The Carnoustie Hoard: A rare glimpse into Bronze Age customs

News Story

Weapons, such as swords and spears, were widely used and buried in Bronze Age Europe around 1000 BC. It is rare, however, to encounter weapons buried at a settlement where people went about their daily lives.

A carefully wrapped sword and spearhead at Carnoustie represent an exceedingly rare exception. Wider archaeological investigations revealed a rich Neolithic and Bronze Age landscape just under the surface…

Found under a football pitch

In 2016, GUARD Archaeology were investigating a site just outside Carnoustie in Angus. The site was due to be developed into two football pitches. Just below the topsoil, glimpses of green corrosion started to appear, a sign that ancient copper or bronze objects had been found. These were the first clues of the bronze weapons and ornaments buried in a pit three thousand years ago. This find is now known as the Carnoustie hoard.

Image gallery

Lifting the Carnoustie Bronze Age Sword during the GUARD Finds Lab excavation.

Excavating the Carnoustie Bronze Age Hoard in the GUARD Finds Lab.

Excavating the Carnoustie Bronze Age Hoard in the GUARD Finds Lab

The hoard was wrapped in plaster and 'block lifted' from the ground. This is an archaeological conservation technique that involves excavating the hoard out of the ground as a block. This then allows the block to be x-rayed, followed by careful excavation under laboratory conditions.

The hoard was excavated by an archaeologist and conservator. Together, they uncovered the bronze weapons, as well as rare organic wrappings.

What’s in the hoard?

The hoard contained a bronze sword in a scabbard wrapped in a woven wool garment or textile, fastened by a pin. Alongside this was a bronze spearhead. Its blade was wrapped in sheepskin and its socket wrapped in a fine woollen cloth. The preservation conditions allow us to glimpse an exceptional level of information. We can glean details on how these objects were made and how this hoard was formed.

A Bronze Age sword, part of the Carnoustie Hoard.

The bronze sword is complete, with the remains of a wooden or horn handle, as well as an unusual lead-tin pommel. It was buried in a wooden scabbard made from strips of hazel wood, which had a bronze chape (a fitting for the end of the scabbard). A bronze mount or fitting may have been decoration for the scabbard or for attaching it to a belt.

The large spearhead has a highly decorative gold collar around its socket. It would have been hafted onto a long wooden spear shaft, though no evidence for this was present in the pit. The gold socket collar is particularly special. Herringbone decoration and lines have been incised or cast into the bronze socket and then gold has been applied as a foil.

This represents an exquisite piece of craft. The gold collar marks this spearhead as particularly special as it is one of only five known from Britain and Ireland. The only other example from Scotland was found as part of another hoard, at Pyotdykes, just 20km to the west, though dating slightly later. Perhaps there was some generational link between the two owners?

Image gallery

Bronze Age spearhead found as part of the Carnoustie Hoard.

Bronze Age spearhead from the Pyotdykes hoard.

The bronze pin is a form known as a ‘disc-headed pin’. This is characterised by a circular disc head with concentric circles as decoration and a long shank. Woven textile found with the pin indicates that the pin had probably been used to secure the bundle containing the sword.

This starts to build a well-rounded picture of the burial of the hoard. The sword in its scabbard carefully wrapped, secured with a pin and placed in a shallow pit. The spearhead wrapped separately and laid down beside it.

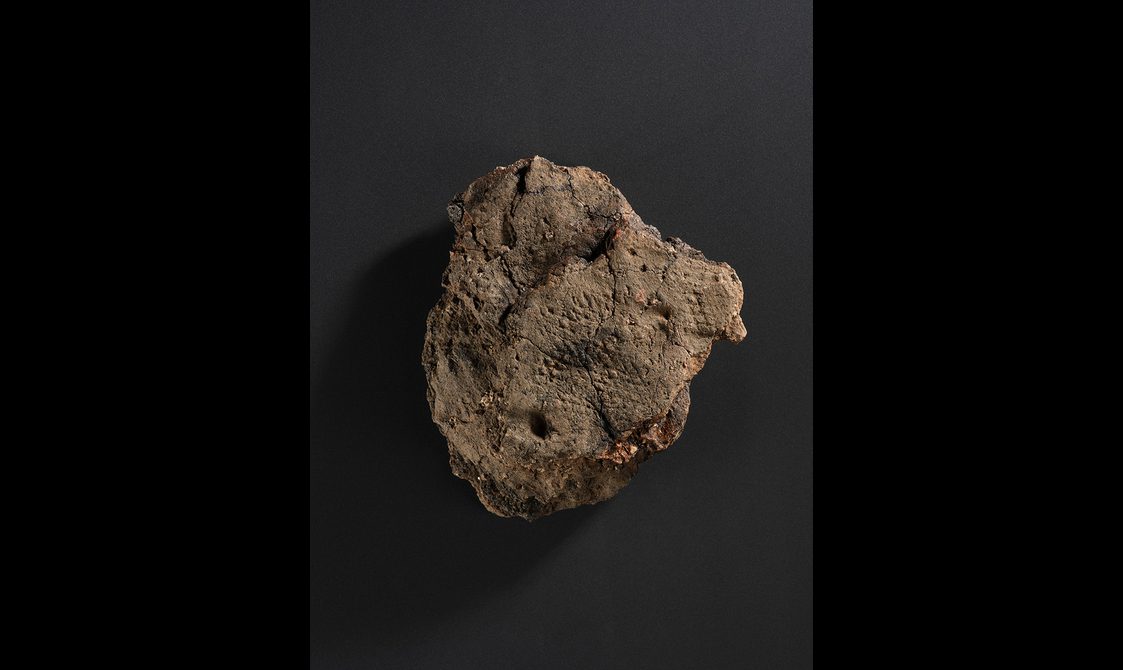

Some mysteries remain though. A small organic piece, affectionately known as ‘The Biscuit’, is just over 30mm long and has an unusual shape. It was found near the sword hilt and is probably incomplete. It was perhaps once part of a strap.

A disc-headed pin, part of the Carnoustie Hoard.

A fragment of unidentified organic matter known as 'the Biscuit' from the Carnoustie Hoard.

Dating the hoard

The metal objects in the hoard allow us to date it to the Late Bronze Age, c.1150–800 BC, but the organic material helps us refine this. Using the scabbard wood, archaeologists were able to date the hoard to 1120–920 cal BC. This is a period when weapons were being buried across Britain.

The remains of a wooden scabbard made from strips of hazel wood. Part of the Carnoustie Hoard.

Where was the hoard buried?

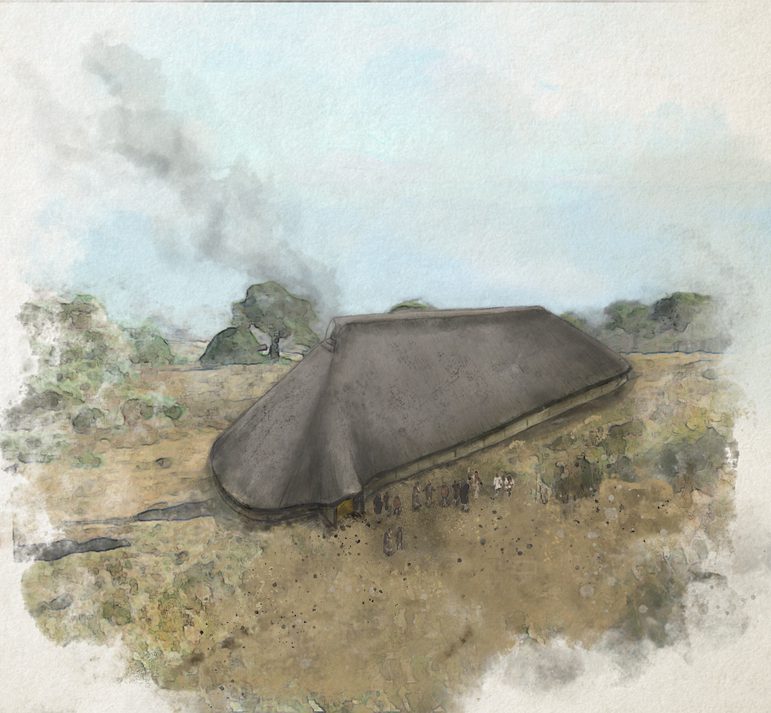

The hoard wasn’t the only thing found during excavation. Archaeologists uncovered the remains of multiple buildings, and groups of pits. Several were used during the Late Bronze Age. Three round structures (named 5, 6 and 14) were constructed by arcs of inner and outer timber posts with wattle and daub panels forming the outer wall. They would have had thatched or turfed conical roofs. The largest, Structure 6, may have been up to 15m in diameter. Each structure had a ‘porch’ at its entrance, which faced south-east.

Excavation of the floor of one of the buildings (Structure 5) uncovered materials indicating that it was once inhabited. These included stone tools, a spindle whorl, pottery and a broken cannel coal or shale bracelet. The hoard was buried in a pit just to the north of Bronze Age Structure 5. Radiocarbon dates suggest the hoard may have been deposited while the house was in use.

Bronze Age hoards are usually buried in the landscape, such as on hills or in water. They are rarely found near settled areas. This makes the discovery of the Carnoustie hoard and its proximity to one or more structures, particularly important. Did the people who owned and buried the hoard live in these structures?

Neolithic origins

The Late Bronze Age habitation of the area was just the latest in a long history of interactions at the site. Over a thousand years earlier, during the Early Bronze Age (c.2500-2000 BC), the area was used as a burial ground. Cremated human remains and pottery were buried here. And 1500 years before that a large timber hall was erected.

Pottery, stone tools and a shale bangle fragment from the Late Bronze Age structure near the Carnoustie Hoard.

In the early fourth millennium BC, around 3960 BC, large oak timbers were erected in load-bearing pits and postholes to create a building. The structure (structure 8) was about 34.5 metres long (longer than three double-decker buses) and about 8.6 metres wide. It enclosed a massive space, with fragments of lithics, stone tools and pottery deposited in the pits.

Reconstruction of the Structure 8 Neolithic long timber hall at Carnoustie.

This large building required an enormous communal and collective effort and organisation. Such buildings, known as timber halls, have been found elsewhere in Scotland. They are often viewed as monuments and places for social gatherings. A second timber hall was built around the same time as the first hall, which was also large at nearly 20 metres long.

As archaeologist Beverley Ballin-Smith puts it:

These important buildings probably had multiple functions predicated on bringing together people from different communities or the wider locale to share common rituals and traditions at specific times of the year.

Beverley Ballin-Smith, GUARD Archaeology Ltd

The timber halls were in use for about 200–300 years until a new, smaller timber building was constructed. The newer structure reused some of the same original features of the first timber hall, such as the entrance. This new building was 14 metres long. It clearly represented some generational continuity for the communities living at the site.

Again, lithics, stone tools and pottery were buried in pits and postholes, as well as polishers and fragments of querns. A particularly intriguing deposit is a polished stone axehead. This axehead may never have been used.

This smaller hall, too, fell out of use over time. But there is continued evidence for people at the site over the following centuries. The later settlement and hoard deposition at Carnoustie was thus part of a much longer engagement with the site.

Image gallery

Reconstruction of Structure 8 Neolithic small timber hall at Carnoustie.

Neolithic stone axehead from a timber hall at Carnoustie.

Textile impression on the base of a Neolithic pot at Carnoustie.

Neolithic Grooved Ware pottery from Carnoustie.

Weapons in the Bronze Age

Returning to the hoard, we can think about what the objects tell us about wider society during the Late Bronze Age. Analysis of the sword shows that it had been used in combat. Bronze swords were deadly weapons. They were part of a repertoire of weapons and equipment used and worn by people to defend their homes and undertake raids. Owning and using a sword was also a sign of status.

Similarly, the Carnoustie spearhead would have been a rare object, a symbol of elite craft and prestige. The decorated gold collar set it apart from other spears in use at the time. The spear, however, shows no obvious sign of use and was buried without a shaft. Perhaps this object was purely ceremonial, never intended for combat.

Many swords and spears do show signs of use. Conflict between individuals and communities must have occurred regularly over this period. However, the main reason we know of these weapons is because swords and spears, both used and unused, were commonly buried during the Late Bronze Age.

Some, like Carnoustie, were left complete. The Peebles Hoard in the Scottish Borders contained a complete sword in a scabbard. This was laid on top of a wide array of remarkable fittings and horse equipment. Occasionally weapons were placed in rivers or gathered and sunk into bogs. Three swords found on the Isle of Shuna were thrust in tip down into a bog.

At Duddingston Loch, Edinburgh, around 40-50 swords and spears were placed on a pyre and destroyed through fire. This perhaps represented the aftermath of a conflict and the destruction of enemy weapons. Nearer to Carnoustie, at Pyotdykes, two complete swords were buried - one still in its scabbard. Alongside the swords, another spearhead with gold decoration was also found. A small plug of woven nettle-fibre or flax fabric was found in the spearhead socket.

The Carnoustie community

The Carnoustie hoard allows us to construct rich and intimate stories about how the objects were buried and by whom. This is thanks to the careful excavation of the hoard and the surrounding area. The amazing preservation of the organic materials enables us to conduct research to help uncover its secrets.

Around three thousand years ago, a family or community gathered outside their house. They lived in a landscape already rich with archaeological heritage. They carefully wrapped a treasured sword in its scabbard – a sword that had seen battle – as well as a prized spearhead, a symbol of elite status.

The sword bundle was fastened with a beautiful dress pin. The spearhead blade was carefully wrapped in sheepskin, while the delicate gold socket was wrapped in woollen cloth. A pit was dug, and the objects were laid carefully, probably as part of a public ceremony. Perhaps for future safekeeping or an act of remembrance. They reflect the thoughts and ideologies of the Bronze Age people. These objects lay here for three thousand years, waiting to be uncovered and for their stories to be told.

The Carnoustie Hoard will be displayed part of Scotland's First Warriors at the National Museum of Scotland in 2026.