The Darien Scheme: Scotland's failed venture to colonise part of Panama

News Story

This imposing iron chest stored money and documents associated with the Company of Scotland. This was a trading company set up in 1695 to promote Scottish trade overseas.

The company is now remembered for the disastrous venture to establish a trading colony in the Isthmus of Darien, in today’s Guna Yala region of Panama, in 1698. This failure cost 2,000 lives and lost Scotland a quarter of its liquid capital. Such a huge loss of capital helped push Scotland towards an incorporating union with England.

Darien Chest c.1695. Museum reference K.2000.368.

The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies

The late 17th century was a difficult economic period for Scotland. While trade with England had increased since the 1600s, the 1661 English Navigation Act barred Scottish ships from trading in English ports overseas. Scotland was unable to benefit from the trading links and colonies established by the English in the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

In response, the Parliament of Scotland enacted several economic remedies in 1695. This included the foundation of the Bank of Scotland. Then, on 26 June, the ‘Act for a company trading to Africa and the Indies’ established the Company of Scotland to conduct overseas trade and set up trading posts, colonies, and plantations abroad. The Company received legal privileges to protect trade in the ports it founded. It could also negotiate 'treaties of peace and commerce' with indigenous rulers in Asia, Africa, and America. This was intended to be a Scottish equivalent of the East India Trading Company set up by the English almost a century before.

The company was to be financed by public subscription of at least £100 per stockholder and no more than £3,000. Further acts ‘for the encouragement of the undertakers for foreign trade’ allowed, for instance, burghs to invest their capital held for the common good in the company. This was significant. It encouraged widespread and large investment from Scottish landed and merchant elites. Potentially, it also left many people vulnerable to any financial downturn.

The Darien Scheme

The Company of Scotland attempted expansion through involvement with the Darien Scheme. This was an ambitious plan, devised by William Patterson, to develop a colony on the Isthmus of Panama.

Patterson was a merchant and a banker from Dumfriesshire, operating in the West Indies, Edinburgh, and London where he co-founded the Bank of England. From the 1680s he had become convinced of the merits of the Darien Scheme to found a colony in Panama. He hoped to establish a trade route through to the Far East, and thus avoid the treacherous journey around Cape Horn.

Patterson was instrumental in persuading the Scottish government and the Company of Scotland to finance the Darien colony, and he himself accompanied the expedition on which his wife and child died. He survived.

First expedition

There were five ships in the first expedition . The Caledonia, St. Andrew, Unicorn, Dolphin, and Snow set sail from Leith on 14 July 1698. The fleet finally made landfall on 2 November 1698, carrying out their orders to:

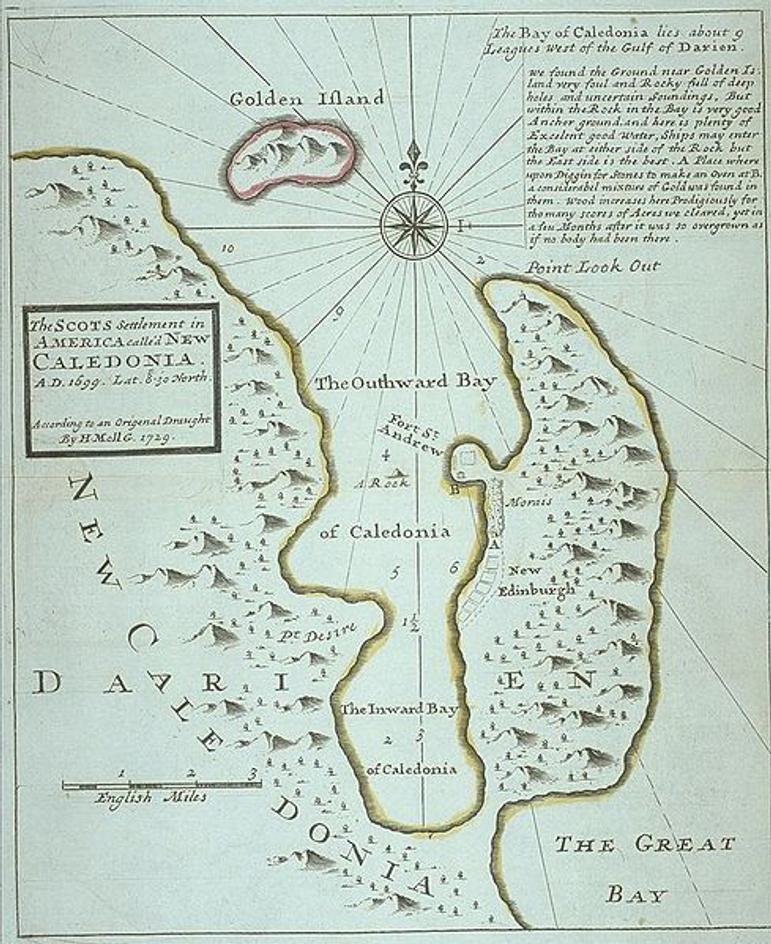

'proceed to the Bay of Darien and make the Isle called the Golden Island … some few leagues to the leeward of the mouth of the great River of Darien … and there make a settlement on the mainland.'

Map of New Caledonia in Darien.

The settlers constructed Fort St Andrew as the main defence. They built a warehouse and huts and named the main settlement New Edinburgh, but agriculture proved difficult. The local Cuna communities, although mostly friendly, refused to buy combs and trinkets offered by the colonists. They also rejected the trade goods of linen, stockings, and shoes. The ships had been laden with these items as trade for provisions in Jamaica and Antigua.

Insufficient food, and the onset of stifling summer heat the following year, exacerbated ill health among the settlers. This led to many deaths. The colony was abandoned, after barely eight months, in July 1699. Only 300 of the 1,200 settlers survived and only one ship managed to return to Scotland.

Second expedition

A second expedition left before word of the disastrous first expedition reached Scotland. There were more than 1,000 people on this voyage, which arrived on 30 November 1699. They found the settlement of New Edinburgh abandoned, deserted, and overgrown. A fear of the Spaniards driving them out led the Scots to attack the Spanish fort at Toubacanti in January 1700. After a month of sustained attacks at Fort St Andrew the Scots surrendered to the Spaniards. They were then permitted to leave. 2,500 settlers had set off from Scotland but only a few hundred survived.

Colonial contexts, and connections to the slave trade

The Darien venture was explicitly part of an attempt by Scottish landed and merchant elites to establish a Scottish version of the burgeoning English colonies overseas. It was an exercise in empire-building. The Company of Scotland was expressly set up to ‘plant colonies, build cities, towns or forts’ and to provide them with the fortified defences they would need. Darien would be the first settlement in ‘New Caledonia’ and its fort called St Andrew after Scotland’s patron saint. When negotiating with indigenous rulers it was to claim the rights to:

‘all manner of treasures, wealth, riches, profits, mines, minerals, fishings, with the whole product and benefit … together with the right of government and admiralty thereof.'

Subsequent plans envisaged Scottish ships involved in a circulatory trade route. This would take them to the west coast of Africa, across the Atlantic to the West Indies, and then, in the case of the Darien Scheme, to Panama. They would return to Europe, or potentially trade across the Pacific to Asia.

There is no mention of a human cargo in the related parliamentary or Company of Scotland statutes, but it is implicit in the orders for sailing. An official Darien colony commission to two Jamaican captains explicitly mentions slavery. The captains were involved with the rescue of the Scottish ship 'Dolphin' from Spanish hands in Cartagena. The commission enumerated six enslaved people as compensation in the event of any hurt sustained during their voyages. Jamaica's usefulness to the Company's slave trade is also mentioned twice in proposals drawn up by two enterprising Jamaicans to improve the fortunes of the Company's colony and trade.

The coat of arms designed for the Company is also telling. It depicts the shield supported by the figures of an indigenous American, and a black African. The Company used this on its seal to mark official regulations and transactions.

It was also used on medals commemorating the founding of the Company and its Darien venture. One example is the silver-gilt medal presented to Colonel Campbell of Finat, for the storming of the Spanish Fort Toubacanti in 1700 as part of the attempt to recover the Scottish position at Darien.

Silver-gilt commemorative medal of the Company of Scotland on the storming of Toubacanti during the Darien venture, medal by Martin Smeltzing, 1700. Front view. Museum reference H.1949.1097.

Silver-gilt commemorative medal of the Company of Scotland on the storming of Toubacanti during the Darien venture, medal by Martin Smeltzing, 1700. Reverse view. Museum reference H.1949.1097.

Colonial rivalry

The Scottish venture was perceived to threaten Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and English colonial and mercantile interests in the region. This included the lucrative trade in enslaved people.

The Panamanian Isthmus was home to white owners and managers using enslaved labour in the goldmines. It was also home to formerly enslaved people, known as Cimarrones, avoiding recapture. The Spanish colonial authorities feared they might join with the Scottish against them. The Scottish were also negotiating with the various indigenous local Cuna communities. Spanish fears were realised in an agreement of mutual protection made between the Council of Caledonia and some of the Cuna leaders in early 1699 which was anti-Spanish in nature.

This picture of colonial rivalry in the West Indies and Central America was further complicated by the presence of the French in pursuit of their own trading interests. Some ex-buccaneers had integrated with the Cuna, and in 1698 a French vessel lay alongside the five Scottish ships in Caledonia Bay.

Tensions between the Scottish venturers and English colonial settlements, and traders in the West Indies, were also difficult. Despite initial approval of the Company of Scotland by King William III, English ships actively frustrated Scottish attempts to sustain their settlement at Darien, particularly in the supply of provisions. A proclamation from King William exacerbated this situation. It instructed English plantations in the Americas and the Indies not to supply the Scottish settlement. As the Scottish ships arrived in Caledonia, Richard Long, a captain with the King’s Commission, planted the English flag in the Gulph of Darien. He declared,

‘I am not a hater of the Scots nation … but what I have done I thought it my duty to do for my master as they thought to do for theirs.'

The Spanish treatment of the unfortunate crew of the Dolphin exemplifies this confusion. The crew were incarcerated in Cartagena, then shipped back to Spain. They were then found guilty of invading Spanish territories in America. This was a contravention of King William’s orders and a treasonable offence. Even as this was happening, the Company of Scotland’s officers in Edinburgh wrote to the Council of Caledonia in April 1699. They hoped for the King’s protection, and that

‘the Government of England will now find it their interest also to be friendly to us in the maintenance of your said settlement against the attempts of any foreign enemies... the honour and interest of this Kingdom being now so firmly and inseparably linked with that of your Colony, you may depend upon our supplying you with ships, stores, men, arms provisions.'

Three ships were promised as help, but it was to prove too little, and too late.

Consequences of failure, and the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707

The failure of the Darien Scheme has been cited as one of the key reasons why, despite their misgivings, the Scots accepted the Act of Union of 1707. Many in the Scottish political classes realised that if Scotland was to become a major trading power, future commercial development could only be realised with unimpeded access to England’s colonies. It also required free trade between the two neighbouring nations.

The 'Darien Fiasco' caused severe damage to the Scottish economy. Many who invested in the Company of Scotland lost money. Scotland petitioned Westminster to compensate investors for these losses. Significantly, these investors included many people with political influence. As a result, the negotiations over Union included a clause granting an 'equivalent' of £398,085 10s to Scotland. This was partly to offset future liability towards the English national debt, and as personal compensation. This financial aid helped to secure support for the Act of Union of 1707 in the Scottish parliament. The opposition of many to the Union found voice in Robert Burns’ poem of 1791 ending with the lines,

'We're bought and sold for English gold - Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!'

Learn more about the Darien Scheme and its connection to Scotland and the Transatlantic slave system. The Darien chest is on display in the Kingdom of Scots Gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.