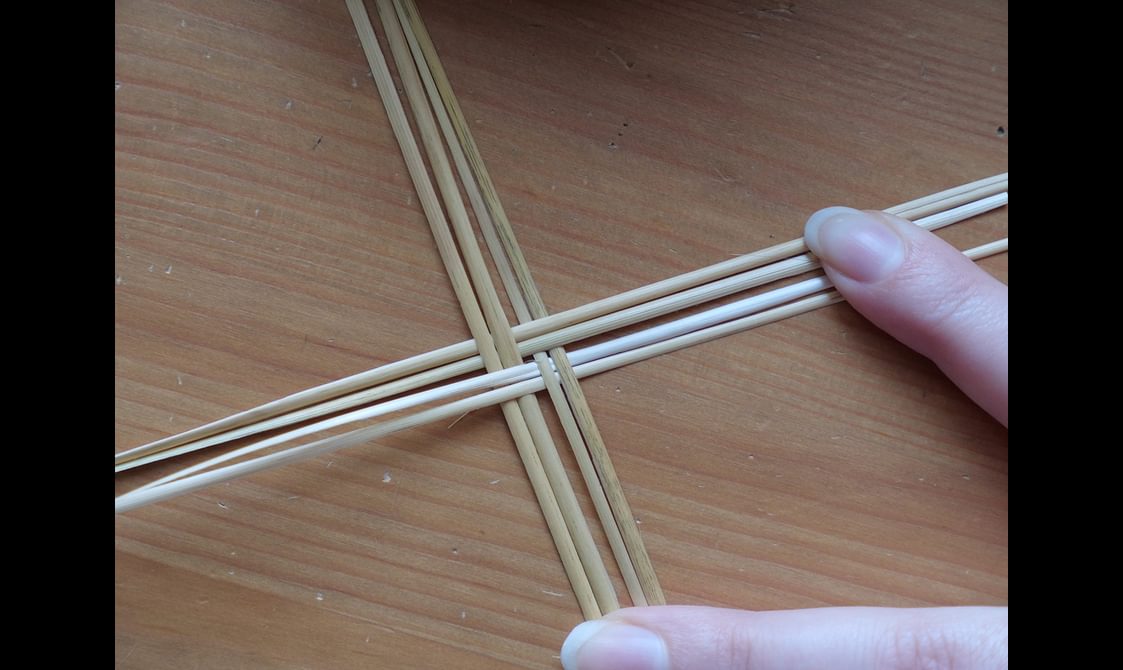

The first stage of creating the replica was to create a straw ‘spider’, to which the cord-coil of the crown was bound. More straws were then added. This accounts for the gap in the centre of the remains of the hat: it will have been occupied by the criss-crossed straw junction.

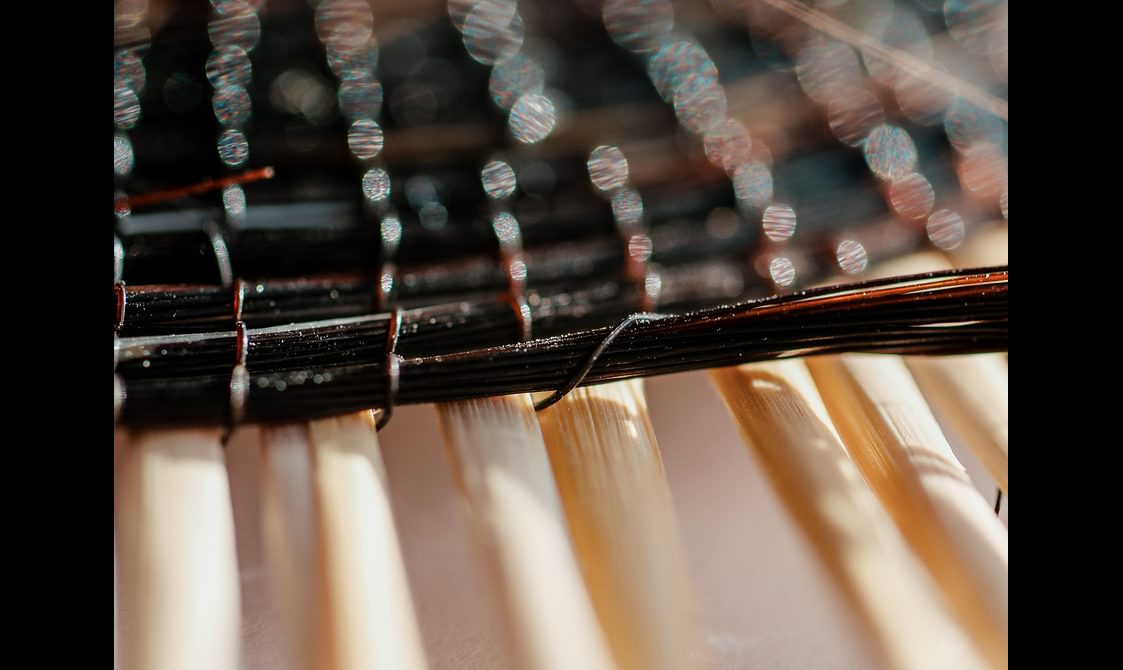

Splicing additional cordage was achieved by taking a bundle knotted at one end, placing the knot on the underside, then splicing it in among the ends of the preceding cord’s hairs. This binds all to the straw infrastructure with a single hair (or double, at the brim) from the bundle.

The coil-spiral was kept tight by pushing it towards its preceding position, to create a dense and neat surface. To change direction at the edge of the crown, the straw was steamed and bent, and this was repeated for the brim. Finishing off the brim will involve pleating the end of the straw back upon itself, as is the technique used with traditional straw hats.

Lilja has estimated that it could have taken an experienced worker around 40 hours to create the hat; each coil takes around 45 minutes to bind on to the infrastructure.

Questions still to be answered

The hat will have been made for an adult, by someone skilled in making such garments. There are many unanswered questions, though: how did it come to end up in a wet place? Did it blow off someone’s head? Was it owned by a member of the elite? Though there is other evidence for people’s presence in this part of Scotland, there is much that still remains to be discovered about Sutherland’s Late Bronze Age inhabitants. We're grateful, then, for Babette and DJ's one-in-a-million find which shows that Scotland’s peat bogs are not just good for the environment: they also contain precious ancient artefacts.

Written by

Dr Alison Sheridan

Research Associate