Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

A weaving loom collected by David Livingstone among the Mang’anja people in Mozambique or Malawi reveals fascinating links between past and present.

Date

Mid 19th century

Made in

Mozambique or Malawi

Made by

Mang’anja people

Made from

Wood, cane, textile

Acquired

By Dr David Livingstone and presented to the museum in 1861

Museum reference

On display

Discoveries, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

Livingstone donated many African objects to the Museum, including a grinding stone for preparing corn, geological specimens, fuel wood from the steamer used on one of his expeditions, a net for catching antelope and part of a hippo’s jaw.

This loom is made of a number of equal lengths of wooden sticks with a length of unfinished cotton cloth attached between them. It’s a peculiar looking object, really just a bundle of sticks and cotton thread, but in the hands of a skilled weaver, it’s a source of creativity and, importantly, once a source of income.

Above: Weaving loom collected by Livingstone among the Mang’anja people in Mozambique or Malawi.

The loom entered the collections in 1861, presented to the museum, according to the Annual Report for that year, by ‘Rev. Dr. David Livingstone’ from ‘Mang’anja country’.

This was one of a number of objects sent as a result of Livingstone’s friendship with Dr George Wilson, who had been appointed Director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland in 1855. They had met in 1838, in the chemistry laboratory of Thomas Graham at University College London, whilst Livingstone was a student and Wilson a demonstrator.

A small collection of objects from Livingstone arrived for the museum from 1858. These included geological specimens and objects demonstrating local resources, technologies and the potential for commercial enterprise, one of the key motivations for his exploration.

Above: Samples of gold and coal which Livingstone sent back to his friend Dr George Wilson.

Coming from a background dominated by the cotton weaving industry on the banks of the River Clyde, Livingstone would have had a particular interest in the production of cotton and local weaving technology. From the age of ten until he joined the London Missionary Society in 1838, Livingstone worked in Blantyre Mill, first as a ‘piecer’, tying together the broken threads between the spinning jennies, and later as a cotton spinner.

Livingstone described and illustrated the use of this type of loom in his book Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries. The work indicates how important cotton growing and weaving were for the Mang’anja people at the time of Livingstone’s travels, in the area around the Shire River in southern Malawi.

Southern Malawi continues to be a large cotton growing region. Museums of Malawi have been instrumental in setting up a new project at the Tisunge! Heritage Centre in the Shire River Valley, to reintroduce cotton weaving amongst the local people to provide a source of income, reviving weaving traditions that Livingstone had documented over 150 years ago.

Above: Tisunge! Heritage Centre in Chikwawa, Malawi.

In April 2012, Dr Sarah Worden, Curator of African Collections at National Museums Scotland, spent three weeks in Malawi, working with staff from Museums of Malawi. During her visit, she travelled to Chikwawa, an area dominated by cotton fields, and took the opportunity to collect contemporary cotton weaving and equipment to add to our museum collections. Through this fieldwork we have increased our knowledge of our existing collection, and Livingstone’s loom has been given a new contemporary relevance and link with the present in Malawi.

Above: Weaver Hendrix Lossan at Tisunge! Heritage Centre, Chikwawa, Malawi.

The loom is proof that, even though an object might seem a little unassuming at first, with research, fascinating links with the past and the present can be revealed.

Livingstone donated many African objects to our collections. The slideshow below shows a selection.

Glass slide depicting the exterior of Livingstone's birthplace, one of a set of 49 slides entitled The Life and Work of David Livingstone, published by the London Missionary Society c.1900.

David Livingstone was born into a hard working family in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, on 19 March 1813. The second child of seven, at the age of 10 he started work in a local cotton mill as a piecer, tying together broken threads on the looms. But despite a gruelling 14-hour day, he persisted with his studies, inspired and encouraged by his father, a Sunday School teacher.

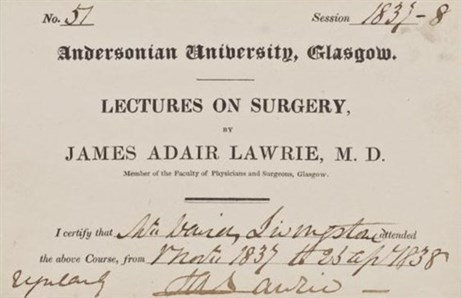

By 1836 he had saved enough money to study medicine at Anderson’s College in Glasgow, but he left two years later to train as a missionary with the London Missionary Society. After completing his medical studies in various hospitals around the capital, he eventually graduated in 1840. By December of the same year, ordained as a missionary, he set sail for Cape Town, South Africa.

Above: Livingstone's surgery certificate from Andersonian University. Courtesy of the National Trust for Scotland: David Livingstone Centre.

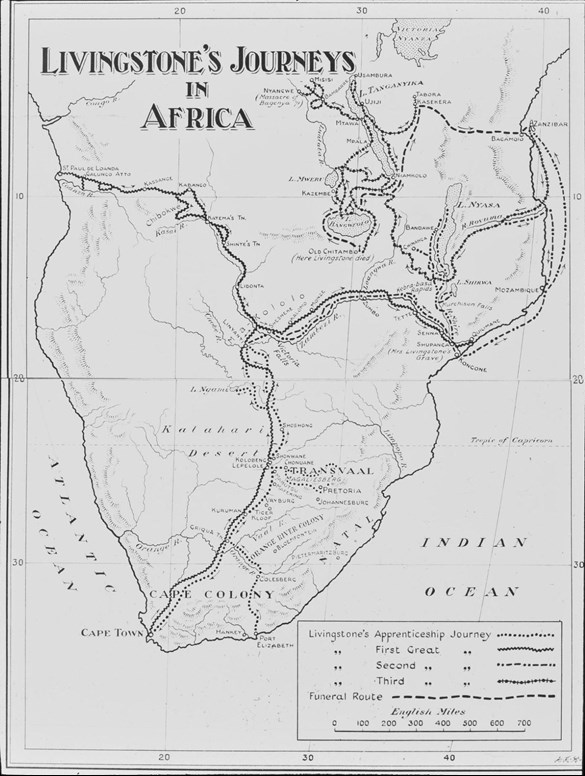

Livingstone’s mission was to spread the message not only of Christianity but of commerce too. He believed that establishing routes for legitimate trade would aid the abolition of the African slave trade, which he described as ‘this open sore upon the world’. This conviction inspired his first exploratory journeys northwards from modern-day Botswana, where he was based, through the Kalahari Desert. It was during this period that he was famously attacked and mauled by a lion, causing permanent damage to his left arm.

Between 1852 and 1856 he followed the Zambezi River, intent on finding routes from the coast to the interior of Africa that could be used by missionaries and traders. In 1855 he became the first European to reach the spectacular Mosi-oa-Tunya (‘the smoke that thunders’) waterfall, which he renamed Victoria Falls in honour of his Queen. By 1856 he had reached the mouth of the Zambezi at the Indian Ocean, making him the first European to cross central southern Africa from west to east.

That same year Livingstone returned to Britain, where he published his best-selling book, Mission travels and researches in South Africa, which made him a famous and popular public figure.

In 1858 Livingstone returned to South Africa with his wife Mary, whom he had married in 1854 and with whom he had six children. Mary was the daughter of Dr Robert Moffat, the missionary who had first inspired the newly-qualified medic to go to Africa.

Funded by the British Government, Livingstone aimed to navigate the River Zambezi to find a passable trade route, but cataracts and rapids made passage impossible by boat. The beleaguered doctor was dealt another blow when, in 1862, Mary Livingstone contracted malaria and died.

Gruelling, expensive and fraught with disease and disputes, the Zambezi expedition was deemed a failure by the British Government, who cancelled it in 1864. However, Livingstone notched up another first for European exploration when he reached Lake Nyassa, now known as Lake Malawi, the eighth-largest lake in the world, which he explored by paddle steamer sent over from England.

Above: Map showing Livingstone's journeys.

Livingstone found it difficult to secure funding for further exploration but in 1866 he set sail for Africa again, this time to search for the source of the Nile. The expedition was to prove too much. Cut off from the Western world, plagued by ill-health, deserted by many of his assistants and with most of his supplies stolen, he was forced to accept help from slave traders in the area, despite being utterly sickened by their activities.

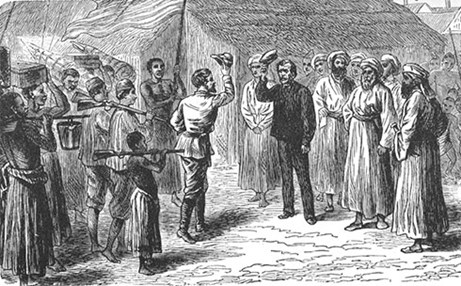

In 1871, ill and despondent, he abandoned his search and returned to the town of Ujiji in Tanzania, where he was eventually tracked down by the journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who had been sent to find him by the New York Herald newspaper. Stanley allegedly greeted him with the now famous words, ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’

Above: Dr Livingstone, I presume? Illustration from the French edition of Henry Morton Stanley's How I Found Livingstone, Comment J'ai Retrouvé Livingstone, 1876.

With replenished supplies courtesy of Stanley, Livingstone resumed his quest. But in May 1873 he died from malaria and dysentery in the village of Chief Chitambo in Zambia.

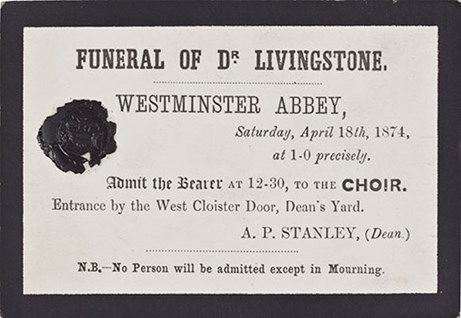

Livingstone’s loyal servants, freed slaves Chuma and Susi, buried his heart beneath a tree in the village, then carried his embalmed body over a thousand miles to the coast of Tanzania, where it was transported by ship to England. This act of devotion, together with Stanley’s glowing report, helped transform his tarnished reputation from failed expedition leader to national hero, and the relentless explorer was finally laid to rest with full honours in Westminster Abbey on 24 April 1874.

Above: Invitation to Livingstone's funeral at Westminster Abbey. Courtesy of the National Trust for Scotland: David Livingstone Centre.

Livingstone spent 30 years in Africa. During that time he travelled over 46,000km, mostly on foot, discovering previously unknown wonders and vastly increasing European knowledge of the geography of the continent. His passionate denouncement of slavery did much to incite support for its abolition, while the passages he navigated allowed missionaries to introduce new forms of health care and education, and traders to increase commerce.

To this day he is respected and loved in many of the areas he visited, particularly Malawi, which has retained strong connections with Scotland.

When Chitmabo’s people returned the explorer’s body to Britain, they sent with it a note that read: ‘You can have his body, but his heart belongs to Africa.’ How right they were.

Above: Carte-de-visite depicting Dr David Livingstone by Thomas Annan, Glasgow. Part of the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland.

In 2013, we celebrated the bicentenary of Livingstone’s birth with an exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, which brought a new focus to the man, the myth and his legacy. In this podcast, journalist Lee Randall talks to exhibition curator Dr Sarah Worden and Lovemore Mazibuko, Acting Director Museums of Malawi, Chichiri, to find out more about Livingstone’s life and how he is remembered today.