Romans in Scotland: life on the frontier

News Story

The Roman occupation of Scotland was dominated by the military. There were no civilian towns or country villas. But the forts were not just military bases. They became the heart of communities.

Life on the Frontier

Civilians travelled with the unit, as did families of the troops, shopkeepers and traders who would take advantage of the soldiers' wages, and craftworkers producing items for the needs of the garrison and community. This was not a purely male environment. Finds such as different-sized shoes show that women and children lived around these frontier forts as well.

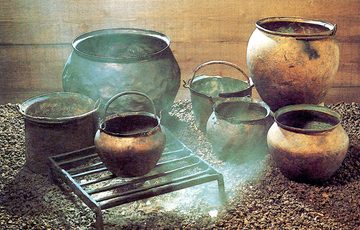

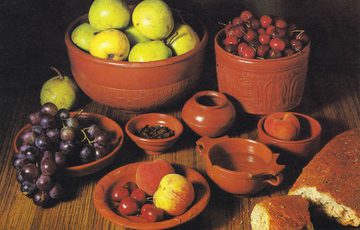

There was a strict hierarchy within the army. The commanding officer and his family lived a life of relative luxury, waited on by enslaved people who cooked their food and served their meals in fine crockery. The soldiers had to cook their own food communally with their mess-mates. The everyday pots of the soldiers were very different from the exotic imported dishes of the officers.

In off-duty times, soldiers would go to the bathhouse. Every fort would have one, to relax, gossip and gamble in. The settlements which sprang up around the fort included pubs and fast-food joints serving the soldiers’ needs. Like a garrison town today, the army was the focus of life for a much wider community.

Image gallery

These soldiers were more than just fighting men. Many had other skills, for instance as craft-workers. Most units would have a doctor within their ranks, armed with a selection of stomach-turning medical implements.

In off-duty times, soldiers would go to the bathhouse to relax, gossip and gamble. The settlements which sprung up around the fort included pubs and fast-food joints serving the soldiers’ needs. Like a garrison town today, the army was the focus of life for a much wider community.

Religion on the frontier

In the Roman world, your fate was at the mercy of the gods and they could be cruel. A careful person would honour them, giving gifts in return for their protection and favour. Roman religion worked on a contract basis: you asked a particular god for help in some matter and, if there was a positive outcome, you fulfilled your vow by making an offering or putting up an altar to them.

Image gallery

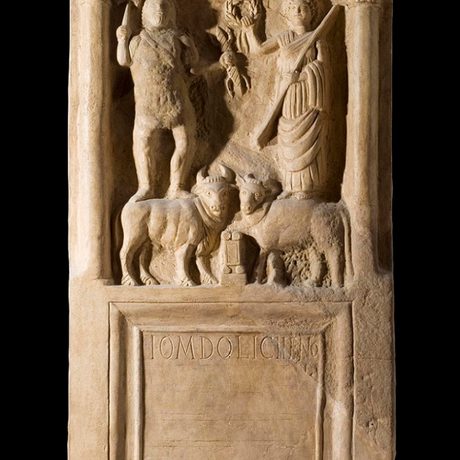

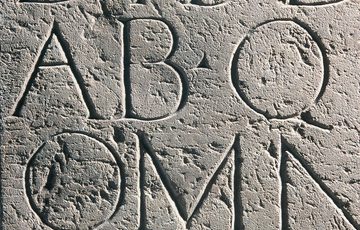

The frontier was a world of many gods, all with different powers. Many of them came from the heart of the Empire, such as Jupiter, king of the gods, or Mercury, who protected travellers and merchants. The garrison held regular ceremonies to Jupiter and the emperor, to show its loyalty. Animals were sacrificed and offerings poured onto altars that recorded these generous acts.

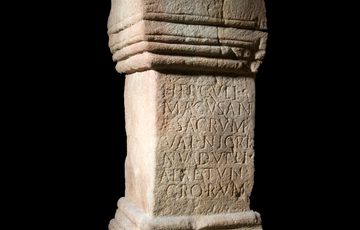

Gods from their homelands also travelled with the troops. Inscriptions record deities from the lower Rhine such as Ricagambeda. Sometimes local gods were linked to Roman ones, such as Hercules Magusanus, chief god of the Batavians and the Tungrians.

The soldiers were also careful not to offend local gods. Offerings were made to them too, and local deities were taken over into the Roman world. One example is Brigantia, a northern English tribal goddess who was turned into a very Roman deity indeed, with wings and armour. The Roman world was a cosmopolitan one, and beliefs travelled all around the Empire. Gods from the far end of the Empire became popular with the soldiers, such as Jupiter Dolichenus, from Syria, and Mithras, ultimately from Persia.

Gods were not just honoured with altars. They were shown in decoration, on pots, vehicle fittings and armour. Your finger ring would be decorated with a gemstone of a particular god, carrying them with you for protection. The frontier was a medley of different deities.

Links to the locals

When the Romans occupied your land, your options were limited. You could fight this all-powerful army, you could flee beyond their reach, or you could find a way to deal with them. People two thousand years ago used all three options.

The Romans realised they could not fight everyone. If you chose to deal with Rome, there were benefits. Groups who were willing to co-operate were more likely to be left untroubled. The Romans dealt with the leaders and relied on them to keep their followers in check. From this, leaders got access to desirable items of Roman culture.

Far from taking anything on offer, however, they chose things that were useful to them: not togas and baths, but brooches and feasting gear, such as fine pottery and glass vessels. These were things that could be used to impress people in local society.

This was an unstable and fast-changing world, as Rome’s priorities changed and different local leaders took different decisions. One generation’s friend could be the next generation’s enemy.

The Romans pulled back to Hadrian’s Wall in the late 2nd century. They left a country in turmoil, with serious attacks targeting the Roman frontier. The Romans fought back, but also built links to some leaders using gifts of silver coins. ‘Frontier diplomacy’ involved giving gifts to friendly groups and trying to create tensions within local society by favouring some people over others. The great hoard of hacked silver from Traprain Law (East Lothian), which was buried in the 5th century, represents gifts from the Roman world over several generations.

The Romans may have come into Scotland with the intention of conquest, but as Britannia came to an end they were reliant on diplomacy, not military might, to keep the frontier secure.