A watch for King James VI and I's favourite

News Story

In around 1615, James VI and I presented his favourite courtier, Robert Kerr, Earl of Somerset, with an elaborate pendant watch. Within a year, Kerr had spectacularly fallen from grace and had been replaced in the king’s affections by George Villiers, the future Duke of Buckingham.

Close up of 17th century silver watch with six dials and apertures. Museum reference H.NL 63.

This finely engraved watch tells the story of three Scotsmen who moved to London, following the succession of James VI in 1603 to Elizabeth I’s thrones of England and Ireland. Its Scottish maker, David Ramsay, its recipient, the Earl of Somerset, and the royal patron, now James VI and I, had all been born in Scotland, but their fortunes were transformed by the opportunities afforded by James’s new court at Whitehall in London.

An impressive gift

The silver and gilt watch face and its brass mechanism are enclosed in a finely engraved case made from silver. On its outer sides are depicted two biblical scenes from John, chapter 13: The Last Supper, and Jesus washing Simon Peter's feet. On one inner side is a portrait of James VI and I with his wife Anna of Denmark, in full court dress. The other side shows the coat of arms of Robert Kerr, Earl of Somerset.

The watch has a small ring at its top. Through this, the watch could be suspended from a ribbon or chain around the wearer’s neck or attached to clothing. It has six dials and apertures from which you can tell the time to within half an hour, the day of the week and month, the name of the month and its main zodiac sign, and the phase of the moon. Since you had to open the watchcase to see the dials, reading the time was intended to be quite a performance, especially with such a fine watch. It was intended to impress all who saw it.

Close of up 17th century Ramsay-Kerr silver watch's engraved case made from silver. Museum reference H.NL 63.

The king's favourite

Robert Kerr (c. 1585 – 1645) was one of the sons of Thomas Kerr, the Laird of Ferniehirst, near Jedburgh in the Scottish Borders. As a younger son, he would not inherit the family’s lands and was expected to make his fortunes elsewhere. He secured the patronage of a powerful fellow borderer, George Home, subsequently the Earl of Dunbar.

When James VI took up residence at Whitehall, it was likely Dunbar who secured the young Robert Kerr a place in James’s household as a groom of the Bedchamber. The Bedchamber was one of two formal rooms at court through which access to the king was controlled. This position put Kerr frequently in the royal presence and by 1610 he was widely known as the king’s favourite.

Kerr was reputedly not very bright, his handwriting was terrible, and his knowledge of Latin was poor. But his redeeming features were his very good looks, and his courtly skills including dancing. It is likely also that his knowledge of Scots (as opposed to English) and his Scottish accent would have been comfortingly familiar to a king far from his original home.

Portrait of Robert Carr by Nicholas Hilliard, circa 1611.

James VI and I's intense affection

While the precise nature of their relationship is uncertain, it was intensely felt. This affection was manifested in the significant gifts that Kerr received from James of lands, offices and money. In 1611 the king created Kerr Viscount Rochester, and installed him as a member of the Order of the Garter, the highest such honour in England. In 1613, he was elevated further to the Earldom of Somerset. To this day, he is widely known as Somerset. Later in the same year, Somerset married the English noblewoman, Frances Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk. As an Earl, Somerset amassed a rich collection of Dutch and Italian paintings, jewellery, gold and silverware, statues and luxurious clothing in a large suite of rooms at Whitehall.

We can see the impact of King James’s love in the creation of the coat of arms for the newly ennobled Kerr that appears on the watchcase. The Kerr family arms (the pointed chevron device with three mullets or stars) were augmented with the royal Stewart lion rampant. But further, in a mark of special favour, the tiny lion passant was added at the king’s request into the top left of the Kerr arms.

The watch’s imagery, however, is complex. Alongside this demonstration of the king’s affection to Somerset, is the marital portrait of James with Anna. The couple are posed in full glory under the British coat of arms. This is a grand statement of James’s kingship of the whole of Great Britain, and of the key embodiment and preservation of it in his marriage to Queen Anna. For James it seems that his love for Somerset could exist alongside that for his wife.

Ramsay-Kerr watchcase with a new coat of arms, featuring the Kerr family arms augmented with the royal Stewart lion rampant. Museum reference H.NL 63.

Ramsay-Kerr watchcase with royal portrait of James VI and Anna in court dress. Museum reference H.NL 63.

A Scotsman Clockmaker

David Ramsay (c. 1575-1660) was brought up in Fife, near St Andrews. In 1594 he was apprenticed to James VI’s royal armourer and learnt the art of gunsmithing and armoury. He travelled extensively to refine his skills in the making of timepieces and knowledge of metals, including to Paris. By 1613, he was named a page of the Bedchamber, and he was also working as a clockmaker to James VI and I. He became Chief Clockmaker at the royal court in 1618, and continued in Charles I’s service, becoming the first Master of the Clockmaker’s Company in England in 1632.

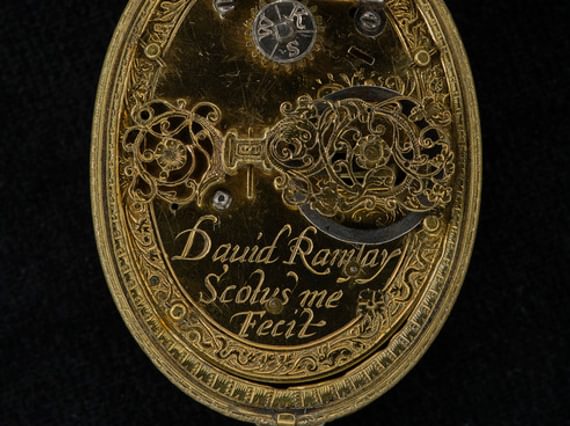

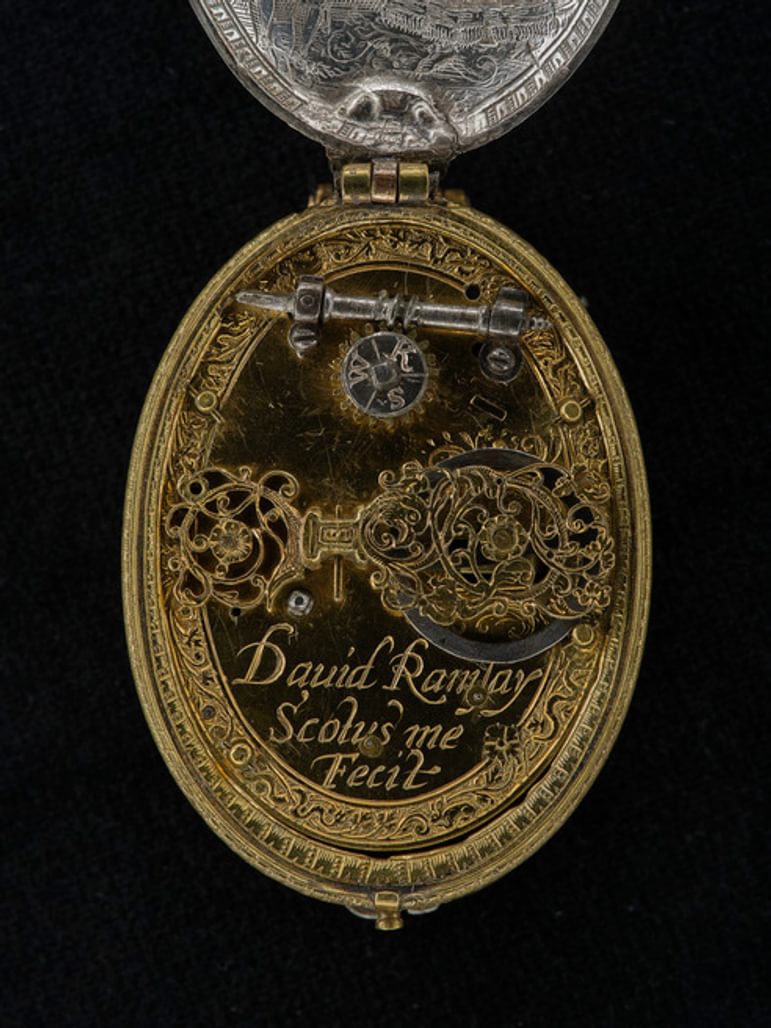

Ramsay was a good example of the many Scotsmen who followed King James to London following the Union of the Crowns in 1603. He established a successful business there where he combined the skills of engravers and watch mechanism-makers to create timepieces. At least 14 of these timepieces still survive. He signed the watch given to Somerset, 'David Ramsay Scotus me fecit' (David Ramsay, Scotsman, made me). It is notable that he preserved his Scottish nationality in this signature of an object made in London for a now British king.

Ramsay-Kerr watchcase signed 'David Ramsay Scotus, me fecit'. Museum reference H.NL 63.

The workings of government

As a senior member of the royal household, Somerset helped to control access to the king. He was able to present requests for offices and titles on behalf of others to James, in return for which he often received monies and favours. This gave him political power among the court factions. King James also gave him governmental power in making him a privy councillor in both England and Scotland and named him Lord Treasurer in Scotland.

These honours worked not only to enrich Somerset, but his wider family too benefitted from lands and offices that he channeled towards them. In this way, the king was able to grease the wheels of local government in the Borders. The Kerr family around Jedburgh was instrumental in carrying out the king’s wishes in the ‘Pacification’ of crime in the cross-border region. In wielding targeted patronage like this, James could continue to govern events in Scotland, even though he was now over 300 miles away.

Somerset's downfall

While Somerset's access to James brought him great power, it also alienated English courtiers from different political factions. This included those who disliked the influence wielded by significant numbers of Scotsmen in the royal household.

At this time Somerset's previously influential ally, Sir Thomas Overbury, was poisoned while held in the Tower of London.

When investigations into Overbury’s murder reopened in 1615, Somerset and his wife Frances were imprisoned and later found guilty. Somerset always denied involvement, and may well have been innocent, but Frances admitted her doings. Although the king eventually pardoned and freed both of them, Somerset never returned to favour.

As quickly and dramatically as Somerset had fallen, George Villiers rose, soon becoming the Marquis then Duke of Buckingham.

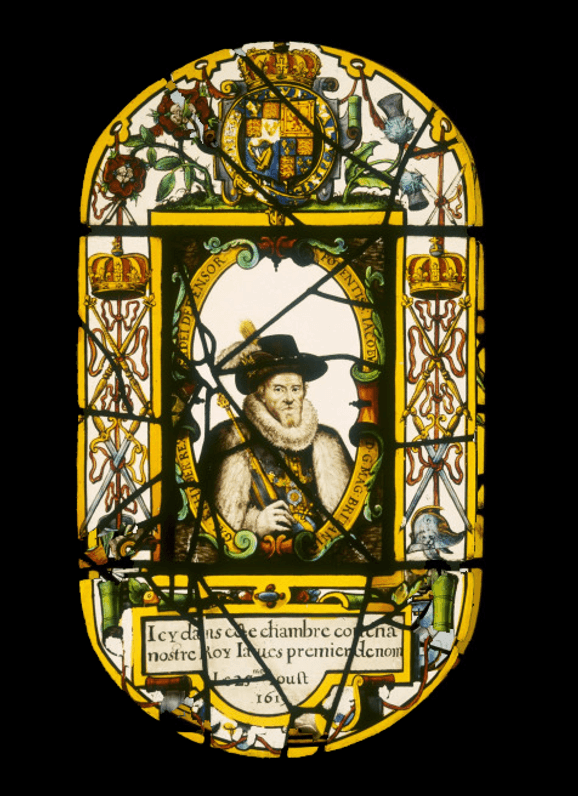

Oval panel of stained and painted glass with a rectangular panel in centre containing a half length portrait of James VI and I, c.1619. Museum reference A.1966.174.

Oval panel of stained and painted glass with a rectangular panel in centre containing a half length portrait of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, c.1619. Museum reference A.1966.175.

Written by

Dr Anna Groundwater

Principal Curator, Renaissance and Early Modern History