The story of the Lewis chess pieces

News Story

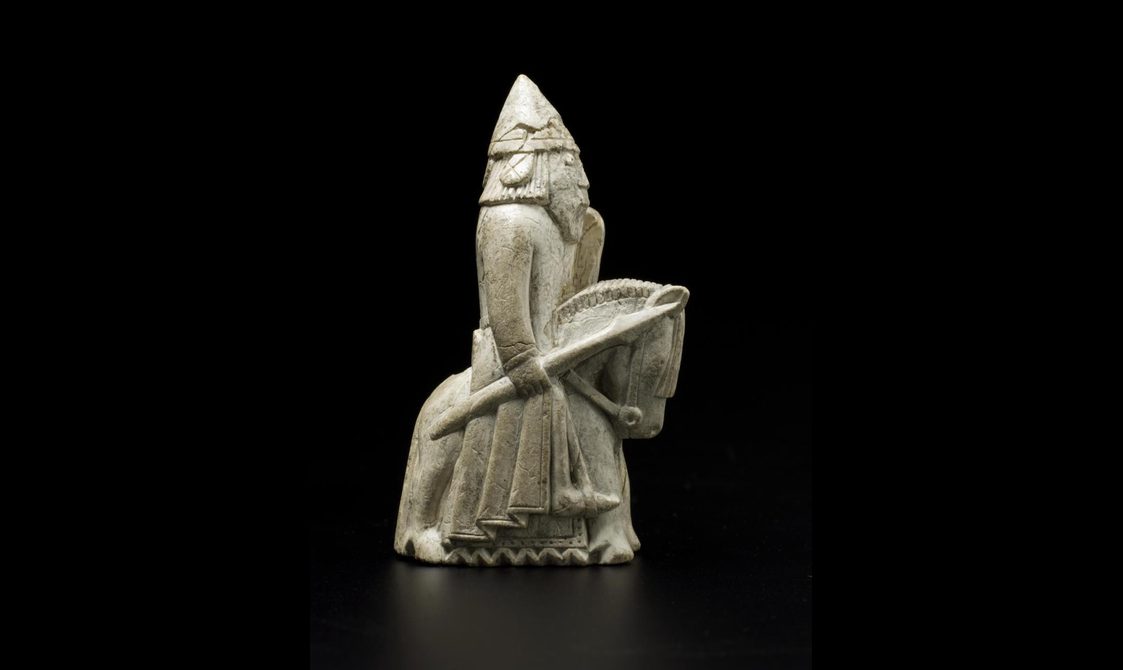

This group of eleven medieval chess pieces were part of a large hoard buried on the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. The hoard contained 93 gaming pieces in total, including from at least four chess sets as well as other games.

The chess pieces were probably made in the late 12th or early 13th century in Norway. They provide fascinating insights into the international connections of western Scotland and the growing popularity of chess in medieval Europe.

Medieval chess

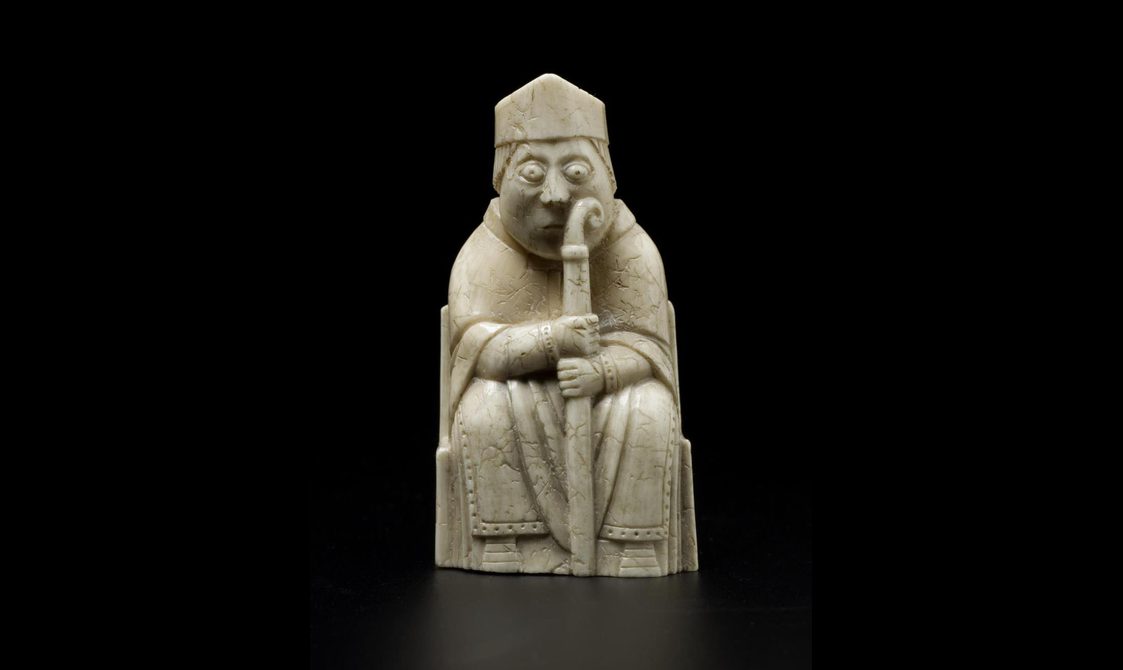

Chess is a very old game originating in the Islamic world. By the medieval period its popularity had spread across Europe. It became an important part of elite medieval society, a way of practising and demonstrating skill and strategy in a war-like setting. Many of the medieval chess pieces are familiar to those who play the game today.

Some of the chess pieces could also have been used to play the game of hnefatafl. Hnefatafl needs kings and pawns. A king, surrounded by his guards, has to reach a corner square before being captured by the opponent.

Boards for playing games have been found by archaeologists at medieval sites in Scotland, including monasteries like Whithorn (Dumfries and Galloway). At a monastery in Inchmarnock (Argyll and Bute) 35 gaming boards were found, including a stone inscribed with a grid for playing hnefatafl.

The Lewis hoard also contained pieces for playing the game of tables, a game similar to backgammon. Other medieval tables pieces have been found in Scotland, including an example decorated with interlace from the Isle of Rum.

Making the chess pieces

The style of the carving links the pieces to Norway. There is a similar chess piece from Trondheim, and the Lewis figures’ thrones are reminiscent of carving in medieval Norwegian churches.

Most of the Lewis chess pieces are made from walrus ivory. This was probably obtained in Greenland and traded back to Norway. Two of the pieces in our collection (and three British Museum pieces) are different, carved from sperm-whale teeth.

Hoarding the chess pieces

The chess pieces can be divided into groups based on their size and on the quality and design of the carving. This suggests there are pieces from at least four chess sets amongst the hoard. Differences in the pieces’ faces and clothes hint that the sets might have been carved by different people within a single workshop. If there were four sets buried in the hoard, a number of pieces are missing, including one knight, four warders, and 44 pawns.

The easiest way to distinguish between opponents pieces is through colour. Though traces of colour may have been visible when the pieces were discovered, they are not apparent today. Scientific analysis of some of the pieces has found traces of mercury. This suggests some may once have been coloured red with cinnabar (mercury sulphide).

Image gallery

Lewis in the 12th and 13th century

The pieces belong to the Scandinavian world, which at this time the Hebrides were part of. Around the time the hoard of chess pieces was buried, Lewis belonged to the kingdom of Norway. The culture was a mix of Gaelic and Scandinavian. Even after the Isles were ceded to Scotland in 1266, ties to Norway remained close and the bishops remained part of the bishopric of Trondheim. Other medieval chess pieces have also been found in the Western Isles, for instance, a walrus ivory knight from the Isle of Skye.

We do not know who buried the pieces or why. They may have been the property of a merchant, sailing from Scandinavia to Scotland, Ireland or the Isle of Man to sell these highly-prized playing sets. But given that Lewis was home to powerful people with close ties to Norway at this time, the playing pieces may instead have been the treasured possession of a local leader, a prince or bishop perhaps.

The discovery of the hoard

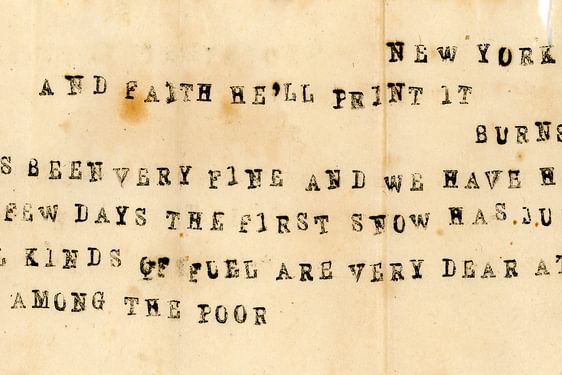

There are many unanswered questions about the hoard’s discovery. It first came to light when the pieces were exhibited in Edinburgh at the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1831. They were on display with the permission of Mr Roderick Rirrie of Stornoway, Lewis.

The hoard seems to have been found near Camas Uig (Uig bay), on the west side of the island. But there are conflicting accounts of the discovery. One mentions a ruined monastery while another describes a buried structure, reminiscent of an Iron Age souterrain, an underground stone-lined cellar. None of the authors seems to have visited Lewis, leaving much uncertainty about where and how the hoard was found. Some accounts name the finder as Malcolm MacLeod from the nearby settlement of Peighinn Dhomhnuill. But information about him is scarce.

Only months after its discovery, the hoard was broken up and sold by Mr Ririe. The pieces in our collection passed through several private collections before being acquired in 1888. The British Museum had bought the rest of the hoard in 1831 and 1832. Six pieces are currently displayed in Museum nan Eilean on the Isle of Lewis, on loan from the British Museum.

Inspiring stories

The chess pieces have inspired many stories since their discovery. One of the earliest is the Gaelic legend An Gille Ruadh (The Red Gillie), set in the 17th century. This told that the hoard was found when a servant spotted a sailor fleeing his ship with a bundle of valuables. The sailor was killed for his treasure. The servant could not return and collect it and was later sentenced to death for his crime. This legend shows that the hoard had become part of the folklore of the people who lived at Uig.

In 2001, the Lewis chess pieces reached new audiences with the release of the first Harry Potter film, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Sorcerer’s Stone in the American release). Harry and Ron play wizard’s chess, where the pieces are enchanted and move by themselves.

The Lewis chess pieces are on display in the Kingdom of Scots at the National Museum of Scotland.