Collections data

On this page

Introduction

Data associated with insect specimens is no less important than the specimens themselves and, arguably, is used more often. Curators, researchers, and the public benefit when data is available and accessible.

What data is most important?

When it comes to entomology collections, it is vital to have a unique identifier for each specimen and to know the three "W”s:

- what (taxonomic name of the specimen)

- where (locality where it was found and storage location)

- when (the date of collection)

Who (collector or donor) and how (acquisition details, collection permits, and other associated information) are also very helpful. Images of specimens are part of the data too.

Types of collection data

Data for entomology collections can include different types of information.

Data about the collection

Data about the collection may include acquisition records or details about distinct parts of the collection (for example British flies, Sumatran butterflies or the collection of Baron de Worms).

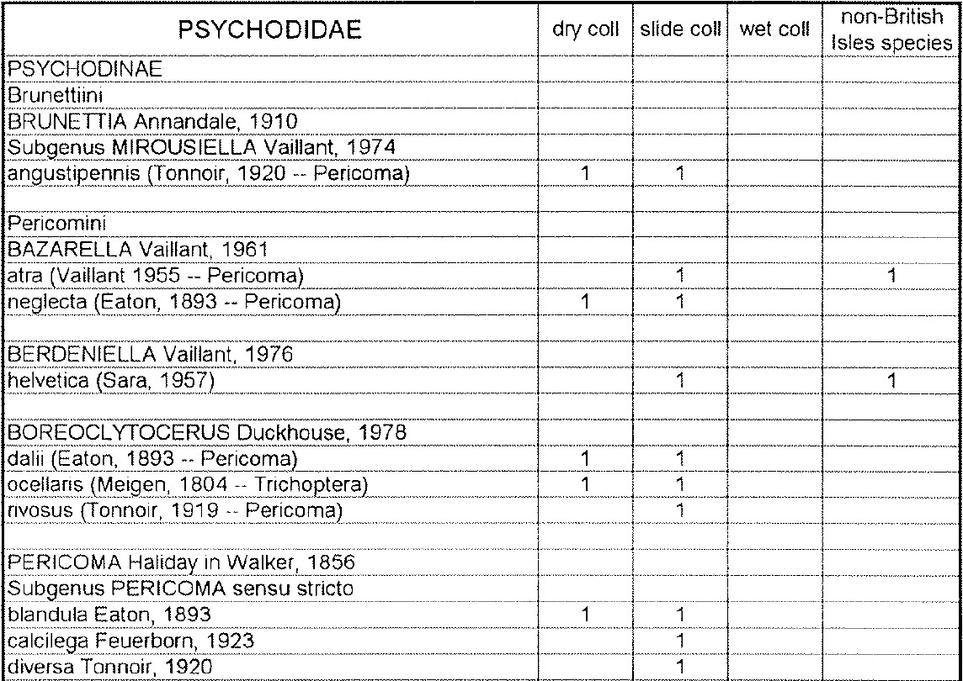

Taxonomy data

Taxonomy data includes information such as number of specimens and storage locations (as entomology collections are normally arranged taxonomically). This data may be in the form of catalogues, lists of taxa held, or indices.

Specimen data

Specimen data includes where, when, and under what circumstances a specimen was collected and acquired by the collection. This data is most often on the specimen label but may also be found in old registers or field notebooks.

Formats of collection data

Data for entomology collections can be found in three main formats:

- analogue- the physical specimen label or other physical objects like manuscripts, books, and catalogues (you can read more about labelling in Specimen Preparation and Conservation)

- digital- digital files containing searchable text, such as spreadsheets and databases

- hybrid- digital files not containing textual information, such as images of labels or registers

Only digital data can be used and shared with ease. That is why we will focus on digital data in the rest of this training.

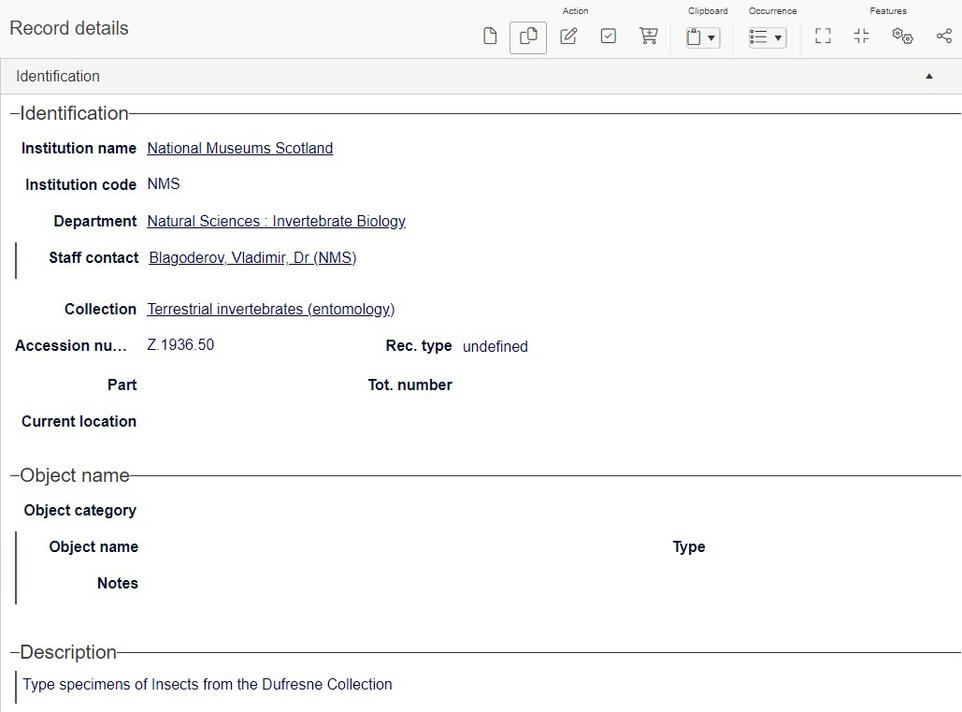

Data management software

Digital data can be stored and managed in a variety of formats and software, including:

- Plain text files

- Spreadsheets

- Collection management systems (CMS)

Plain text files

Plain text files are the simplest way to manage digital data. Text files allow you to retrieve information by searching for a string of characters. However, it’s very difficult to maintain data integrity and structure or to analyse data.

Spreadsheets

Spreadsheets can be a very useful tool and are used widely to collect and exchange data. It is possible to structure data, and search, filter and analyse records. However, data presentation and integrity capabilities are limited.

Collection management systems

Collection management systems (CMS) are mostly built as relational databases and can perform most, if not all, functions necessary in collection management. There are a great number of CMSs suitable for natural history collections. They can be:

- Commercial: EMu, Axiell Collections (formerly AdLib), and others

- Open-source or community-supported: Symbiota, Arctos

- In-house developed: PAPIS, Kotka, DaRWIN

- Subscription/support based: EarthCape, Specify

Whatever data management software is used, it is imperative to follow accepted data standards and to structure data in a way that they can be easily queried, manipulated, and shared. Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG) has developed Darwin Core and World Geographical Scheme to help with this.

Digitisation

Digitisation means translating data from analogue to digital format. It is one of the most important tasks in collection management. It can be an expensive and laborious project but saves time and effort in the long run.

Digitisation can be done to different levels, but once a level is chosen it is crucial to be consistent and maintain this level of digitisation through the entire project.

At the minimum level, digitisation must include the following information for each specimen:

- unique ID

- taxonomy

- location in the collection

- a transcription of the physical label

Enhanced levels of digitisation may include:

- verbatim and interpreted locality

- georeferencing information

- associated data

- images

Unique ID

A unique identifier (uID) is a combination of letters and numbers that uniquely identifies every specimen in the collection. Every specimen must be assigned a uID that is unique to that specimen. The uID is assigned during the registration process, either by software or manually.

In many cases, particularly when acquiring a big insect collection, curators and registrars will register entire collections under one registration number (e.g. NMSZ.2019.29). They then add an additional number for every specimen, to make the string unique for each specimen (NMSZ.2019.29.17).

It can be difficult to avoid duplicate numbers when assigning uIDs manually. If possible, use continuing numbering to ensure each number is used only once (NMS-000000001 to NMS-999999999). This format also means the data can be sorted properly by spreadsheets and databases.

A label with the uID should be printed and added to the corresponding specimen (as pictured).

A uID can also be encoded as a barcode and printed as a barcode label. Two-dimensional DataMatrix and QR barcodes are the most used formats in entomological collections. It is best practice to print the alphanumeric version of the uID next to the barcode. This way the label will be both human- and machine-readable. See the iDigBio Specimen Barcode and Labeling Guide for more information.

Universally Unique Identifiers (UUID or GUID) are the safest way to ensure that uIDs are unique. They are widely used in software, including CMS. However, because of the length of the string (32 characters) they’re not very user-friendly and not always practicable for labels.

Taxonomy

Recording accurate biological taxonomy information can be challenging for entomological collections. There are vast numbers of species, even just in the UK. Curators are not always experts in insects, and never in all insects. Names for species recorded in the collection may be incorrect or outdated.

Fortunately, the UK has one of the best studied faunas in the world, and modern catalogues and checklists have been published for all major groups. Consult these resources to help you accurately record species in your collection:

- The Natural History Museum maintains UK Species Inventory

- British Isles checklists are regularly published and updated for major groups, such as Coleoptera (beetles), Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), Diptera (flies), and Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, sawflies and ants)

- Taxonomies can also be found on Catalogue of Life and Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) websites

If a specimen is re-identified, it is important to:

- preserve the previous identification history

- record the new taxonomic name

- record who re-identified the specimen

- record the date when it was re-identified

Location

Record the location of the specimen in the collection and update the location any time the specimen is moved.

Location can be recorded as absolute (room, aisle, cabinet, drawer/box) or relative (taxonomic series). In the latter case a distinct taxonomic unit, for example a family, is assigned a number or a string. If another drawer or a cabinet is added to a series it does not affect all other series, and they do not have to be updated.

Label transcription

It is important to transcribe the physical data labels of each specimen when digitising a collection. To do this, you usually need to remove the labels from the specimen pin. You can then photograph the labels and transcribe from these images.

Transcribing data labels can be difficult. These are some of the problems you might come across.

Incomplete data

Sometimes labels have incomplete data, particularly in terms of locality (where the insect was collected).

The locality of the specimen should be recorded as completely as possible, in increasing order of precision (for example, country, state or county, major area, minor area, exact locality, coordinates). However, often this was not done with older specimens.

In these cases, when a locality cannot be identified with certainty,[GW1] you will need to do some detective work. For example, you may have to use old maps, gazetteers, or even newspapers to find how the place names changed through times.

Overall, when digitising labels it is best practice to record locality information in two ways: verbatim (as it occurs on the label or in the ledger or field notebook) and interpreted (complete locality information separated into fields such as country, state or county, and so on).

Blog post has been removed [GW1]

Disassociated data

Collectors in the past often recorded complete collecting data in catalogues or ledgers and put only a number or placeholder on the specimen label. In these cases, the data is at risk of being disassociated with the label.

When digitising, it is best practice to transcribe the ledgers and match the specimens with the corresponding records. This may take more time but makes the data much easier to use and share in the long run.

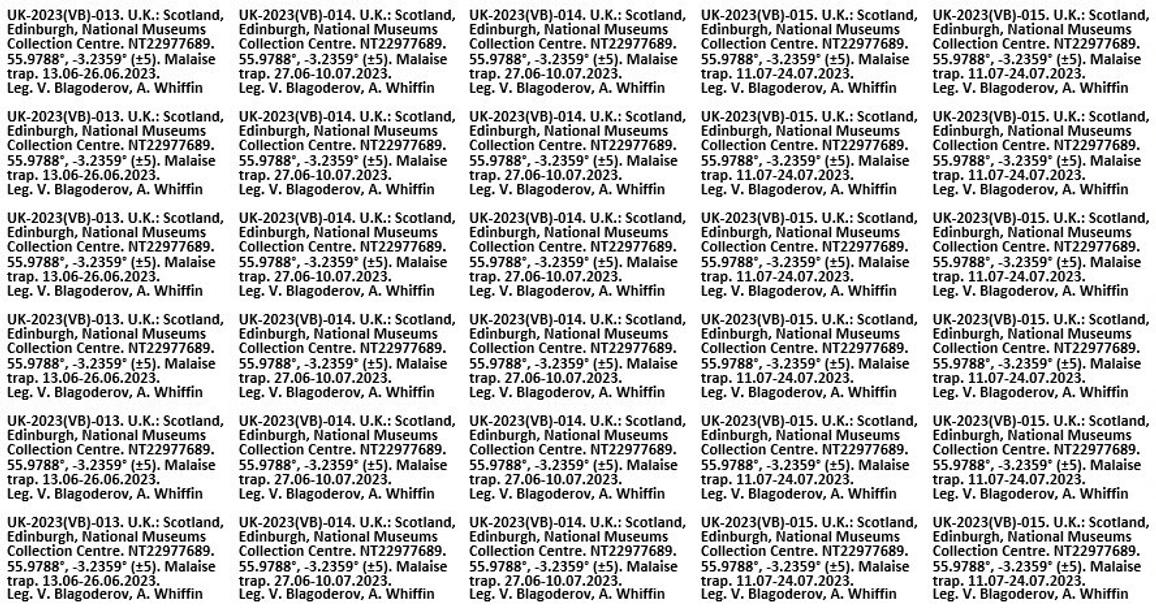

Temporary labels

During collecting, specimens are often given a temporary field label. These labels usually have incomplete or abbreviated information, with more accurate data often recorded in the field notebooks.

Temporary labels should be replaced with proper labels immediately after collecting, but this does not always happen. This is a problem because if we lose knowledge about where and when the insect was collected, the scientific value of the specimen is very limited.

Avoid accepting donations of specimen collections that are not properly labelled, or ensure temporary labels are replaced with permanent labels before formal acquisition.

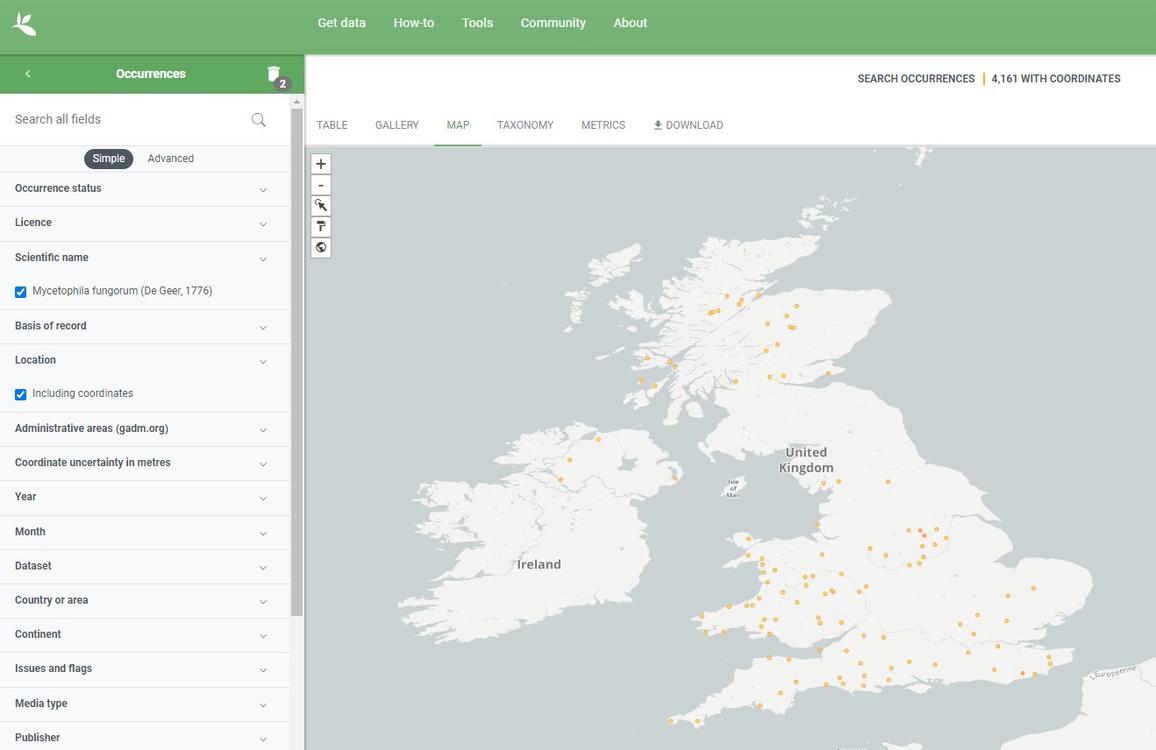

Georeferencing

Georeferencing involves calculating geographic coordinates for a locality, so we can accurately find on a map where the insect was collected.

During digitisation it is best practice, where possible, to calculate and add coordinates for specimens that do not have this data. For more detailed guidance on georeferencing, refer to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF):

OS Grid Reference is most commonly used in UK, but it has to be converted to coordinates if the data is to be published with aggregators such as GBIF. The most common and useful coordinate format is decimal degrees.

Born-digital data

When collecting insects nowadays, it is best practice, if possible, to create data in digital form right in the field. We can do this using digital pens and tablets, along with platforms such as Epicollect5. This helps to avoid complications with digitisation and speeds up labelling and databasing of specimens.

Data mobilisation and publication

To be useful, digitised data must be published. This can be done through:

- aggregators such as National Biodiversity Network or Global Biodiversity Information Facility

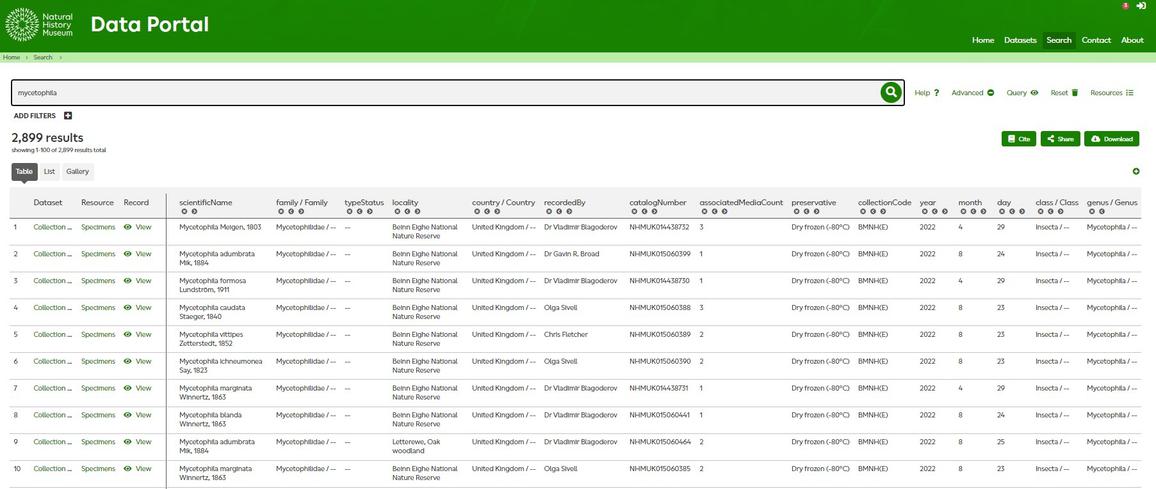

- directly through a dedicated institutional data portal, such as the Natural History Museum data portal

- other data publishers, such as Zenodo

Additional resources

- UK Grid Reference Finder

- Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland – Grid-square map, vice-county and summary taxon list tool

- iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections) and Wiki

- EntomoLabels provides software for designing and printing insect labels. The website may ask you to allow notifications to verify you are not a robot. We advise you do not allow notifications and select Block. Make your labels now

Header image credit: Duncan McGlynn.

More in this resource

Why do museums collect insects?

Learn why we collect insects, and what they’re used for.

Preservation and storage methods

As insects are so diverse in their form, there are many ways they can be preserved.

Identifying pests and managing infestations

Discover how to identify pests, and manage infestations.

Specimen preparation and conservation

Discover how to prepare and conserve specimens.